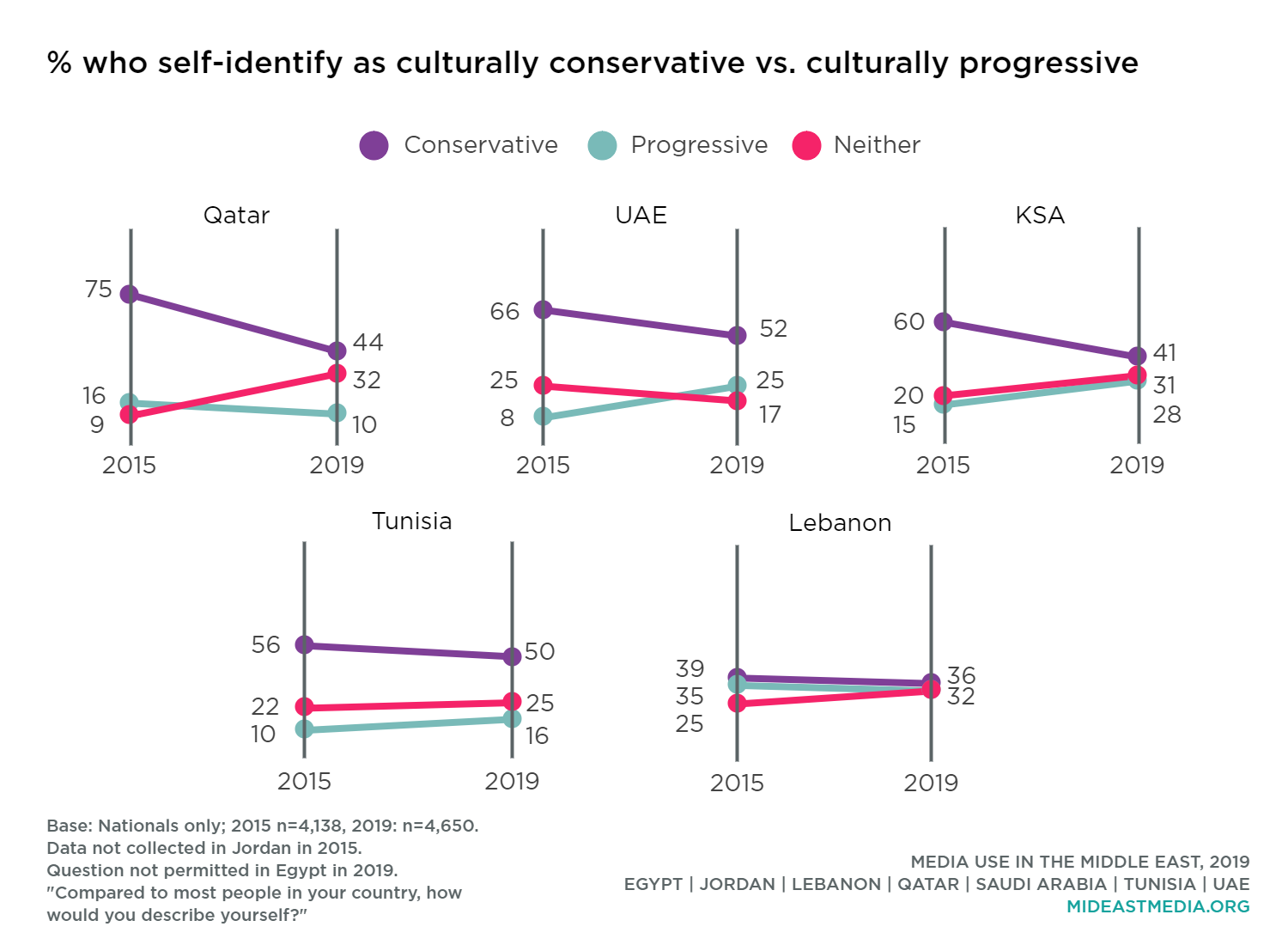

Cultural attitudes since 2015 seem to be converging in some countries. The portion of nationals in each country self-identifying as culturally conservative has decreased since 2015, especially in Qatar and Saudi Arabia—where it dropped 31 and 19 percentage points, respectively—and now fewer than half of Qataris and Saudis describe themselves as culturally conservative. Simultaneously, the portion identifying as culturally progressive rose in every country except Qatar, where the group choosing neither conservative nor progressive nearly quadrupled. Lebanon is evenly split on this measure; one-third of Lebanese self-identify with each conservative, progressive, and neutral attitudes.

