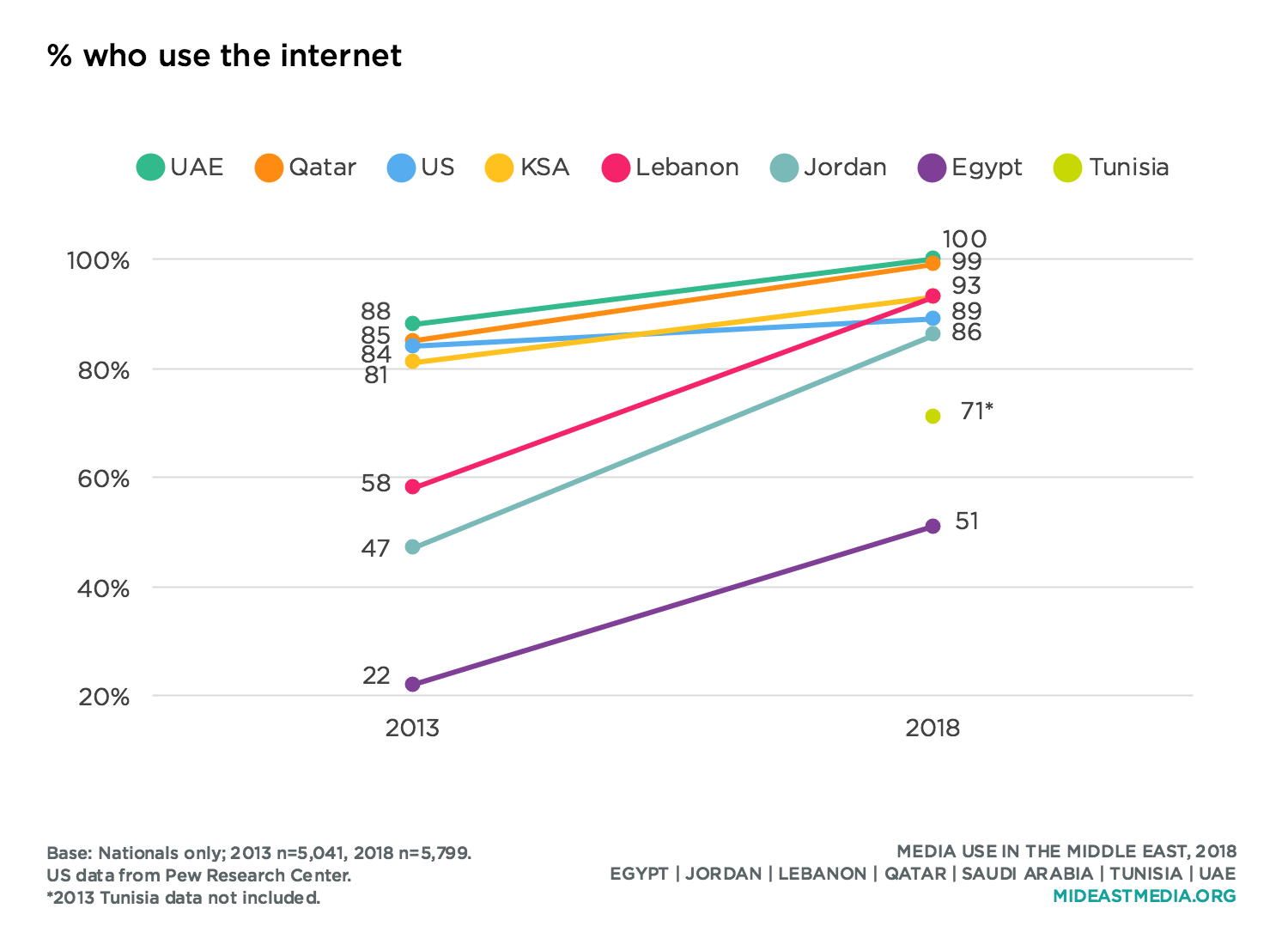

At least nine in 10 nationals use the internet in all surveyed countries except Egypt and Tunisia. Internet penetration in Egypt rose from two in 10 to half of Egyptians between 2013 and 2018, and penetration in Tunisia rose from about four in 10 to seven in 10 from 2014 to 2018. More nationals in Arab Gulf countries surveyed in 2018 use the internet than in the U.S., as 89% of Americans use the internet (Pew, 2018).

Most Arab nationals 18-24 years old were online in 2014, with a moderate increase since then (83% 2014 vs. 91% 2018). By comparison, internet use among those 45 and older more than doubled in the same time period, and now two-thirds of the oldest group are online (26% 2014 vs. 56% 2018).

There are significant differences in internet use across education levels. While there have been significant increases in internet penetration among the least educated Arab nationals since 2014, still fewer than one-third of those with a primary education or less are online (primary or less: 14% 2014 vs. 31% 2018; intermediary: 40% vs. 67%, secondary 71% vs. 86%, university or higher: 86% vs. 94%).

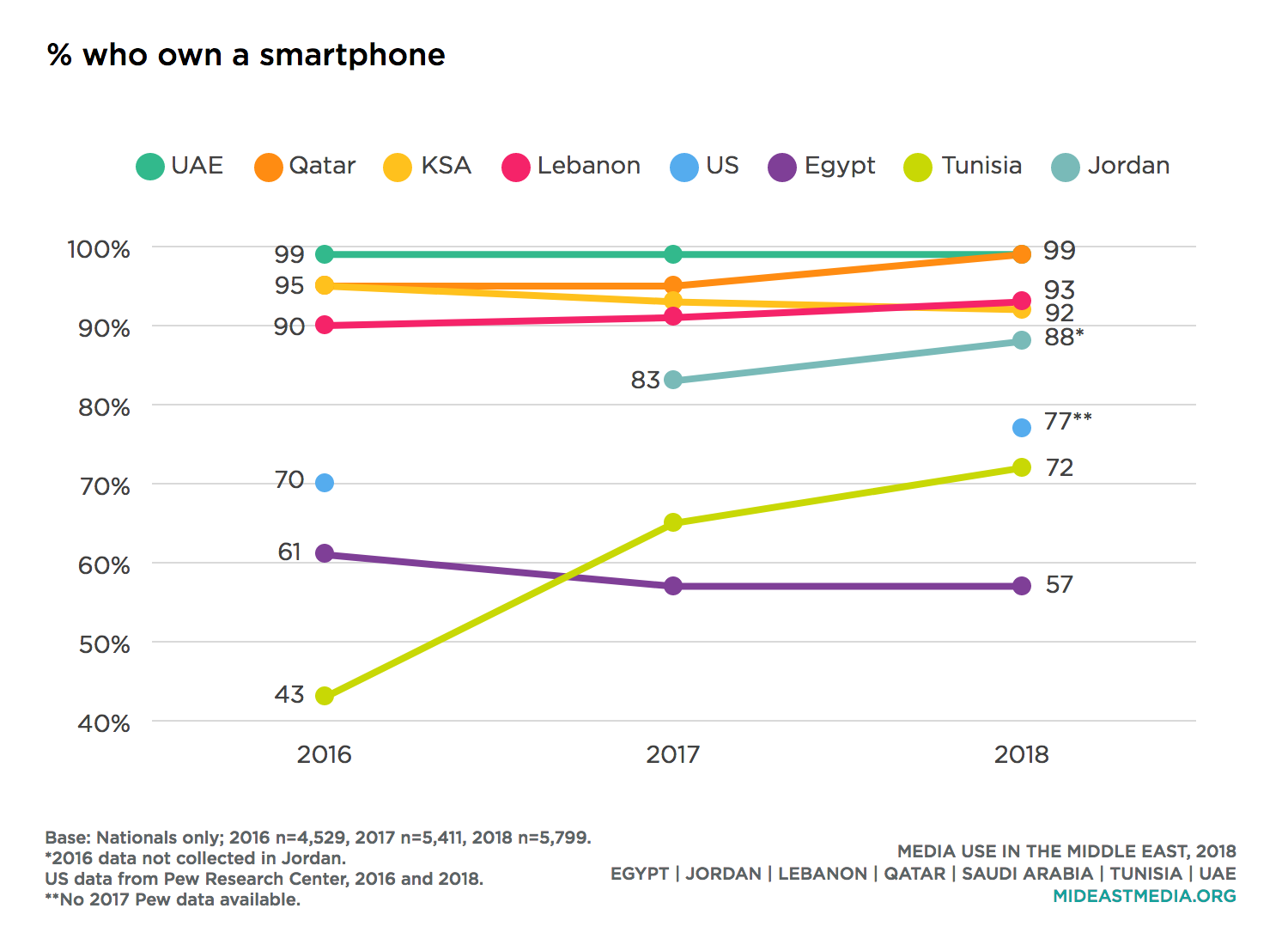

Nearly all Arab nationals own smartphones—at least nine in 10 across all countries surveyed except Egypt and Tunisia. Smartphone penetration in Tunisia increased by nearly 30 percentage points between 2016 and 2018, while remaining relatively unchanged in Egypt. Smartphone ownership in five of seven Arab countries studied here far exceeds the rate among U.S. residents (77% as of 2018, according to Pew).

