Nearly half of nationals say it is okay for people to express their ideas on the internet even if they are unpopular (48%) and that people should be free to criticize government online (46%). Fewer—four in 10—feel it is safe to say whatever one thinks about politics on the internet.

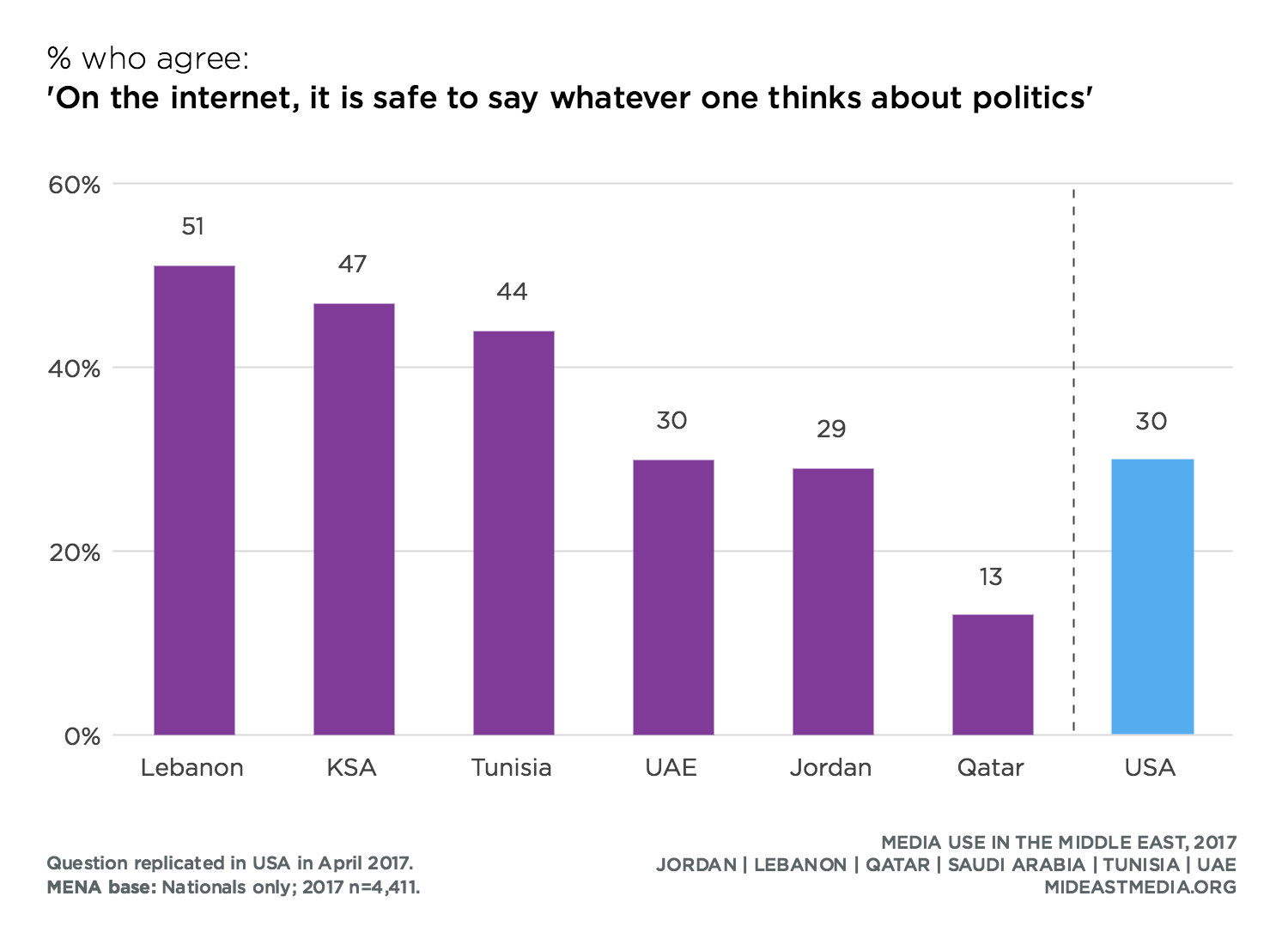

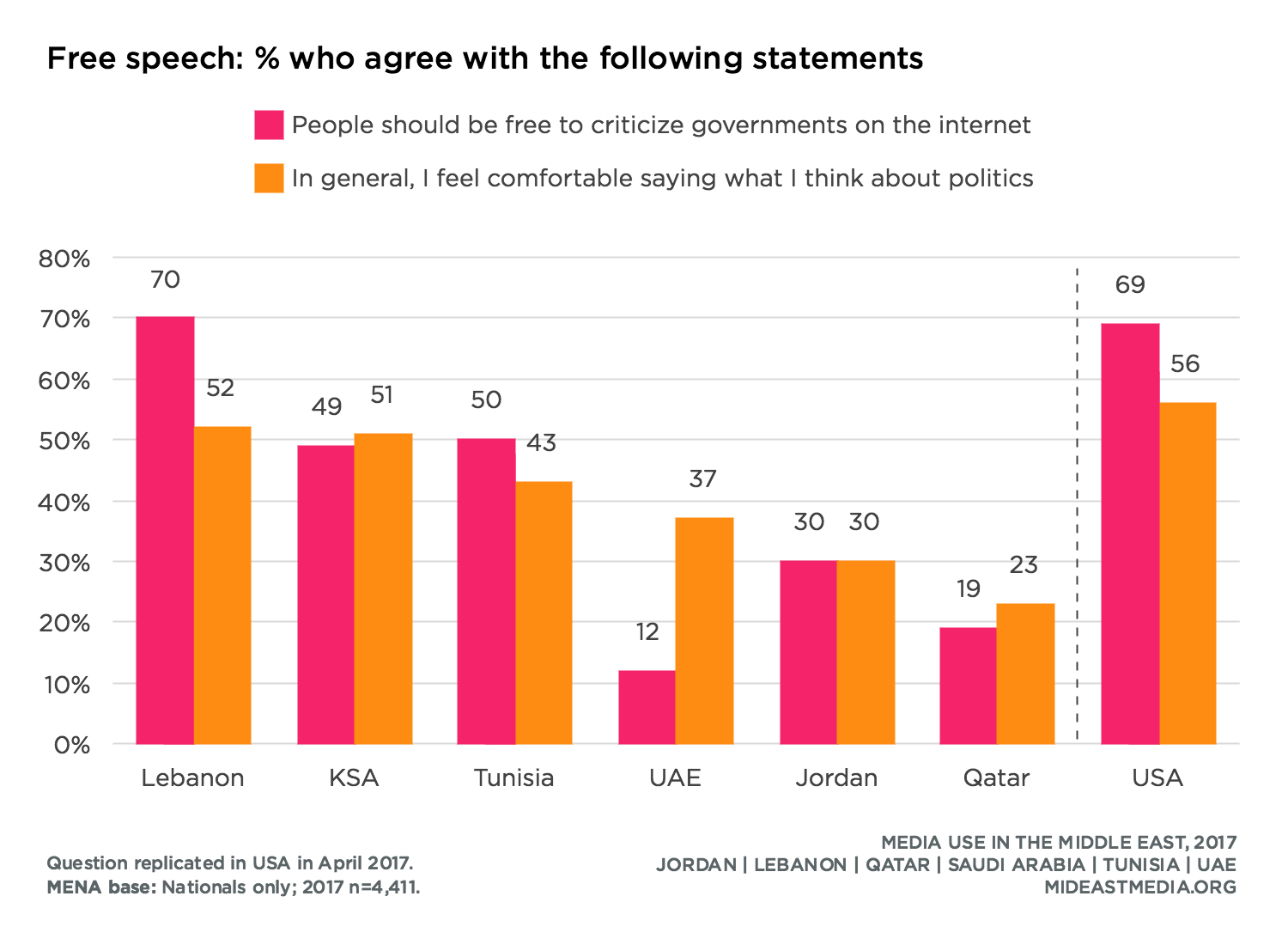

Opinions about free speech online—what people should be able to say versus what they can safely say—vary widely by country. In Lebanon, for example, far more nationals believe people should be able to criticize government online as feel it is safe to say what one thinks about politics online (70% okay to criticize government online vs. 51% safe to express political opinions online), while Emiratis are twice as likely to say it is safe to talk about politics online than to agree people should be able to criticize government online (12% okay to criticize government online vs. 30% safe to express political opinions online). Qataris are less likely than most other nationals to agree with either statement (19% okay to criticize government online, 13% safe to express political opinions online).