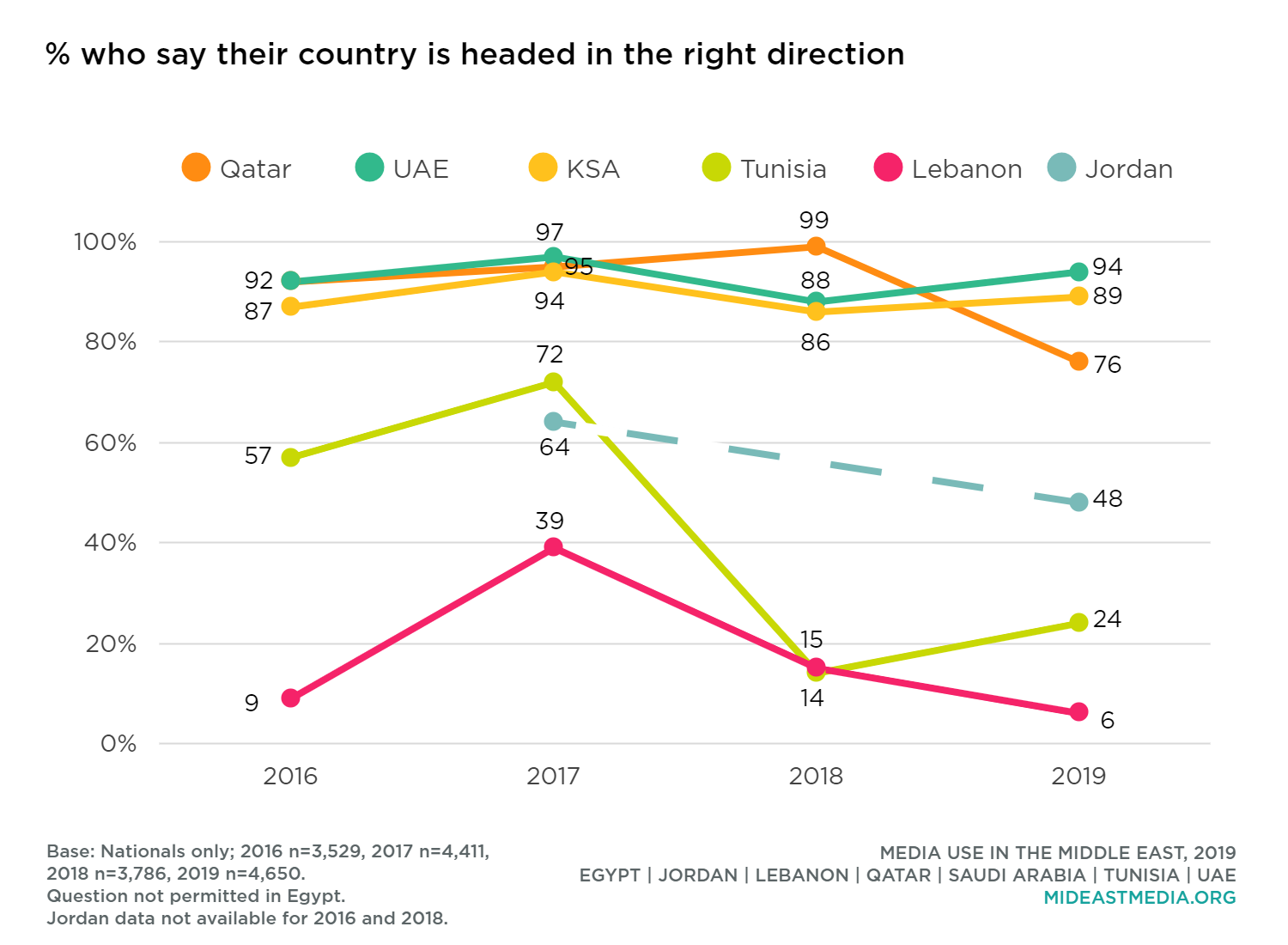

Arab nationals in some countries report less agreement on the trajectory of their countries. Significant majorities of Qataris, Emiratis, and Saudis say their country is headed in the right direction, though in Qatar the figure has fallen by 23 percentage points, to 76%, since 2018. Conversely, in Jordan, Tunisia, and Lebanon fewer than half of nationals say their country is moving in the right direction. Only 6% of Lebanese said their country is going in the right direction, and notably these 2019 data were collected in Lebanon before the sweeping demonstrations began in October.