The oldest (45+ year-olds) and least educated nationals (primary school or less) are less likely to own smartphones, but the gaps between respective cohorts are shrinking. Compared to 2016, smartphone ownership rose 10 percentage points among those 45 and older and nearly doubled among those with a primary education or less (age: 45+ year-olds: 49% 2016 vs. 59% 2018, 35-44 year-olds: 71% vs. 83%, 25-34 year-olds: 85% vs. 91%, 18-24 year-olds: 89% vs. 90%; education: primary or less: 19% 2016 vs. 36% 2018, intermediate: 65% vs. 72%, secondary: 79% vs. 87%, university or higher: 91% vs. 94%).

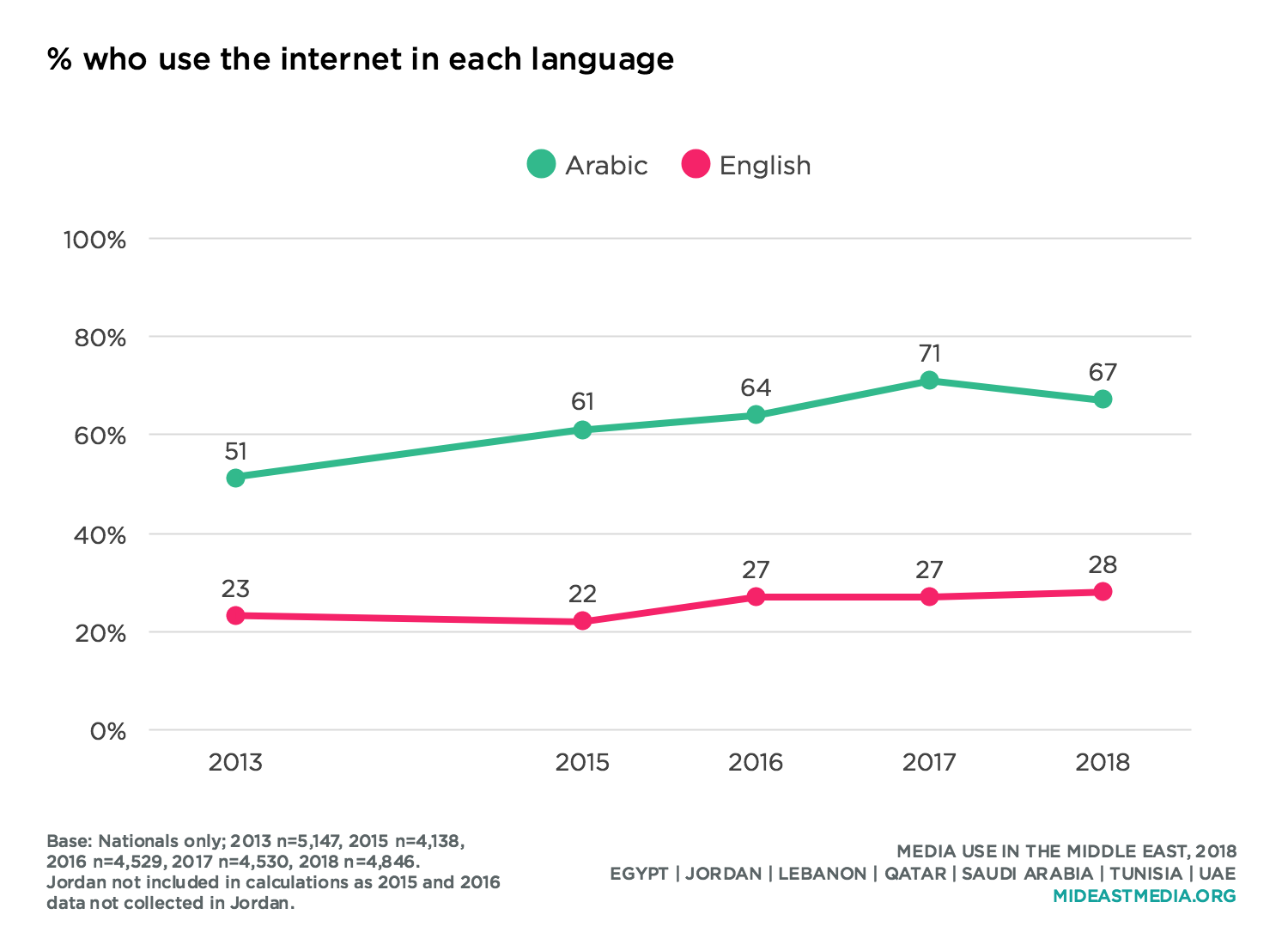

The languages in which Arab nationals use the internet have changed little since 2013 and reflect sustained predominance of Arabic. More than two-thirds of nationals utilize Arabic online, while just one-third of nationals use the internet in English. There are wide variations by country in using English online. Majorities of nationals in Lebanon use the internet in English, as do half in the UAE, but only about one in four or less in other countries access the internet in English (60% Lebanon, 49% UAE, 28% Qatar, 26% KSA, 22% Jordan, 15% Tunisia, 10% Egypt).

Additionally, while majorities of nationals in all age groups use the internet in Arabic, figures for English are lower among older respondents; four in 10 of the youngest, though only 13% of the oldest, nationals access the internet in English.

Not surprising, the percentage of nationals who access the internet in English rises sharply among more educated respondents (2% primary or less, 13% intermediate, 30% secondary, 43% university or higher).