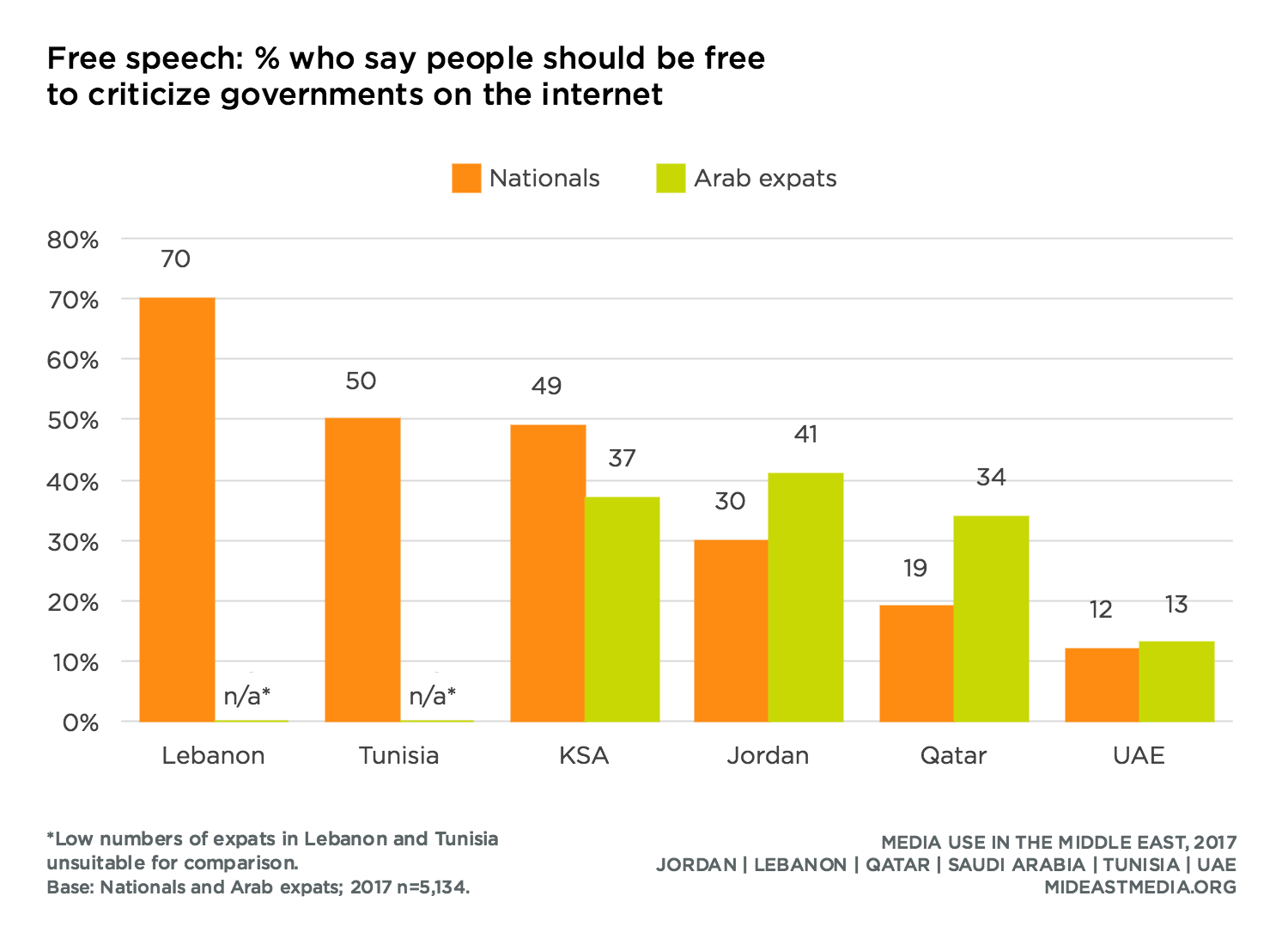

More Western expatriates than other groups in the region say it is okay to express unpopular ideas online (56% Western expats vs. 49% Asian expats, 44% Arab expats, 48% Nationals). In contrast, more nationals feel citizens should be able to criticize government online, by seven to 16 percentage points across groups (46% Nationals vs. 30% Arab expats, 39% Asian expats, 38% Western expats). Nationals and Western expatriates are more likely than Arab and Asian expatriates to say they feel safe discussing politics online (42% Western expats, 40% Nationals vs. 34% Asian expats, 30% Arab expats).

More Americans than Arab nationals say people should be able to criticize government online---by 23 percentage points (46% Middle East vs. 69% U.S.; U.S. data: Harris Poll, 2017). However, fewer Americans say it is safe to express political opinions online (40% Middle East vs. 30% U.S.; U.S. data: Harris Poll, 2017). Lebanese are more similar to Americans than other Arab nationals in the belief that people should be able to criticize government online, with seven in 10 in in agreement.

Across the region, those with the lowest education (primary or less) are the least likely to agree people should be able to express unpopular ideas, criticize government, or speak their minds about politics online—by about 20 percentage points compared to those with more education (express unpopular ideas online: 28% primary or less vs. 47% intermediate, 51% secondary, 51% university or higher; criticize government online: 24% vs. 46%, 49%, 50%, respectively; safe to express political opinions online: 20% vs. 38%, 43%, 43%, respectively).

Fewer of the oldest nationals agree people should be able to express unpopular ideas, criticize government, or speak their minds about politics online—by 10 to 15 percentage points compared to their younger counterparts (express unpopular ideas online: 53% 18-24 year-olds, 50% 25-34 year-olds, 48% 35-44 year-olds, 38% 45+ year-olds; okay to criticize government online: 49%, 49%, 49%, 39%, respectively; safe to express political opinions online: 44%, 42%, 43%, 32%, respectively).