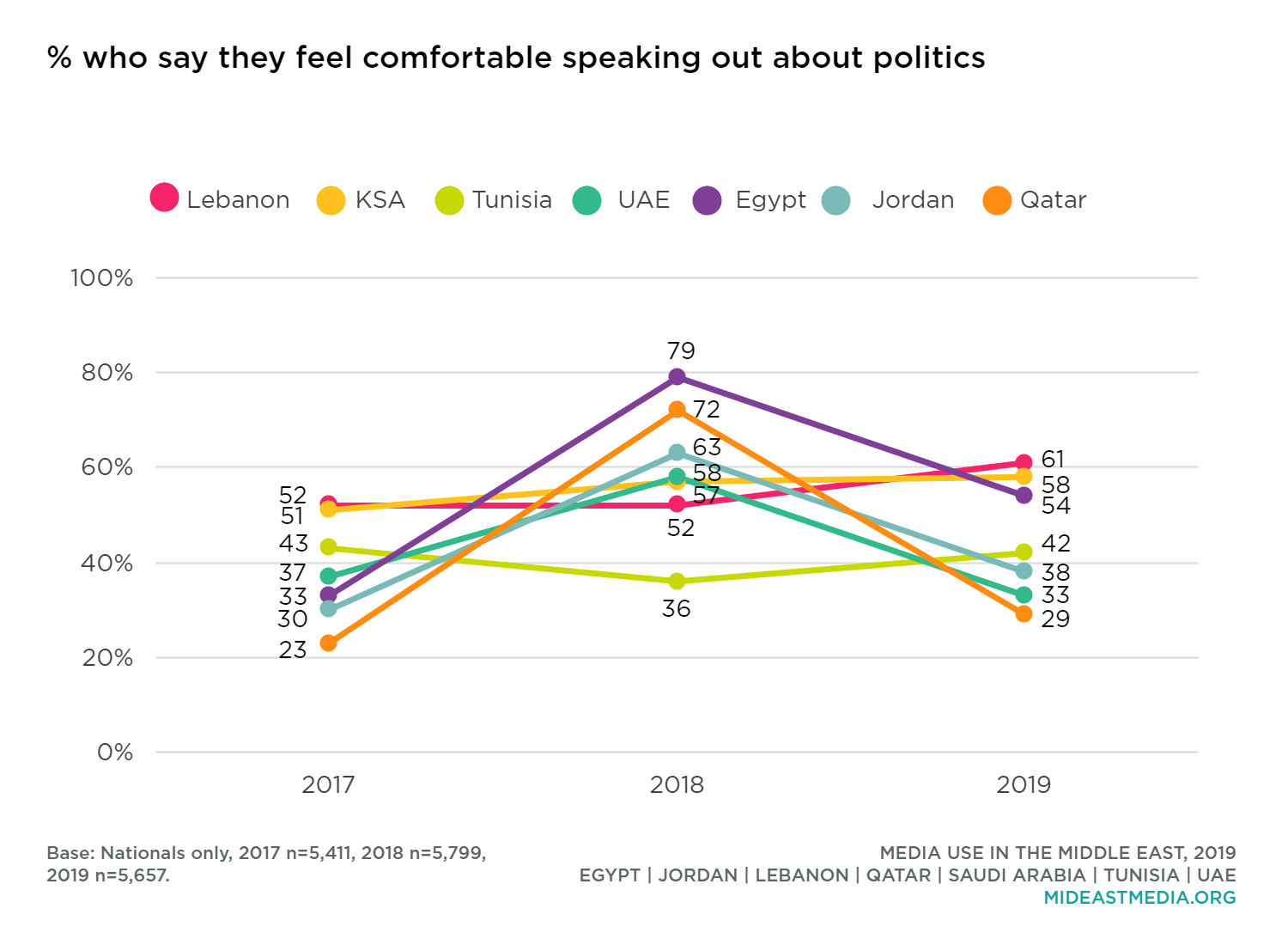

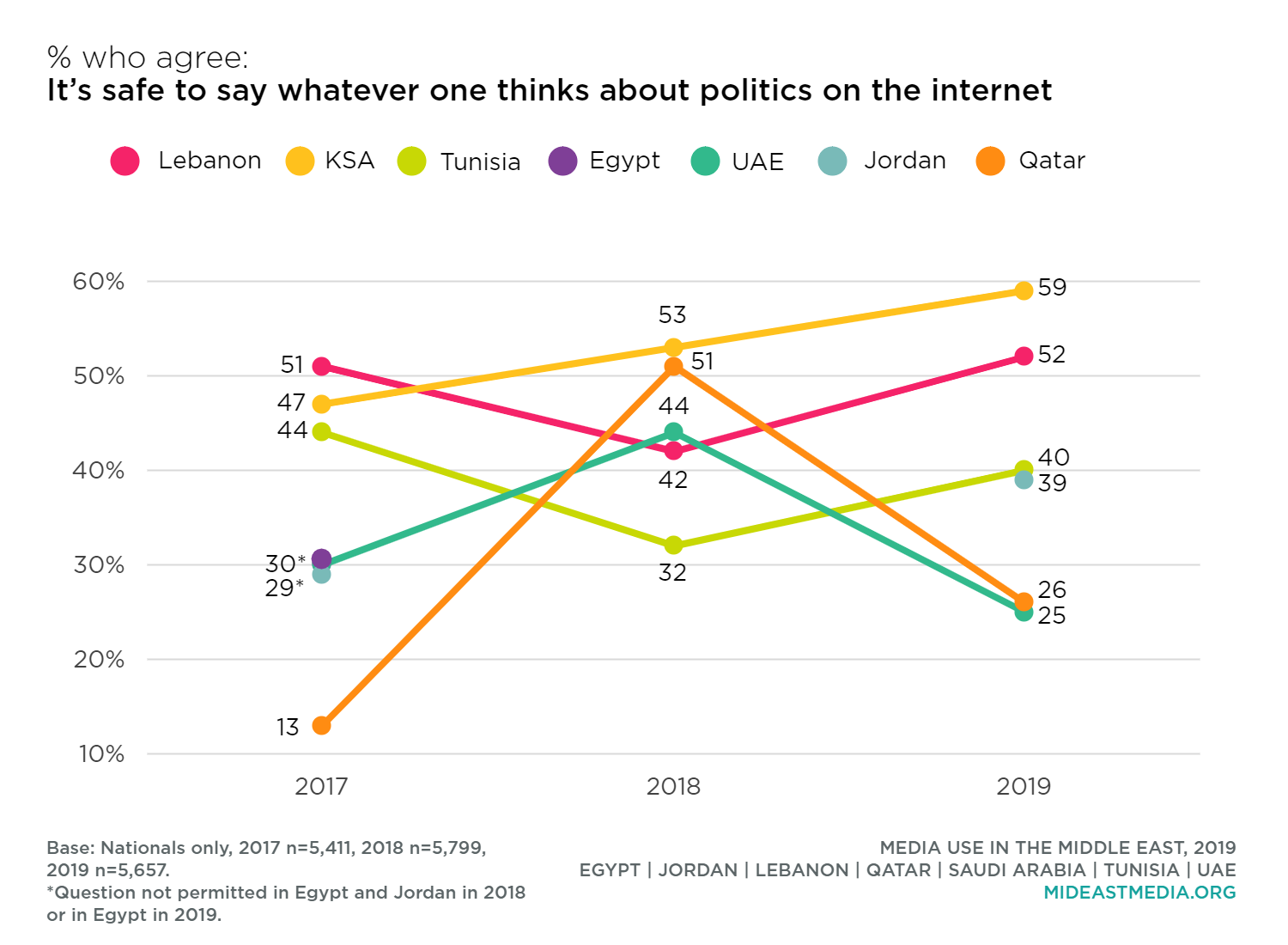

Between three and six in 10 nationals across countries feel comfortable speaking out about politics—Lebanese, Saudis, and Egyptians report much higher rates than Qataris, Emiratis, and Tunisians. Having peaked in 2018, confidence in speaking about politics has tempered across the region, declining since 2018 in every country except Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, and Tunisia, where there was a very modest rise.