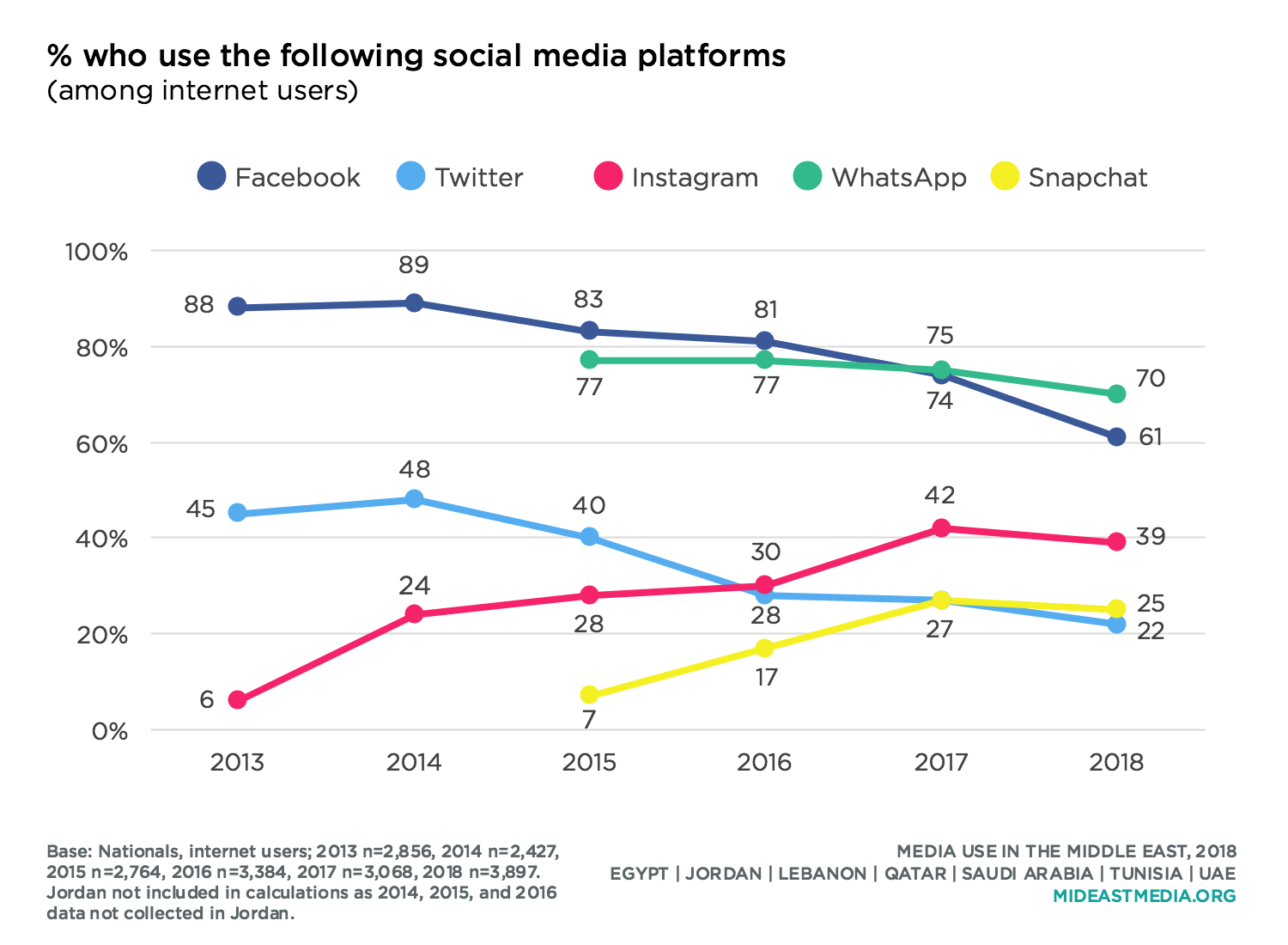

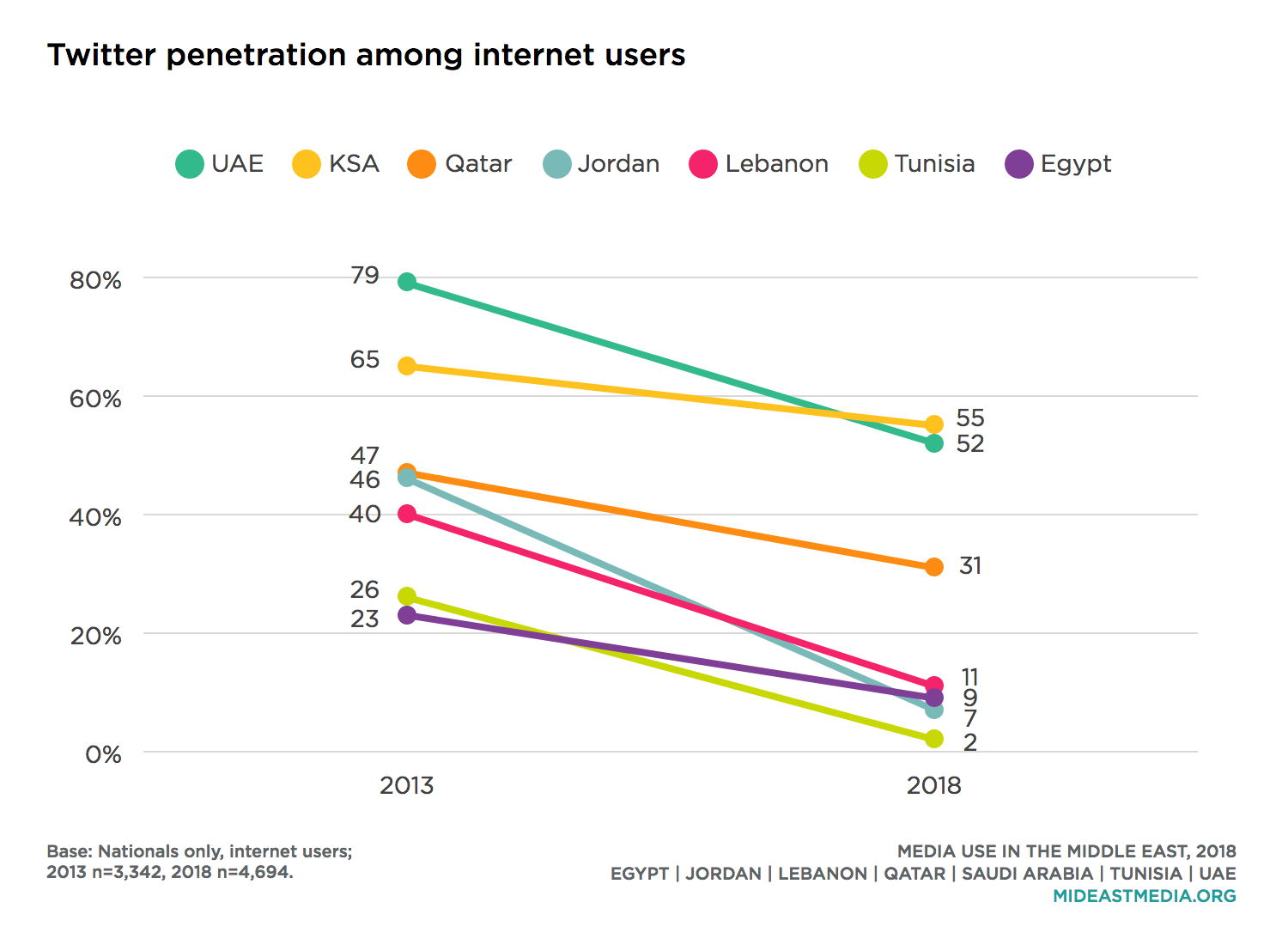

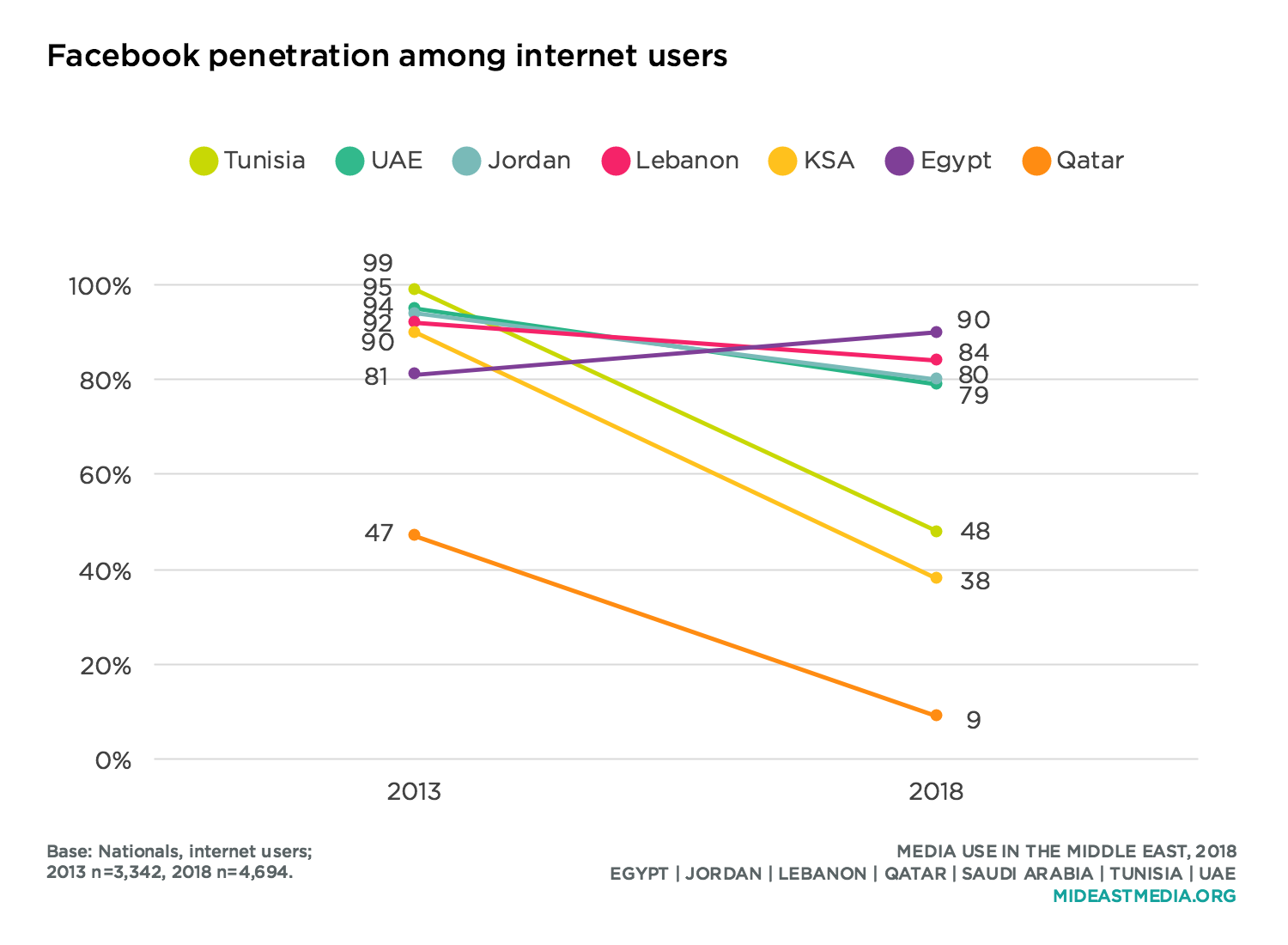

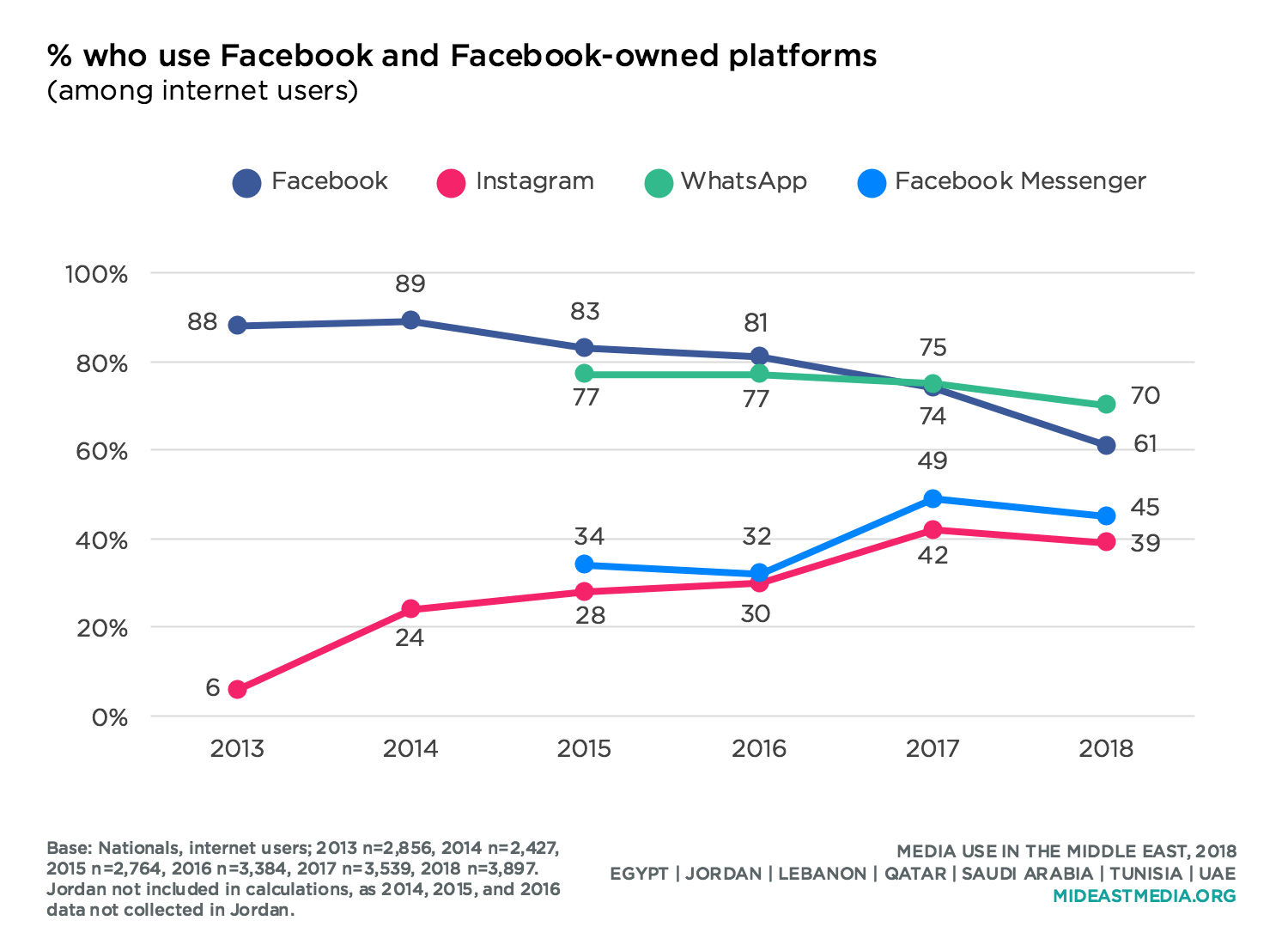

Since 2015 use rates of Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp have all fallen significantly among internet users. Facebook and Twitter, especially, have seen massive departures among Arab nationals. Both Snapchat and Instagram have risen in penetration since 2015, though both platforms have seemingly plateaued among Arab nationals who use the internet.

Qataris were always the least likely to use Facebook, but the share of Qataris who use the service nonetheless plummeted from about half in 2013 to 9% in 2018. The fall in Twitter penetration since 2013—use of the platform among internet users has fallen by half—reflects significant declines in every individual country surveyed.