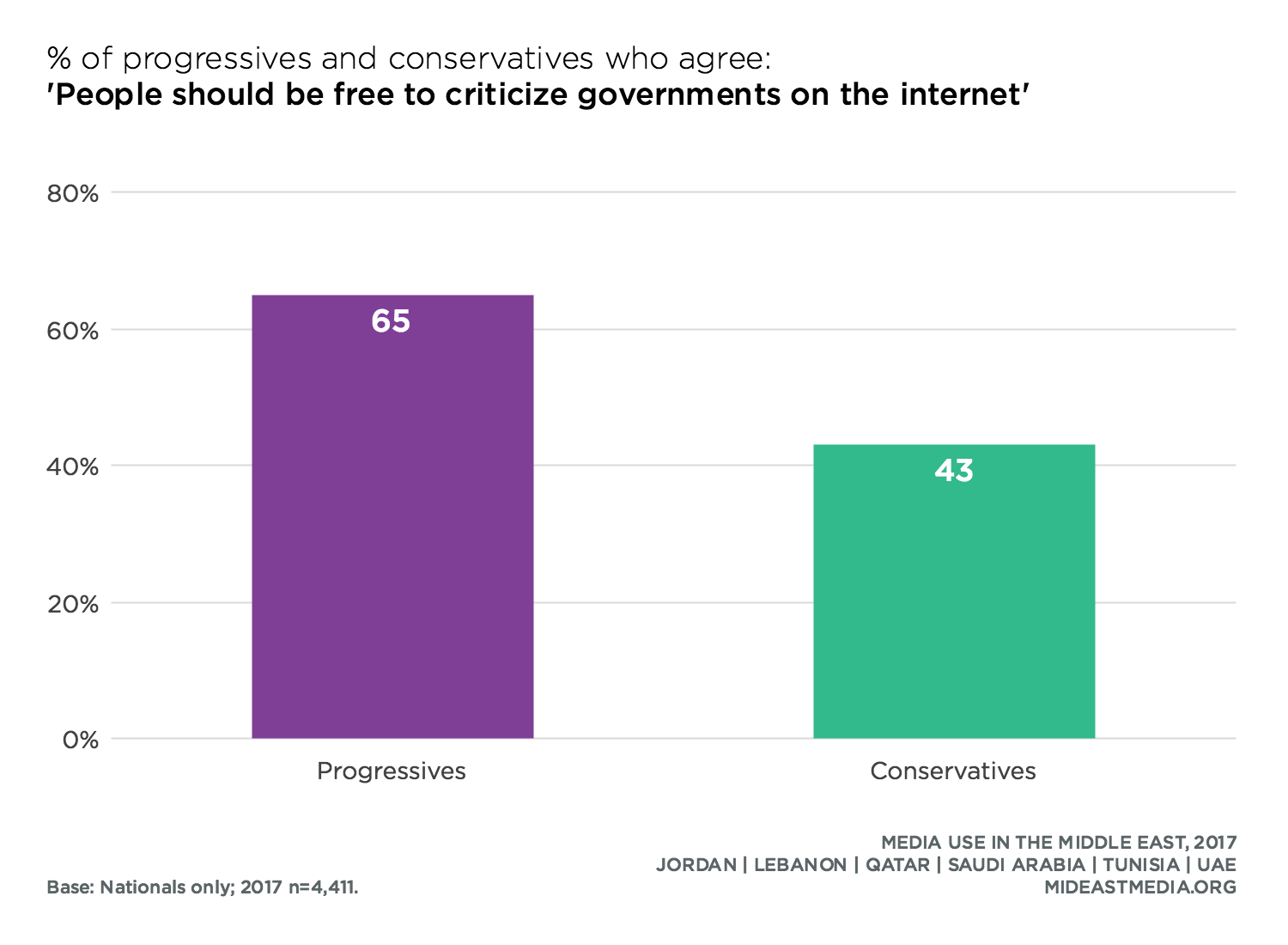

Nationals who describe themselves as progressive rather than conservative align with greater online speech freedoms for these same questions (expressing unpopular ideas online: 55% progressive vs. 46% conservative; safe to express political opinions online: 47% progressive vs. 40% conservative). Even more progressives than conservatives say it is okay to criticize government online—a difference of more than 20 percentage points.

Additionally, more of those who say their country is off on the wrong track support online freedom of speech by about 10 percentage points compared to those who feel their nation is headed in the right direction. More than or nearly half who say their country is off on the wrong track also say it is okay for people to express unpopular ideas online and that such expression is safe (express unpopular ideas online: 57% wrong track vs. 45% right direction; safe to express political opinions online: 47% wrong track vs. 38% right direction). The greatest difference between these groups concerns support for criticizing government online, growing to a nearly 20-point difference between nationals feeling their country is off on the wrong track versus headed in the right direction.

More than twice as many nationals who agree that they feel comfortable speaking about politics support the right to criticize government online compared to those who disagree (okay to criticize governments: 71% agree they feel comfortable discussing politics online vs. 31% disagree). Similarly, among nationals worried about governments checking what they do online, nearly three-quarters support the right to criticize government online—double the proportion who are not concerned about government surveilling their online activity.

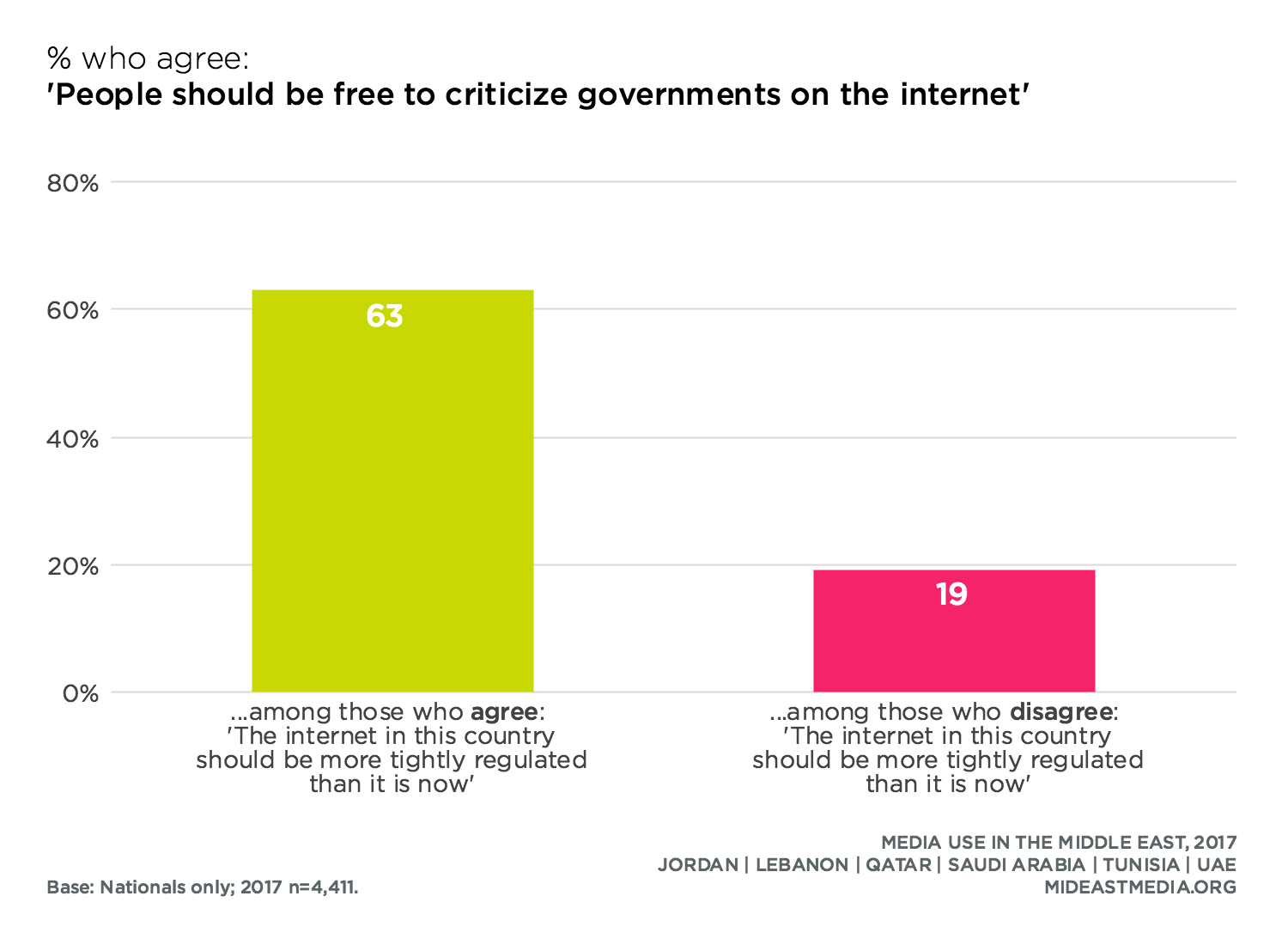

Nationals who want more internet regulation in their country are three times more likely than those who do not support more regulation to say people should be able to criticize government online.

Respondents who say the internet affords them greater political efficacy are also more likely to support online freedom of speech than those who do not see the internet as increasing political influence. They are more likely to say it is okay to express unpopular ideas online (60% agree they can have political influence online vs. 45% disagree), to say people should be able to criticize government online (60% vs. 44%), and to feel it is safe to express political opinions online (55% a vs. 35%).