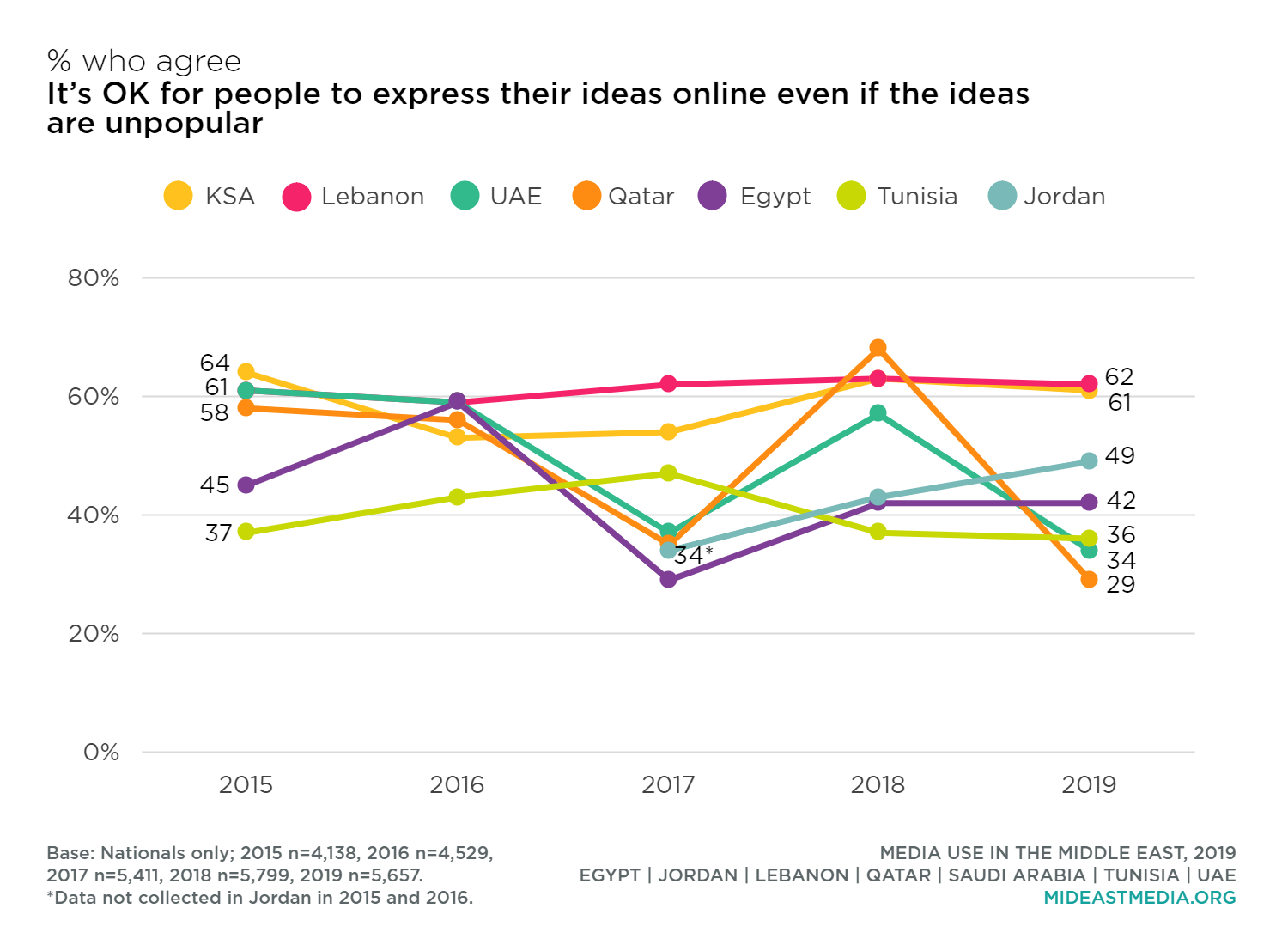

Between countries, nationals express marked differences in attitudes about protecting online speech. Most Lebanese and Saudis say people should be able to express ideas online even if the ideas are unpopular—changing little in the two countries over the past five years. Support for free speech online has been more variable in Qatar and the UAE, both recording a drop in agreement in 2017, a spike in 2018, and another drop in 2019.

Similar patterns hold for the measure “It is safe to say whatever one thinks about politics on the internet.” Saudis and Lebanese, again, are among the most likely to agree, by percentages up six and 10 points from 2018, respectively. Such agreement is far less likely among Qataris or Emiratis, however.

Majorities of nationals in all countries except the UAE and Qatar believe people should be able to criticize governments online; only one-quarter of Qataris and Emiratis agree. In Qatar, the figure fell from 48% in 2018.

Nationals in every country continue to increasingly reject government abridgment of speech, even potentially controversial speech. More likely are Lebanese and Tunisians than other nationals to say governments shouldn’t prevent criticism of governments. Emiratis and Qataris, however, are the most supportive of government regulating speech criticizing governmental policies as well as statements offensive to minorities or religions.

Majorities of nationals in most countries want the internet in their country to be more regulated: Lebanon (79%), Jordan (75%), KSA (68%), Egypt (60%), and Tunisia (52%). Qatar and the UAE, however, saw a sharp decline in support for greater internet regulation to only one in four (28% Qatar, 27% UAE).