Facebook owns several major social networking sites other than just Facebook proper, which employees at the company refer to as “the blue app.” Use rates for some other Facebook-owned platforms have fallen among internet users in Arab countries, too.

WhatsApp penetration among Arab nationals who use the internet dropped by 7 percentage points between 2015 and 2018. While Instagram and Facebook Messenger saw an approximate 10-point increase in the same period, use rates for both are either unchanged or fell between 2017 and 2018.

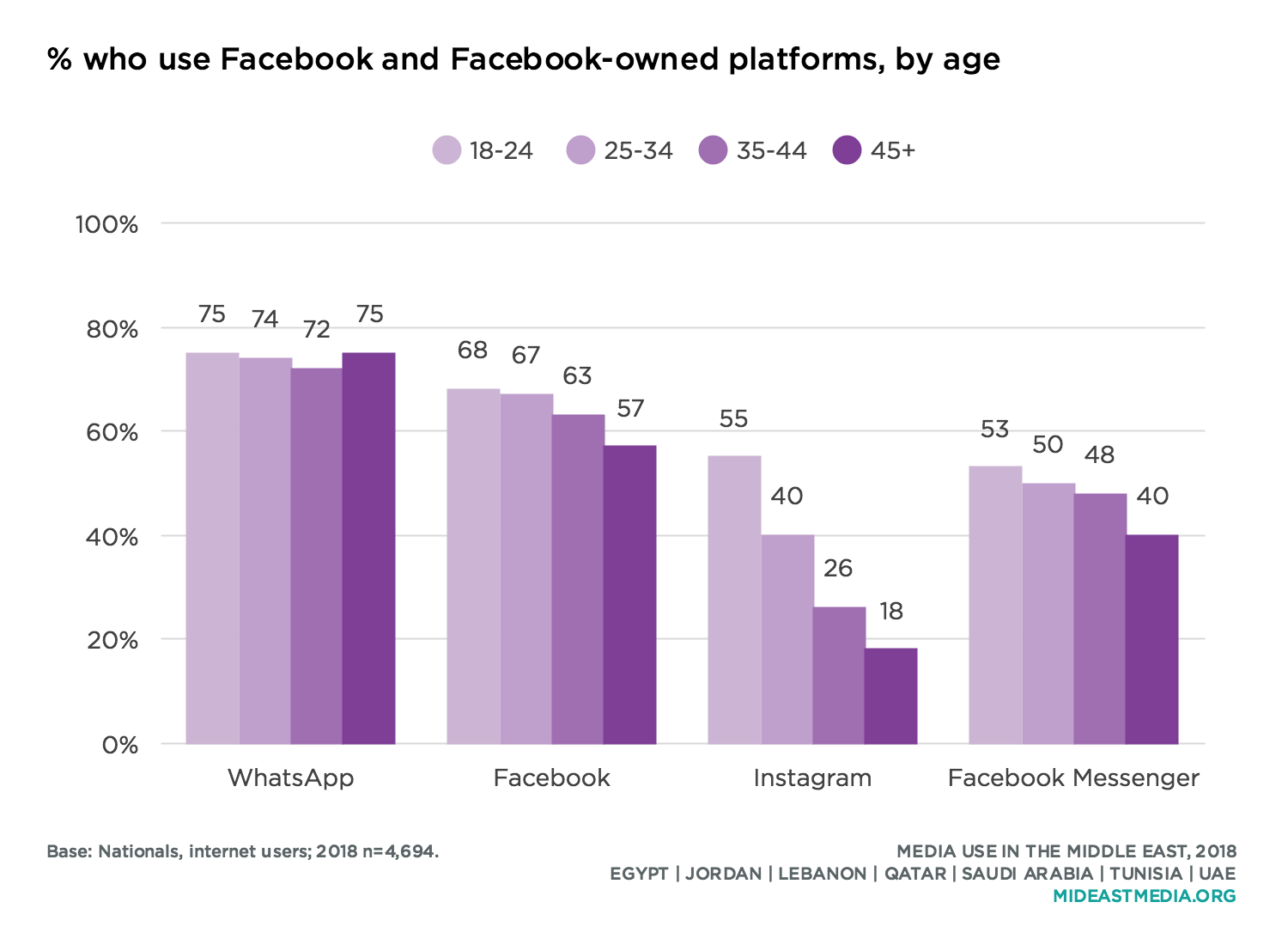

Older nationals who use the internet are no less likely than younger respondents to use WhatsApp, though Instagram and Snapchat are far more popular among the younger cohorts.