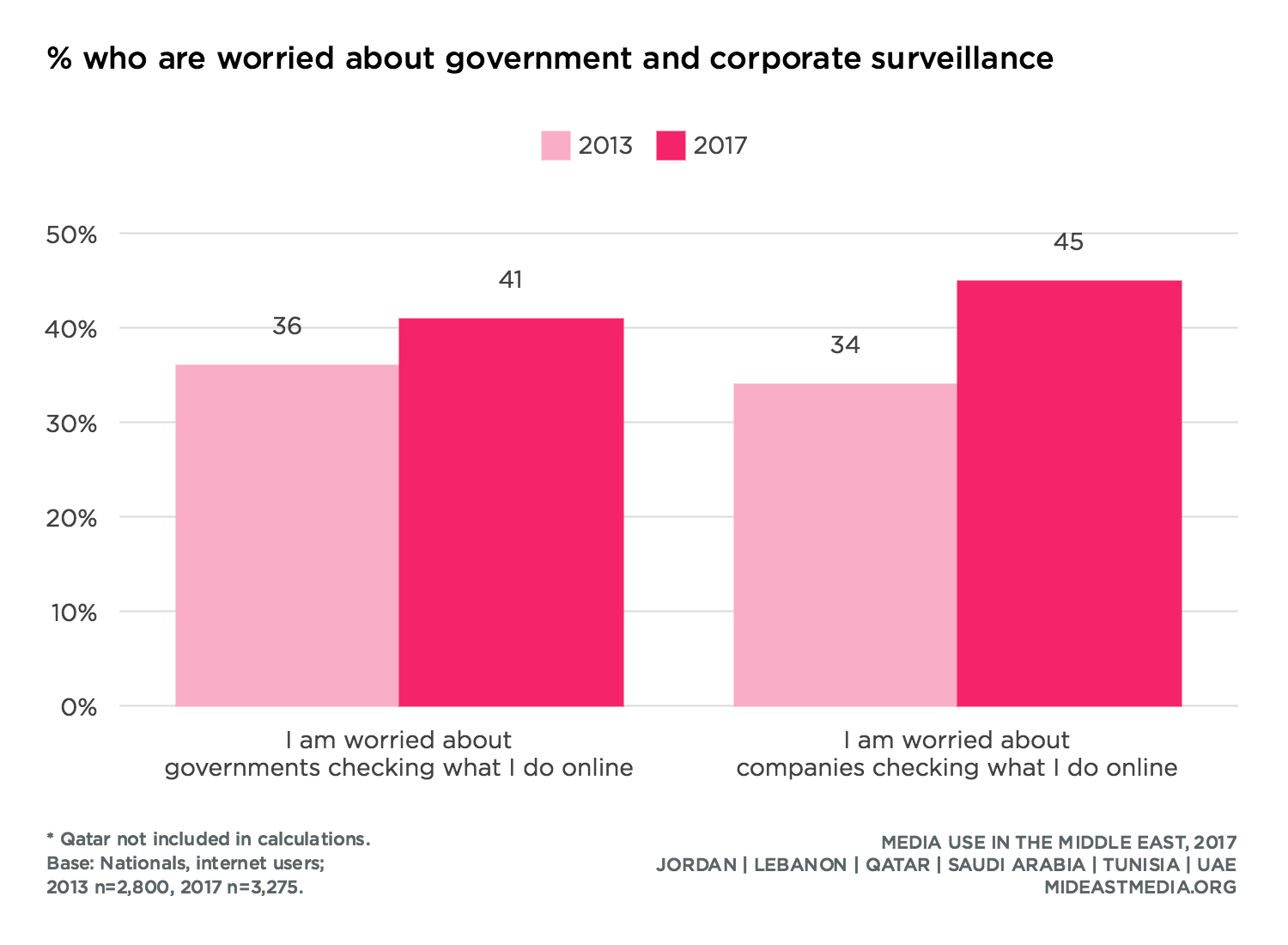

About four in 10 internet users are concerned about either governments or companies monitoring what they do online. While fear of government surveillance is up only a few percentage points since 2013, there has been a significant increase (11 percentage points) in concern about being monitored by companies.

Across nations, the lowest levels of concern were reported by internet users in Qatar and the UAE, where fewer than 20% worry about governments and only 20% to 25% worry about companies monitoring their online activity, compared to the highest rates—around 50%—concerned about surveillance by both governments and companies in Saudi Arabia and Tunisia.

While younger nationals are more likely to support free speech online, higher percentages of younger nationals also express concerns about online monitoring by governments and companies (governments: 27% 45+ year-olds vs. 35% 18-24 year-olds, 39% 25-34 year-olds, 38% 35-44 year-olds; companies: 28% vs. 41%, 43%, 42%, respectively).

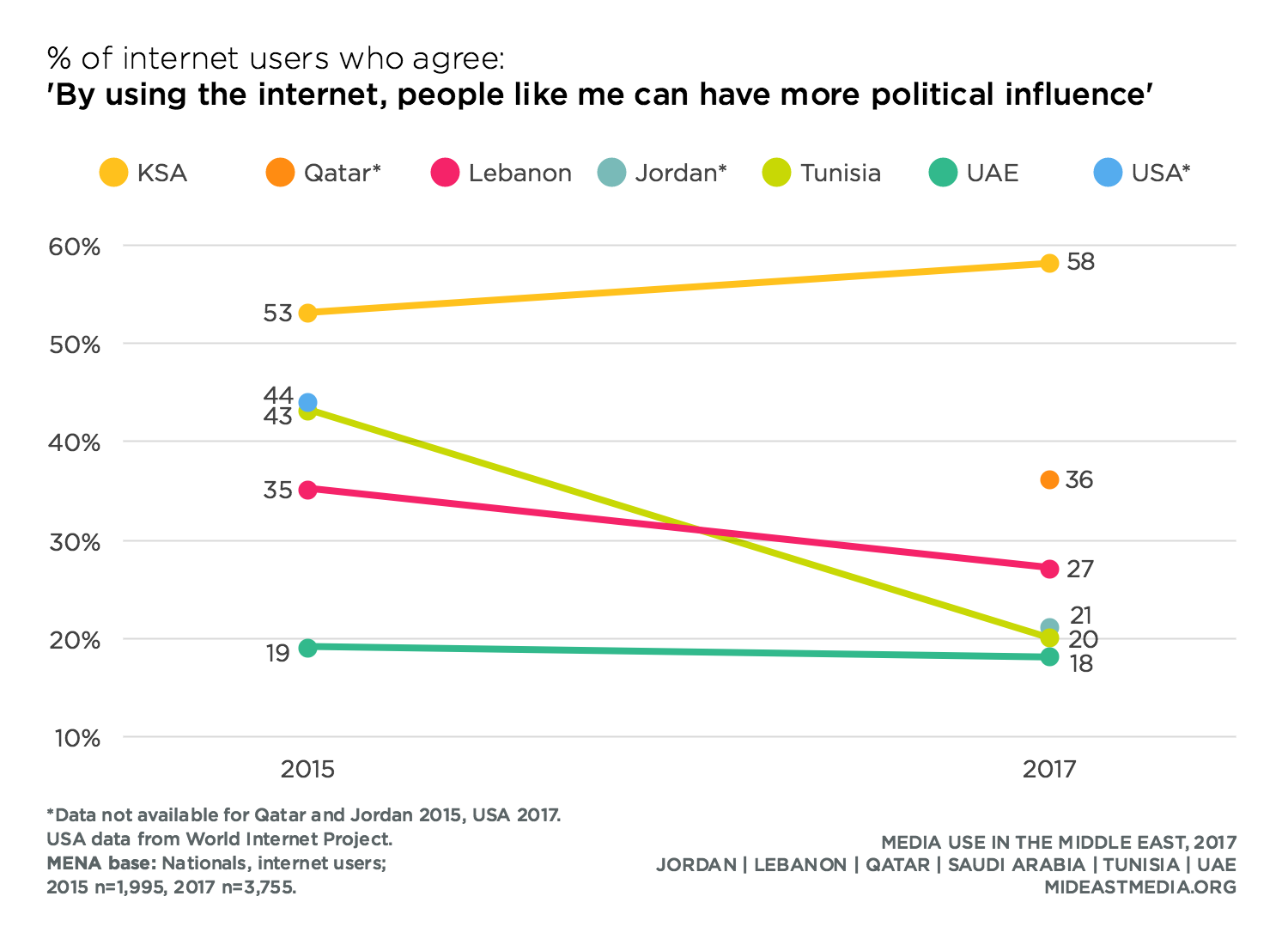

Three in 10 internet users believe they can have more political influence by being online. Internet users in Saudi Arabia and Qatar are the most likely to feel they can have influence (58% KSA, 36% Qatar vs. 18% UAE, 21% Jordan, 21% Lebanon, 20% Tunisia). This represents a sharp decline from 2013 in perceptions of political influence online in Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia, and the UAE (Jordan: 26 percentage point drop; Lebanon: 10-point drop; UAE: 18-point drop).

Among internet users, Western and Asian expatriates are more likely than Arabs to feel they can have more political influence by being online (39% Asian expats, 45% Western expats vs. 30% Nationals, 29% Arab expats).

The proportion of nationals who feel they can have political influence on the internet varies little by age but rises with education (17% primary or less, 21% intermediate, 31% secondary, 33% university or higher).