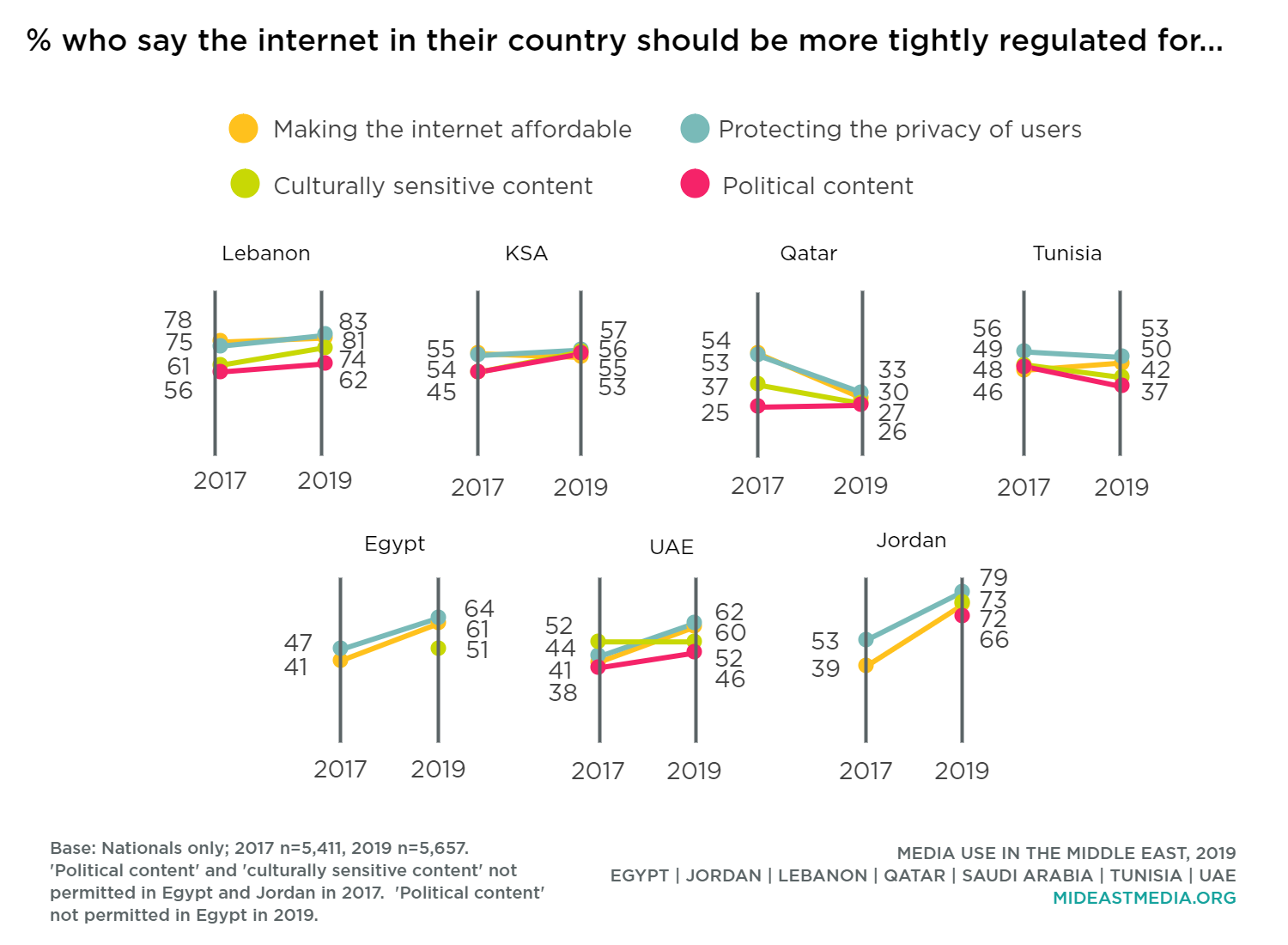

We learn more about what internet regulation means to many nationals in different countries by asking what specific regulations they want, such as making the internet more affordable, protecting user privacy, and monitoring political and culturally sensitive content. Qatar stands out on this measure, as less than a third of Qataris support any specific internet regulations, especially regulation of political and cultural content. Support for pro-social internet regulation—improving affordability and enhancing internet users’ privacy—has increased in in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and the UAE since 2017 and decreased in Qatar in the same time period.