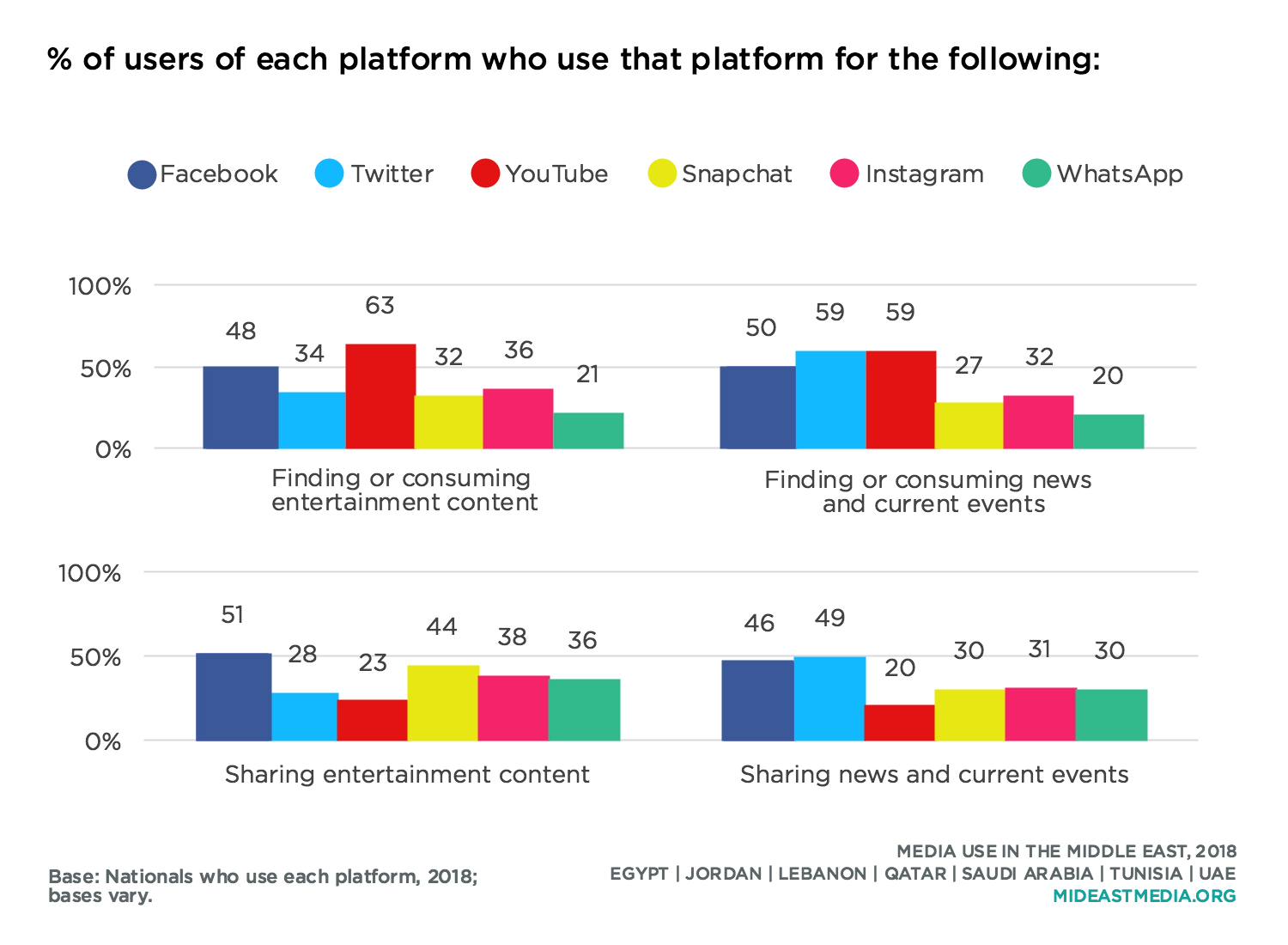

Among people who do use their platforms, Facebook and Instagram are utilized for a diverse set of reasons. Nearly half of Facebook users and 30 to 40% of Instagram users, for example, search for and share both entertainment and news/current events on the platform. Snapchat, not owned by Facebook, also serves multiple purposes among at least one-third of its users, but nearly half who use Snapchat share entertainment content on that platform, which is 14 percentage points higher than the proportion that shares news/current events on Snapchat. YouTube users, however, tend to use that platform for finding or consuming content (both news/current events and entertainment), rather than sharing content. Twice as many Twitter users get or share news on the platform as use it for entertainment ends.