Nationals who see their country heading in the right direction are more likely to see greater political efficacy in the internet (34% right direction vs. 22% wrong track).

Arab nationals who agree with free speech online and feel comfortable discussing politics online are also more likely to feel they can have political influence by using the internet (can have more political influence online: 34% agree it is okay to express ideas on the internet vs. 19% disagree; 38% agree they feel comfortable discussing politics vs. 19% disagree).

Overall, support for internet regulation is on the rise, up seven percentage points since 2013 (53% in 2013 vs. 60% in 2017). This rise across the Middle East reflects increases in Jordan, Lebanon, and the UAE (Jordan: 43% in 2013 vs. 57% in 2017; Lebanon: 63% vs. 77%; UAE: 29% vs. 41%). Otherwise, support for tighter internet regulation stayed roughly the same in Saudi Arabia and Tunisia and fell dramatically in Qatar (KSA: 59% in 2013 vs. 57% in 2017; Tunisia: 51% vs. 56%; Qatar: 60% vs. 39%).

Qatar and the UAE are the only nations where minorities of nationals favor greater internet regulation (39% Qatar, 41% UAE).

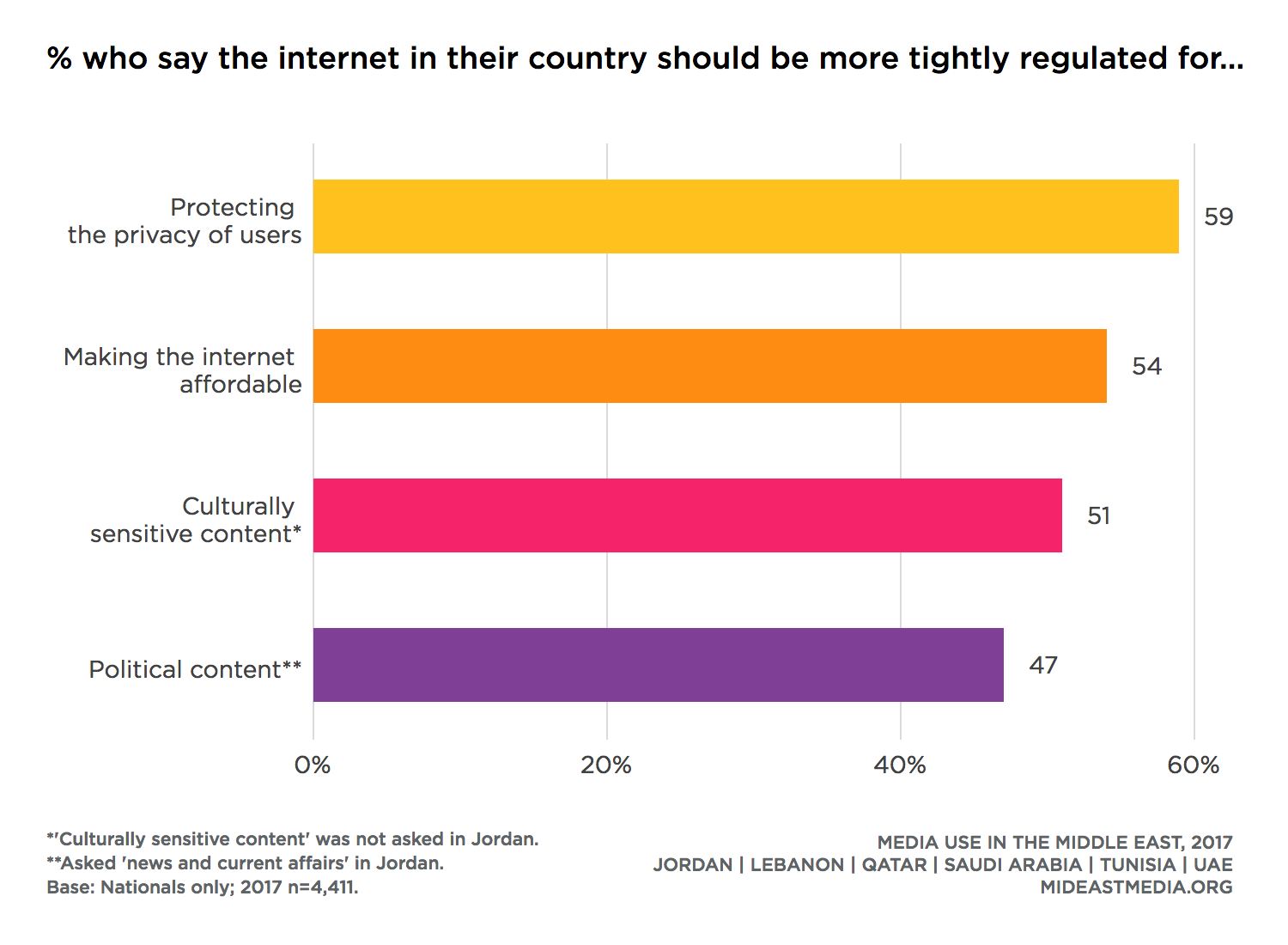

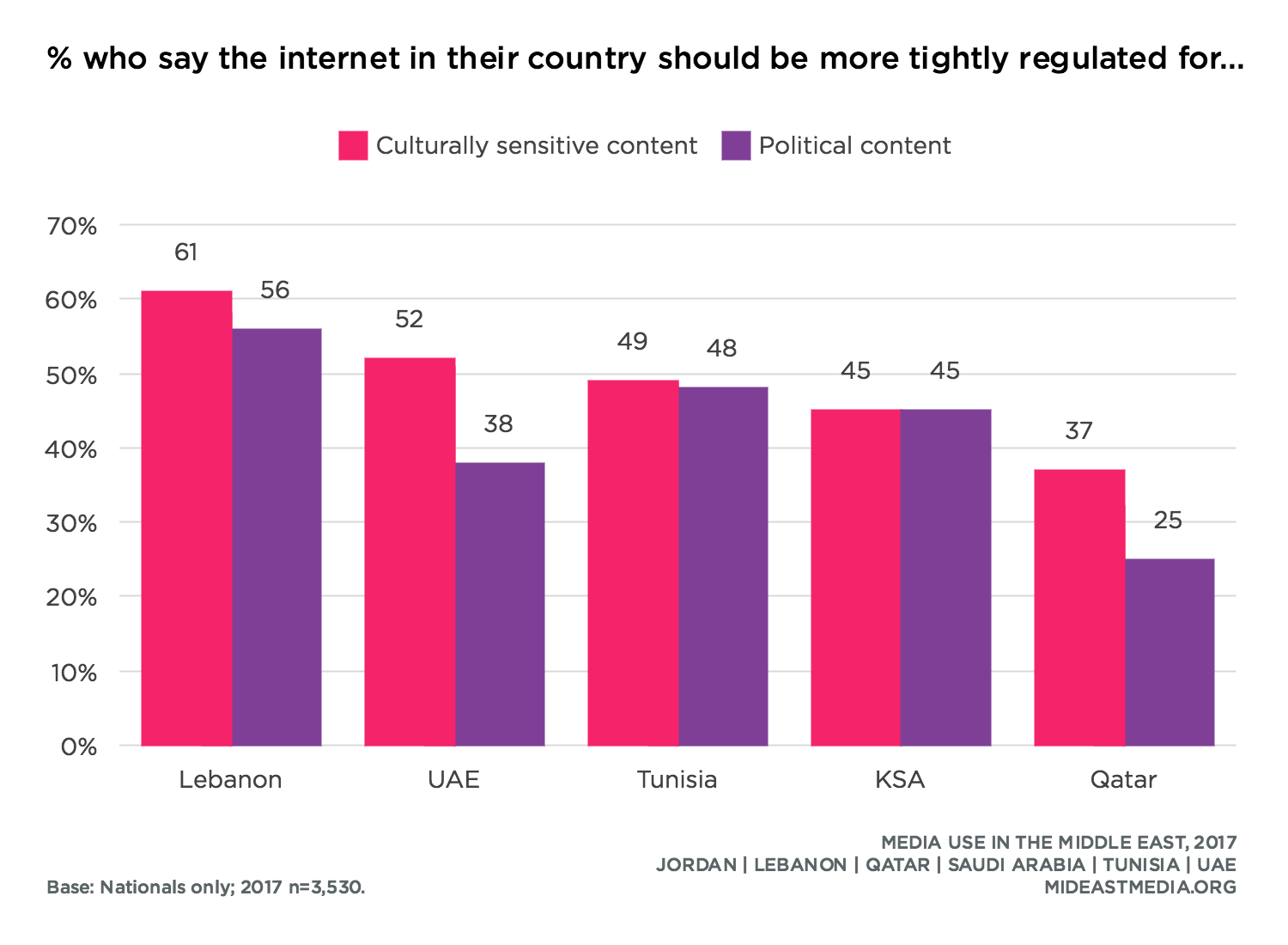

Roughly half of nationals support tighter internet regulation for political content, culturally sensitive content, and cost (making sure the internet is affordable), while close to six in 10 support tighter regulation to protect the privacy of online users.

Compared with other nationals, fewer Qataris support tighter internet regulation related to content (political and culturally sensitive), but they favor tighter regulation concerning privacy and affordability at rates similar the other nationals. Lebanese show the highest rates supporting tighter regulation, ranging from 56% for political content to over three-quarters for protecting user privacy and making the internet affordable (75% protecting user privacy, 78% making the internet affordable).

Compared to expatriate groups, more nationals favor a general increase in internet regulation (60% Nationals vs. 41% Arab expats, 36% Asian expats, 36% Western expats). However, the proportions supporting specific types of regulation (content, cost, and privacy) are more similar across nationalities, with Arab expatriates generally expressing the least support for the various forms of regulation.

Fewer of the least-educated internet users support internet regulation, by about 20 percentage points, compared to those with more than a primary education. Half of the least-educated group want more internet regulation compared to two-thirds of those with more education (51% primary or less vs. 69% intermediate, 65% secondary, 67% university or higher). Similarly, only one-third of the least-educated internet users support more regulation of political content, compared to half of those with more education (34% primary or less vs. 47% intermediate, 50% secondary, 54% university or higher).

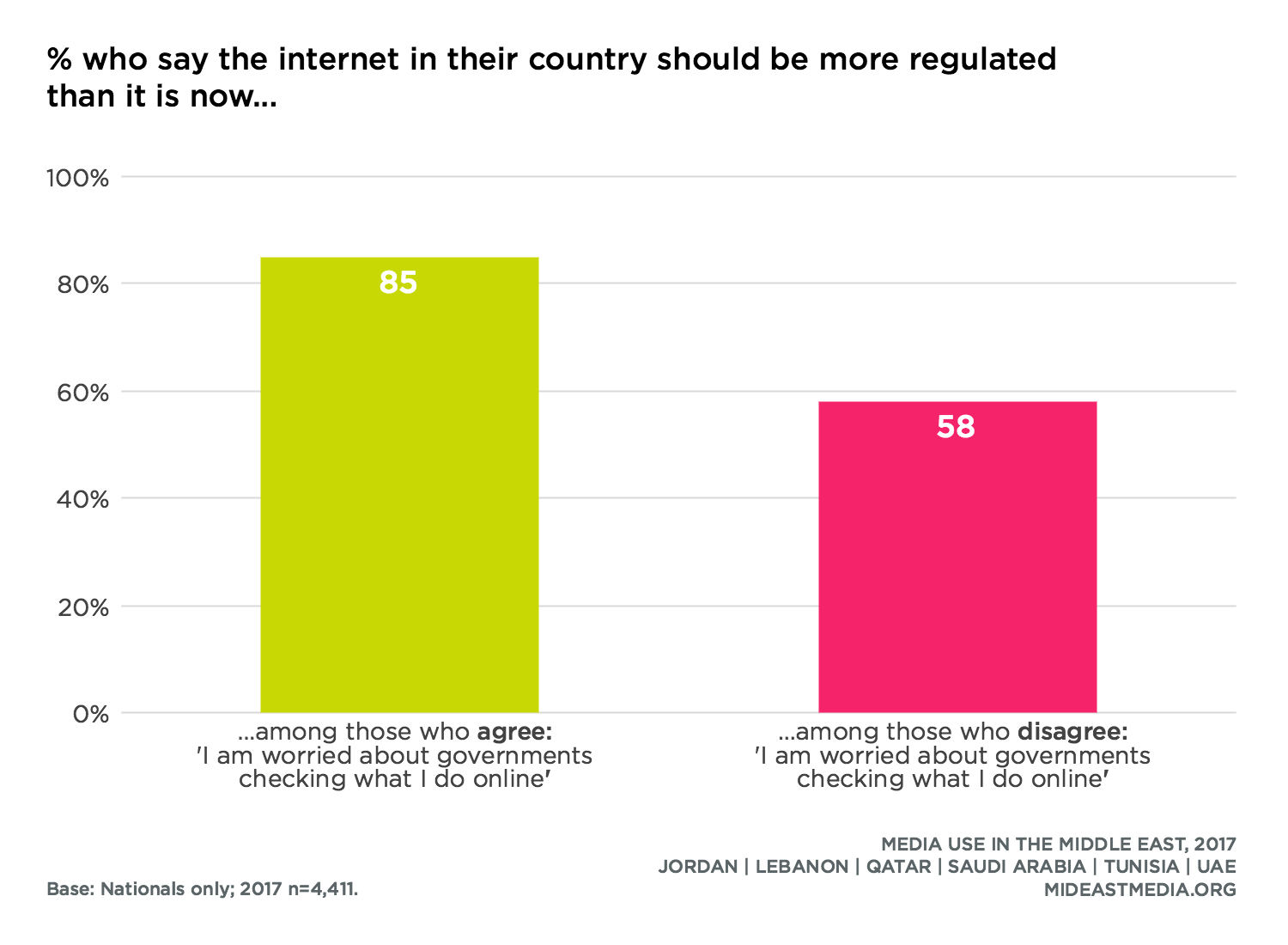

Respondents who worry about governments checking what they do online favor all forms of increased internet regulation in greater proportions than those who are not worried. This likely highlights their likely definition of “internet regulation” in terms of more online protections as opposed to favoring increased censorship or more restrictions of online speech (increase regulation to protect user privacy: 73% worry vs. 61% do not worry; increase regulation to make the internet affordable: 67% worry vs. 55% do not worry; increase regulation of political content: 63% worry vs. 44% do not worry; increase regulation of culturally sensitive content: 66% worry vs. 49% do not worry).

Support for increased regulation to protect user privacy and content is more common among those who agree that the internet affords more political influence online than those who disagree (support increased regulation to protect user privacy: 70% agree people have more political influence online vs. 60% disagree; for political content: 58% agree vs. 49% disagree; for culturally sensitive content: 62% agree vs. 51% disagree).