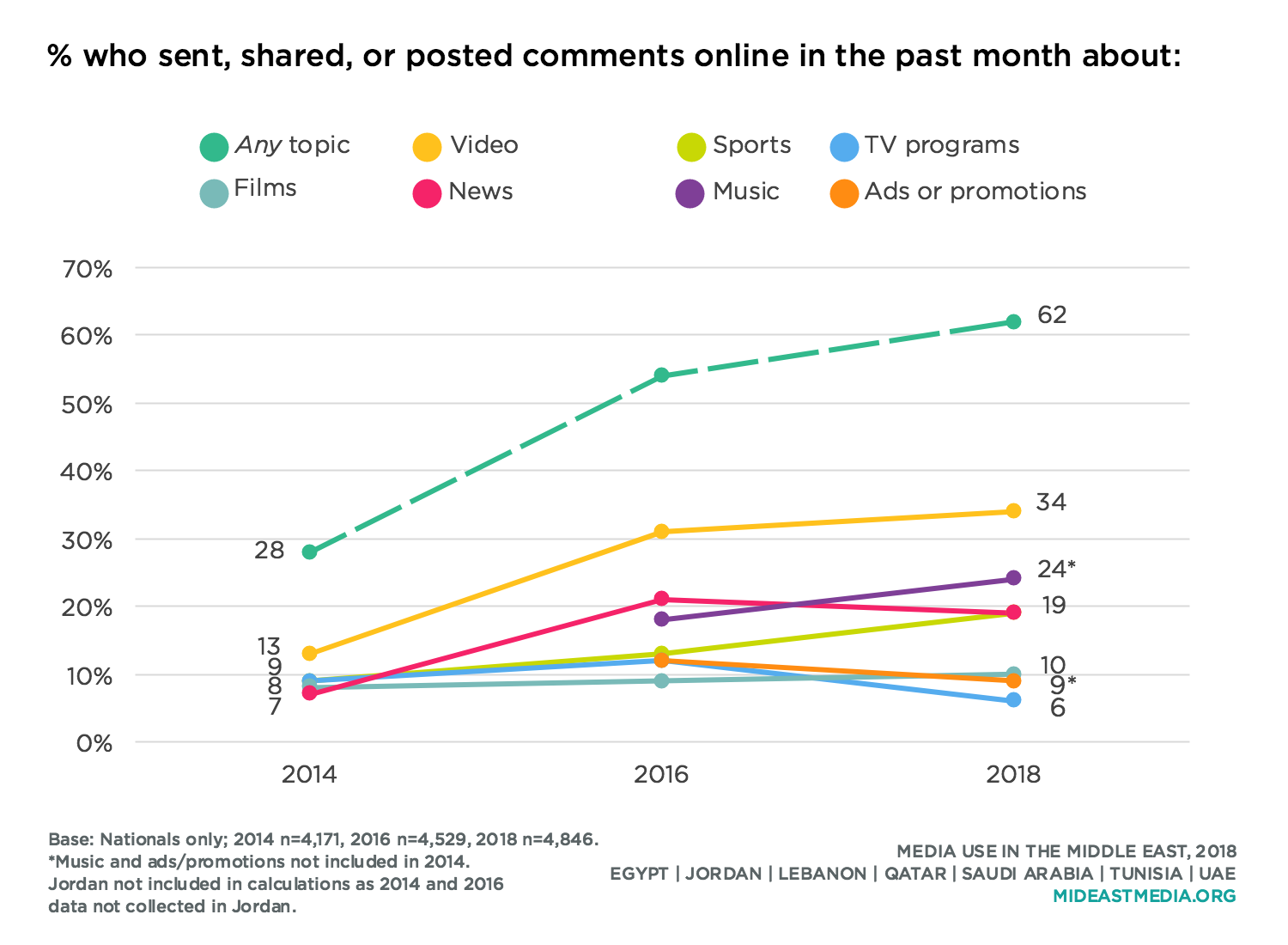

Between 2014 and 2018, the portion of Arab nationals who shared or commented on content online in the previous month more than doubled, to six in 10. Online video remains the most shared/discussed content—by one-third of nationals, up from 13% in 2014. More nationals in 2018 than 2016 also said they had shared about sports and music content in the prior month.

Majorities of men and women share content online, but men do so at a modestly higher rate than women (67% vs. 56% have shared/commented in the past month). Perhaps not surprisingly, younger and more educated nationals are more likely to share or comment online, but, notably, even four in 10 of those 45 and older and a quarter with a primary education have shared in the past month (age: 73% 18-24 year-olds, 71% 25-34 year-olds, 60% 35-44 year-olds, 39% 45+ year-olds; education: 77% university or higher, 65% secondary, 51% intermediate, 23% primary or less).

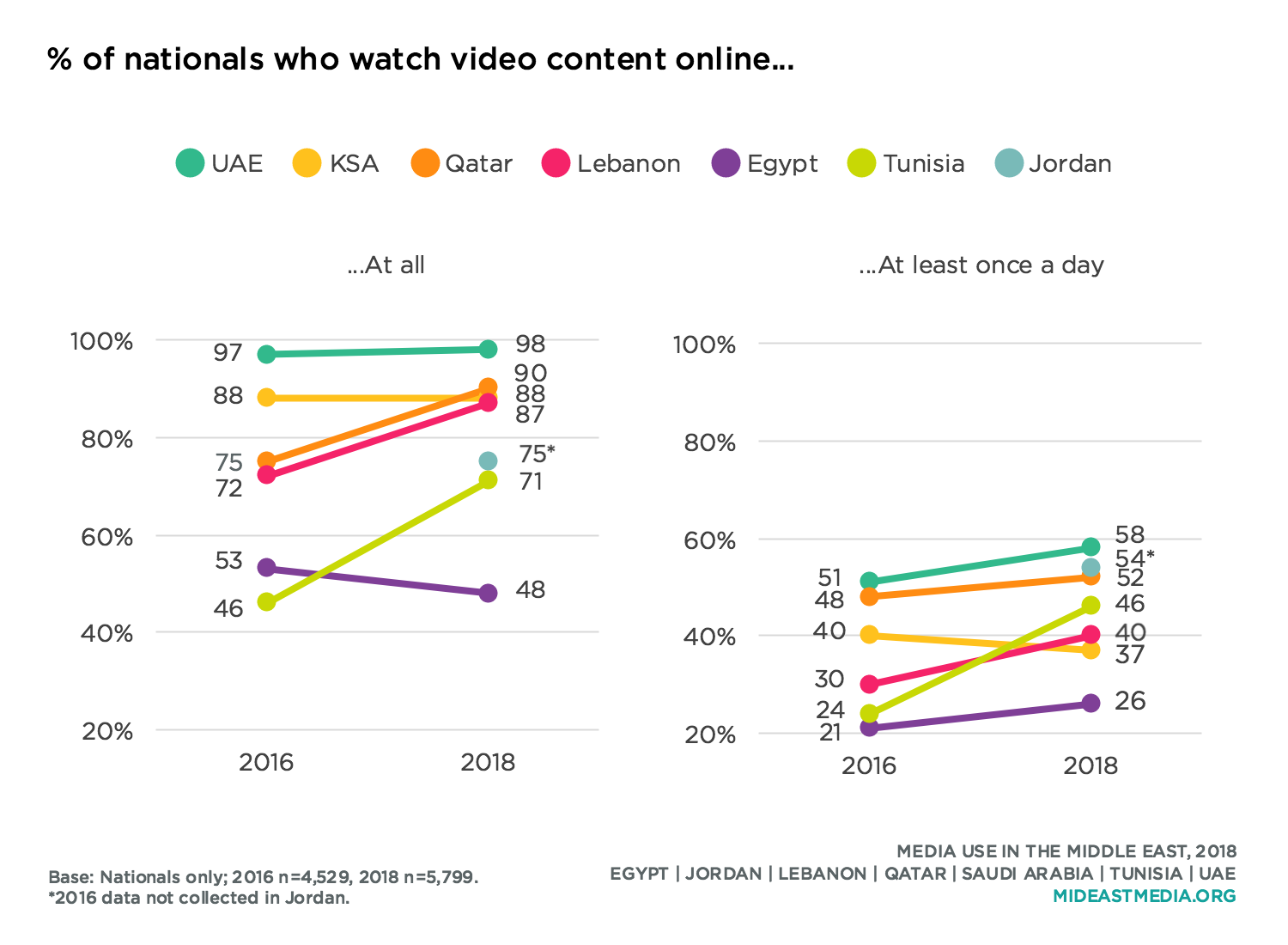

Large majorities of nationals watch online video content, and many do so every day. While almost all Emiratis and Saudis watch online video, which has been the case since 2016, the shares of nationals in Qatar, Lebanon, and Tunisia who do same have increased. About half or more of Emiratis, Jordanians, Qataris, and Tunisians watch online video content every day.

Nearly all 18-24 year-olds watch some online video, and more than half do so at least once a day (watch at all: 89% 18-24 year-olds, 85% 25-34 year-olds, 75% 35-44 year-olds vs. 49% 45+ year-olds; watch at least once a day: 55% 18-24 year-olds, 48% 25-34 year-olds, 41% 35-44 year-olds vs. 23% 45+ year-olds).

About half of nationals have watched music video online in the past six months, nearly 40 percent watched films online and one-quarter watched TV content online in the same time period, representing an increase since 2016 for music and TV content (music: 41% 2016 vs. 48% 18%, TV shows: 21% vs. 29%).

Nationals of all age groups are most likely to access music online, followed by films and then TV content. Use rates for all three—music, films, and TV programs—vary by age, and are higher for younger age groups (music: 62% 18-24 year-olds, 55% 25-34 year-olds, 43% 35-44 year-olds, 22% 45+ year-olds; films: 52%, 44%, 31%. 16%; TV programs: 33%, 32%, 23%, 11%). Of note: older nationals are more likely to access news online than entertainment content, though more than half of nationals in younger cohorts also access news online (news: 52% 18-24 year-olds, 53% 25-34 year-olds, 47% 35-44 year-olds, 29% 45+ year-olds).