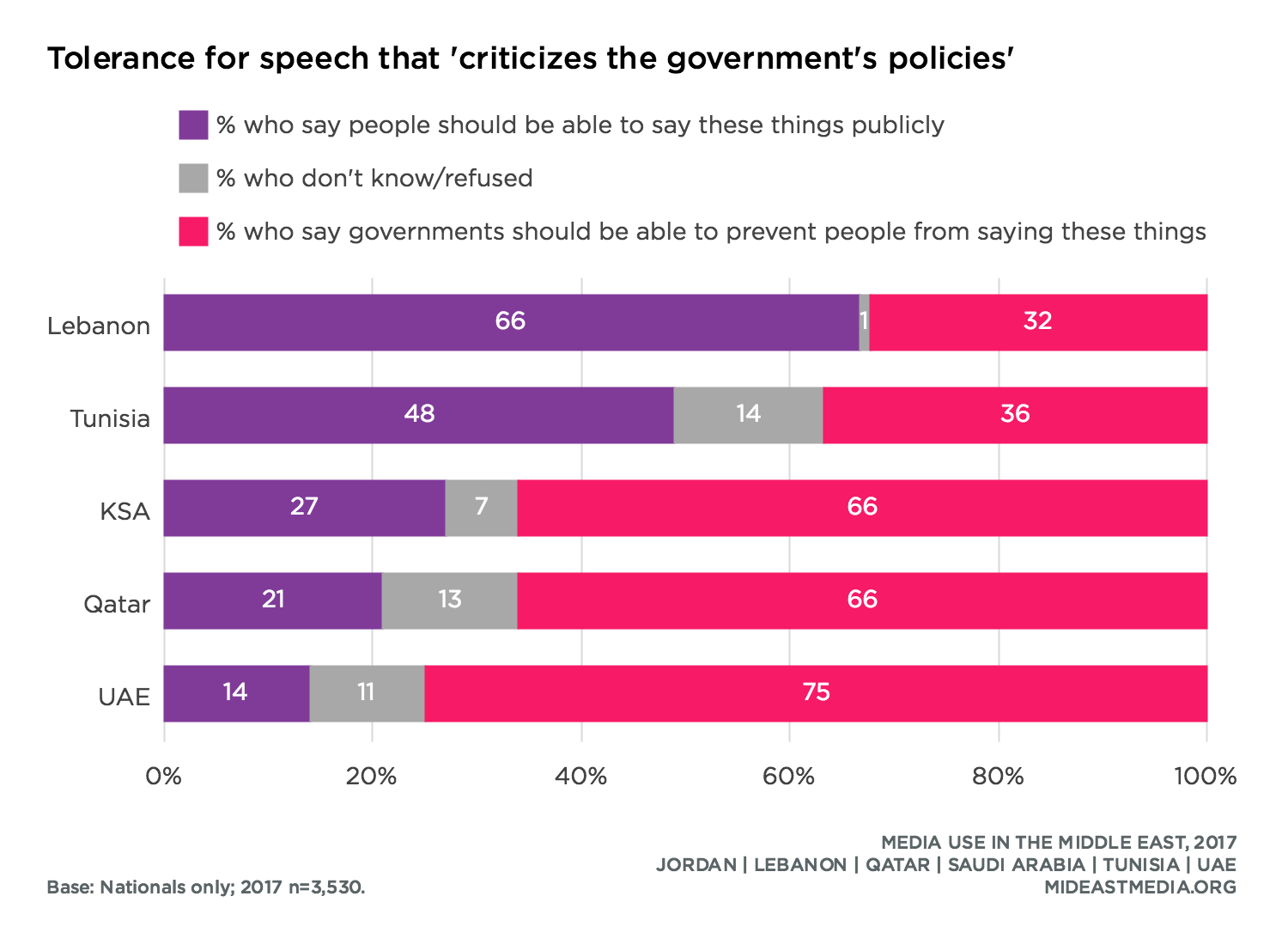

Respondents were asked if they think people should be able to speak publicly about various topics or if the government should be able to prevent people from speaking on these subjects. The topic areas included: statements that criticize the government’s policies, statements that are offensive to one’s religion or beliefs, and statements that are offensive to minority groups.

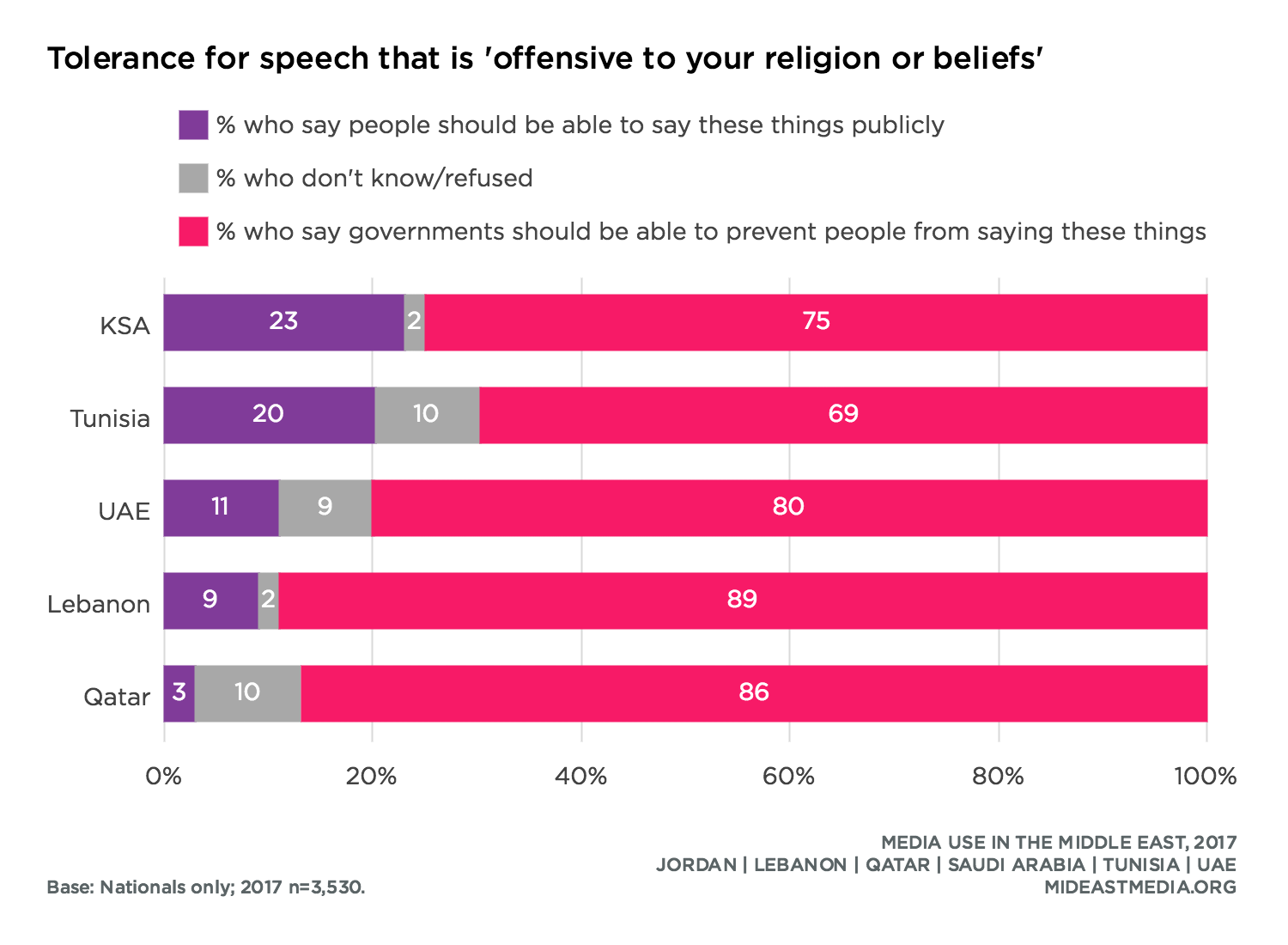

Three times as many nationals think people should be able to publicly criticize the government’s policies than should be allowed to make offensive statements about one’s religion and beliefs or about minorities. The large majority, over three-quarters of nationals, agrees the government should have the right to prevent free speech offensive to religion and minorities, as opposed to only about half who support official censorship of government policies.

Variations by country emerge. Two-thirds of Lebanese support a right to publicly criticize government policies and just one-third say the government has the right to prevent such critiques. Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and especially the UAE represent the opposite end of the spectrum, with about one-quarter of Qataris and Saudis and only 14% of Emiratis believing people should have the freedom to criticize government policies. Two-thirds of Qataris and Saudis and three-quarters of Emiratis think the government should be able to prevent public criticism.

Less than one in five nationals believe fellow citizens should be able to publicly offend others’ religion or beliefs, and three-quarters say government should be able to block such speech. Only a few more Saudis and Tunisians than other nationals are comfortable with public statements offensive to their religion, while less than one in 10 Lebanese and Qataris support such speech.

Similarly, a few more Saudis and Tunisians tolerate offensive speech about minorities than the regional average (should be able to make offensive statements: 25% KSA, 21% Tunisia vs. 17% regional average; government should prevent offensive statements: 72% KSA, 68% Tunisia vs. 77% regional average).

More nationals than expatriates support the freedom to criticize the government’s policies (44% Nationals vs. 31% Arab expats, 30% Asian expats, 34% Western expats). Arabs, both nationals and expatriates, are less likely than either Asian or Western expatriates to tolerate speech offensive to their religion or to minority groups (offensive speech is okay against religion or beliefs: 15% Nationals, 9% Arab expats vs. 25% Asian expats, 32% Western expats; against minority groups: 17% Nationals, 10% Arab expats vs. 22% Asian expats, 30% Western expats).

A significantly smaller portion of nationals with the least education support free speech against government policies compared to more educated respondents (35% primary or less vs. 50% intermediate, 43% secondary, 47% university or higher).