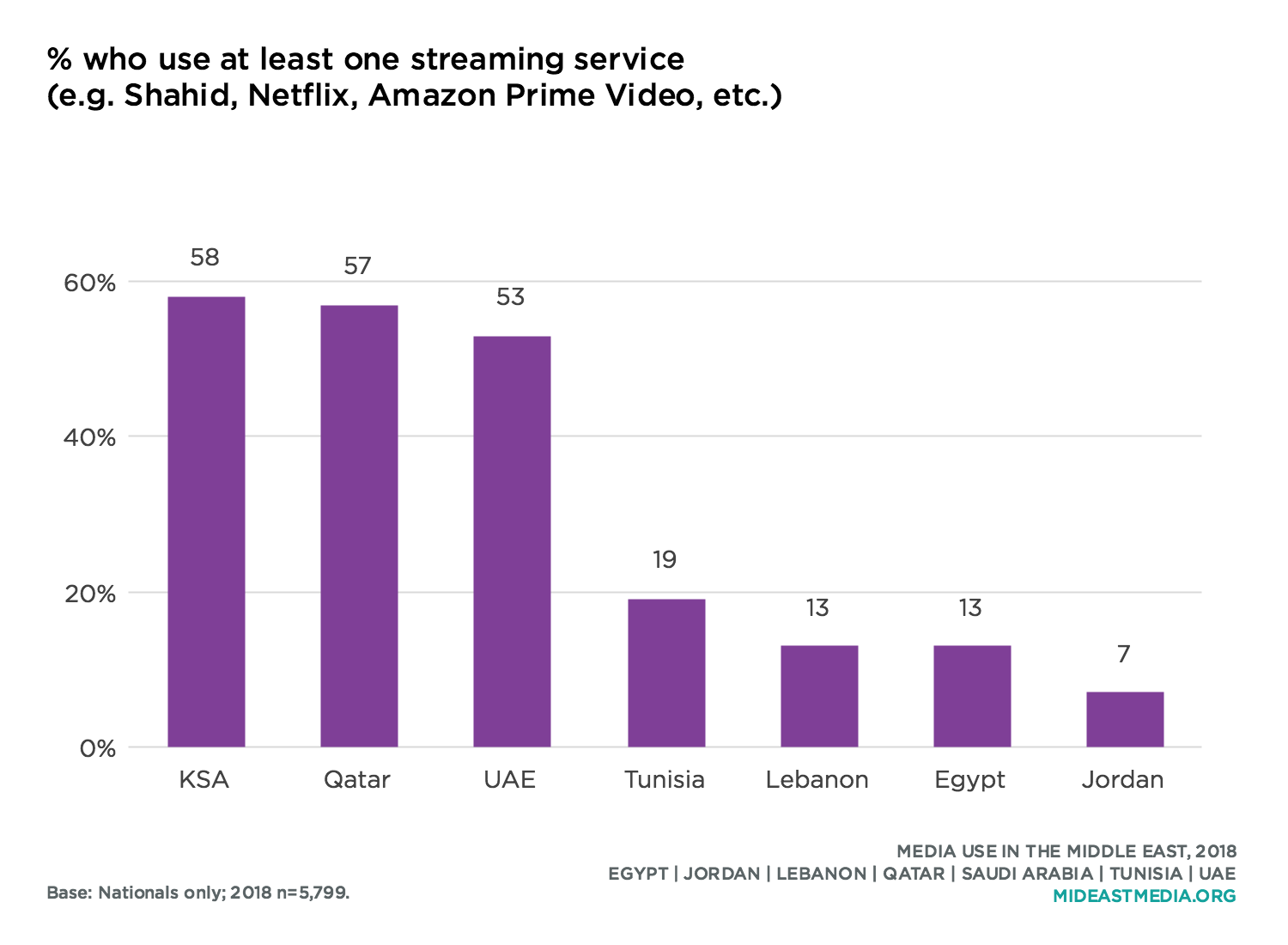

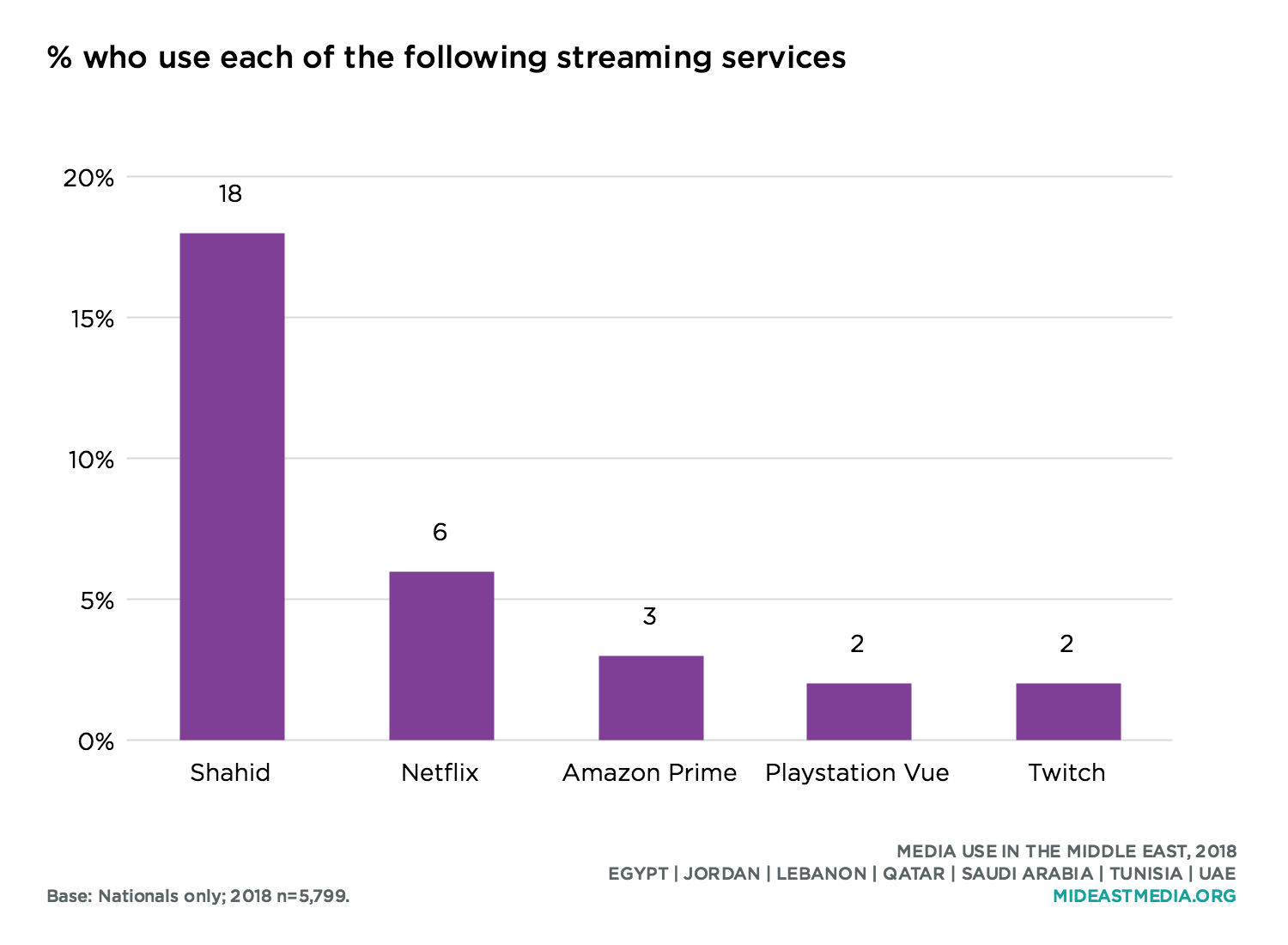

Use of online streaming services varies across the region, though Shahid has the greatest market share in all countries. Netflix is currently runner-up, and is used by a larger share of Qataris than other nationals.

Nationals from Gulf countries are far more likely than other than other nationals to use any streaming service. It is worth mentioning that some streaming services are not available in Arab countries without a VPN, while others have been made available only in recent years. Amazon Prime Video requires a VPN, while Netflix only became available in some Arab countries in 2016. Amazon Prime Video content is also inaccessible to some non-holders of U.S. or U.K. credit cards.