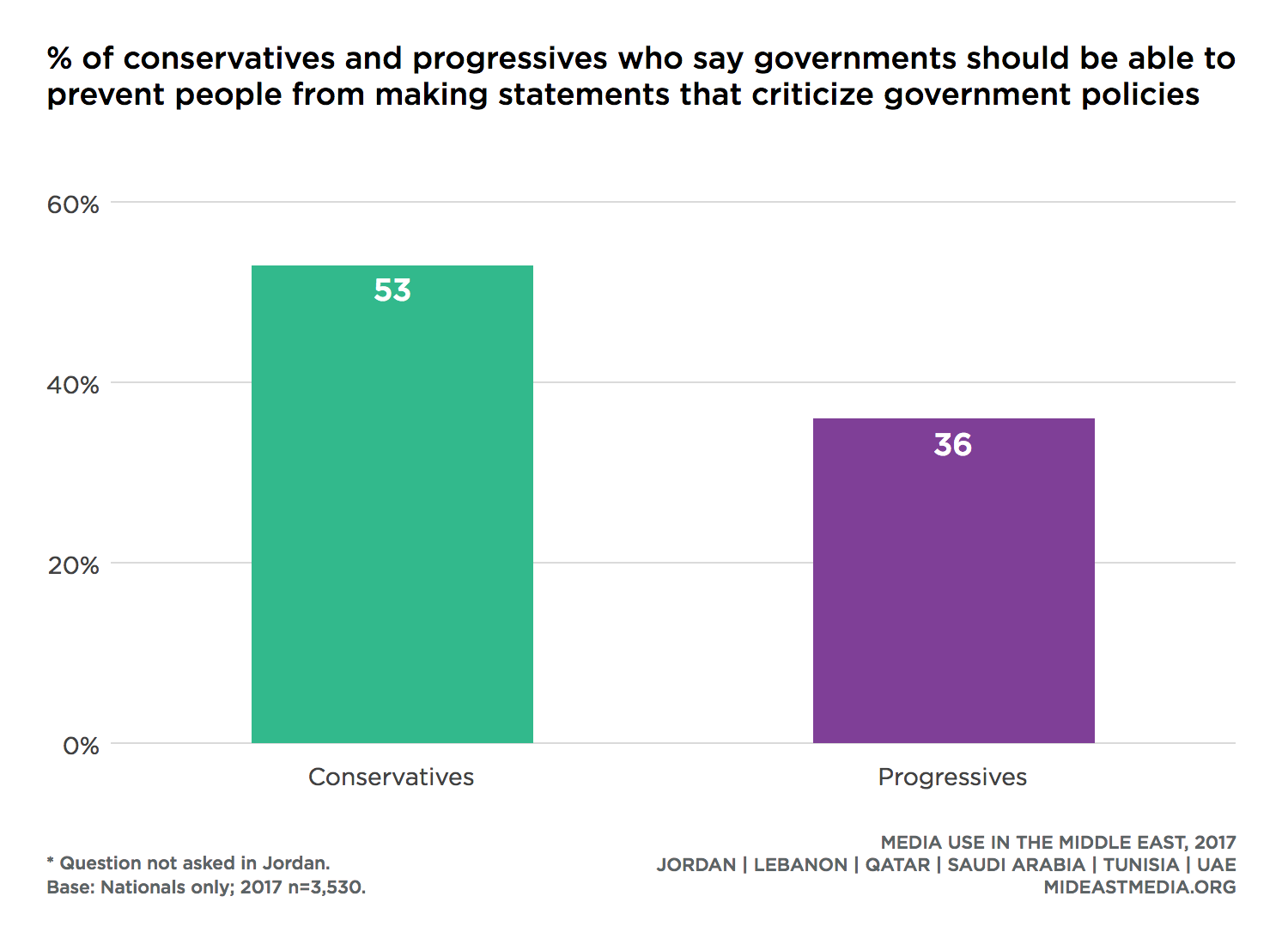

Self-identified progressives are more likely than conservatives to support the freedom to criticize government policies by nearly 20 percentage points; conservatives are more likely to feel government should be able to prevent such criticism.

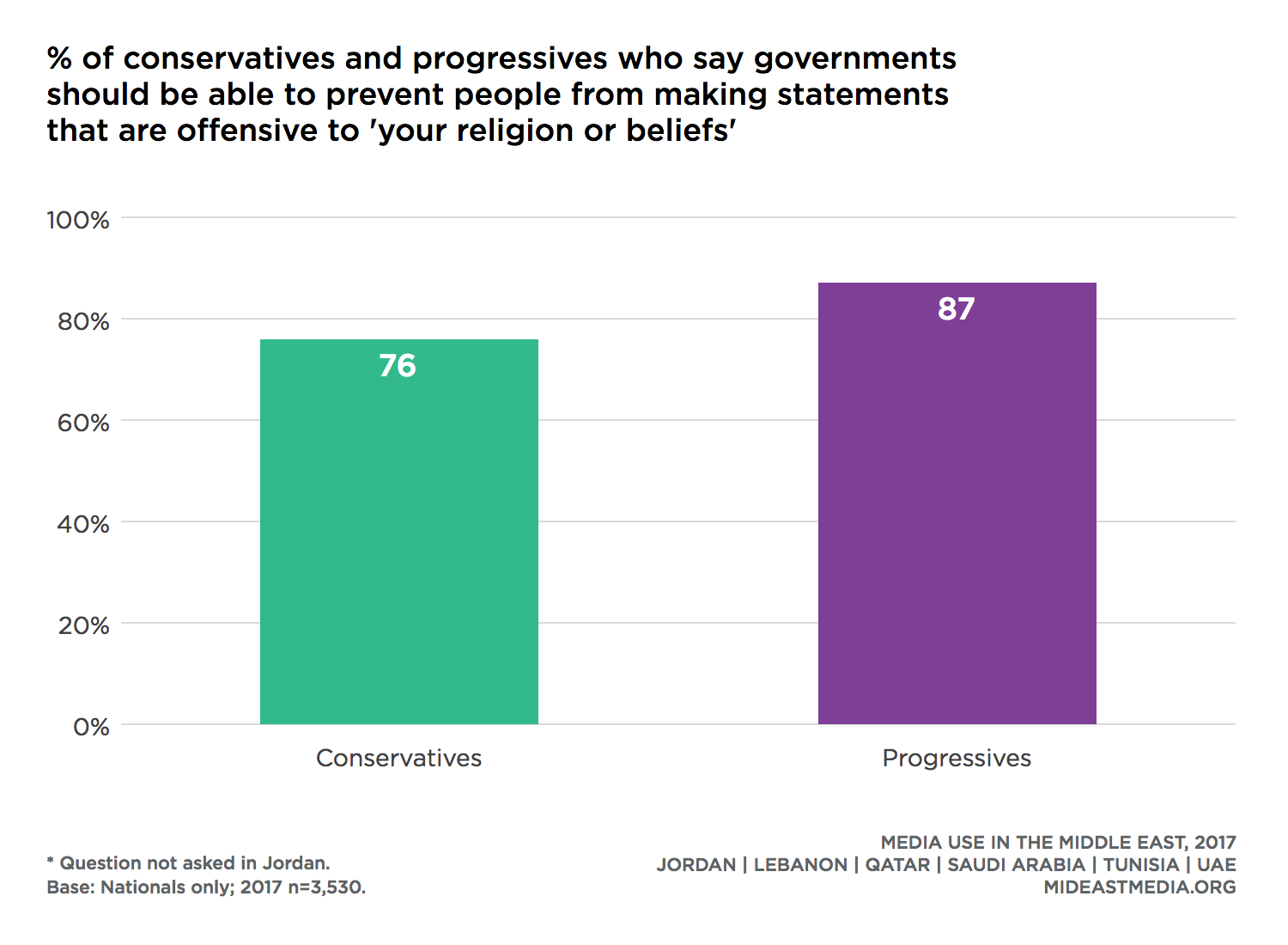

However, the reverse is true concerning speech offensive to one’s religion or to minorities, as only half as many progressives as conservatives support speech that offends religious beliefs. Large majorities of both progressives and conservatives support government prevention of statements offensive to one’s religion or to minorities, but progressives even more so than conservatives.

More nationals who say their country is off on the wrong track rather than headed in the right direction support the freedom to publicly criticize government policies (55% wrong track vs. 40% right direction).