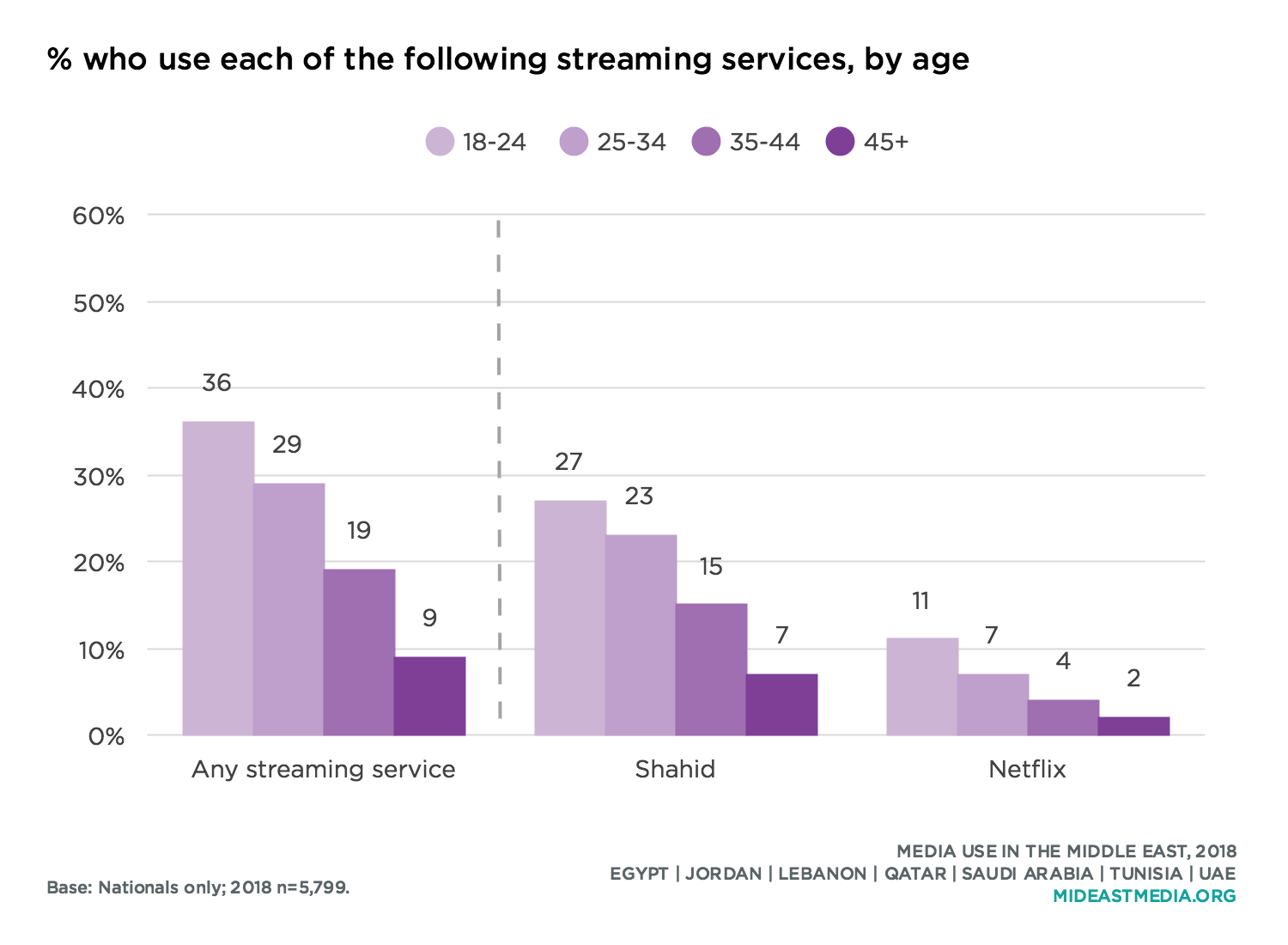

Streaming services are used most widely among younger nationals. Those under 25 years old use streaming services at about four times the rate of those 45 years and older.

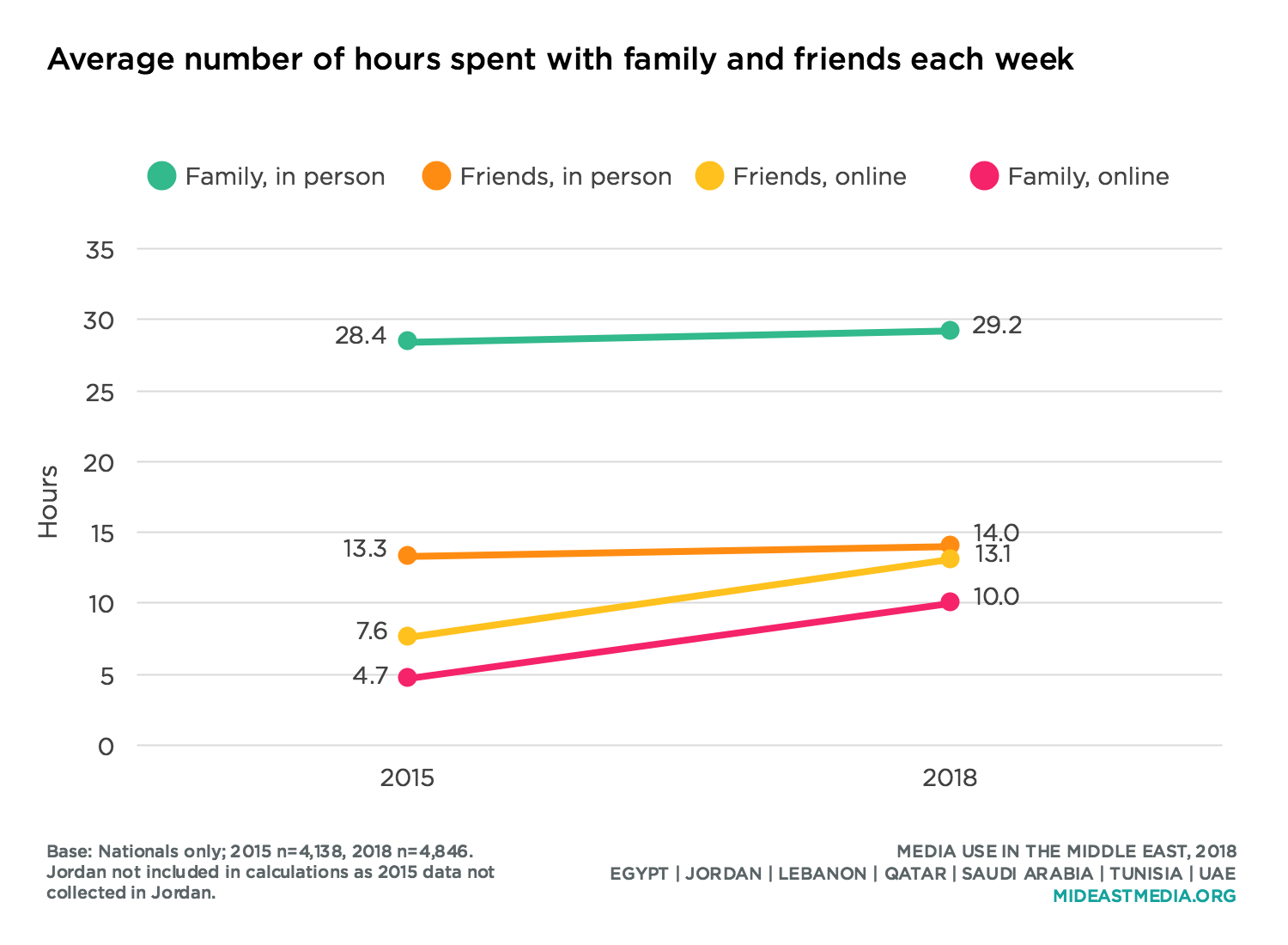

In-person time with family has not diminished in Arab countries the last several years, despite increasing digital connectivity. Nationals consistently report spending double or more the amount of time each week with family than with friends in person, with friends online, or with family online. Time spent online with friends and family did, however, rise by a few hours on average since 2016.

In-person time with family among Arab nationals was unchanged from 2015 to 2018 (28 hours each week in 2015 vs. 29 hours in 2018). In-person time with friends also remained unchanged (13 hours per week in 2015 vs. 14 a week in 2018). In-person time with family varies considerably by country, however; Emiratis spend nearly twice as much time with family each week as Egyptians and Tunisians do (47 hours UAE, 40 Jordan, 35 Lebanon, 29 Qatar, 27 KSA, 25 Egypt, 24 Tunisia). Tunisians, on the other hand, spend the most time each week with friends (19 Tunisia, 15 KSA, 15 Qatar, 15 UAE, 14 Lebanon, 12 Jordan, 11 Egypt).

Online interactions with family and friends have both increased by five hours per week from 2015 to 2018, and Arab nationals now spend almost as much time each week socializing online with friends as socializing in-person with friends (online with friends: 8 hours each week in 2015 vs 13 hours in 2018; online with family: 5 hours in 2015 vs. 10 hours in 2018). Qataris spend the most time each week socializing online with others, both family and friends (online with friends: 22 Qatar, 19 Tunisia, 14 UAE, 12 KSA, 12 Lebanon, 9 Egypt, 8 Jordan; online with family: 15 Qatar, 13 Tunisia, 13 UAE, 13 KSA, 8 Lebanon, 7 Jordan, 4 Egypt), which may be due to the fact that Qataris spend more time using the internet for any purposes than nationals in all other countries surveyed.

Men and women spend similar numbers of hours each week online with friends and with family. On average, however, women spend seven additional hours each week with family in-person than men do, and five fewer hours face-to-face with friends than men.

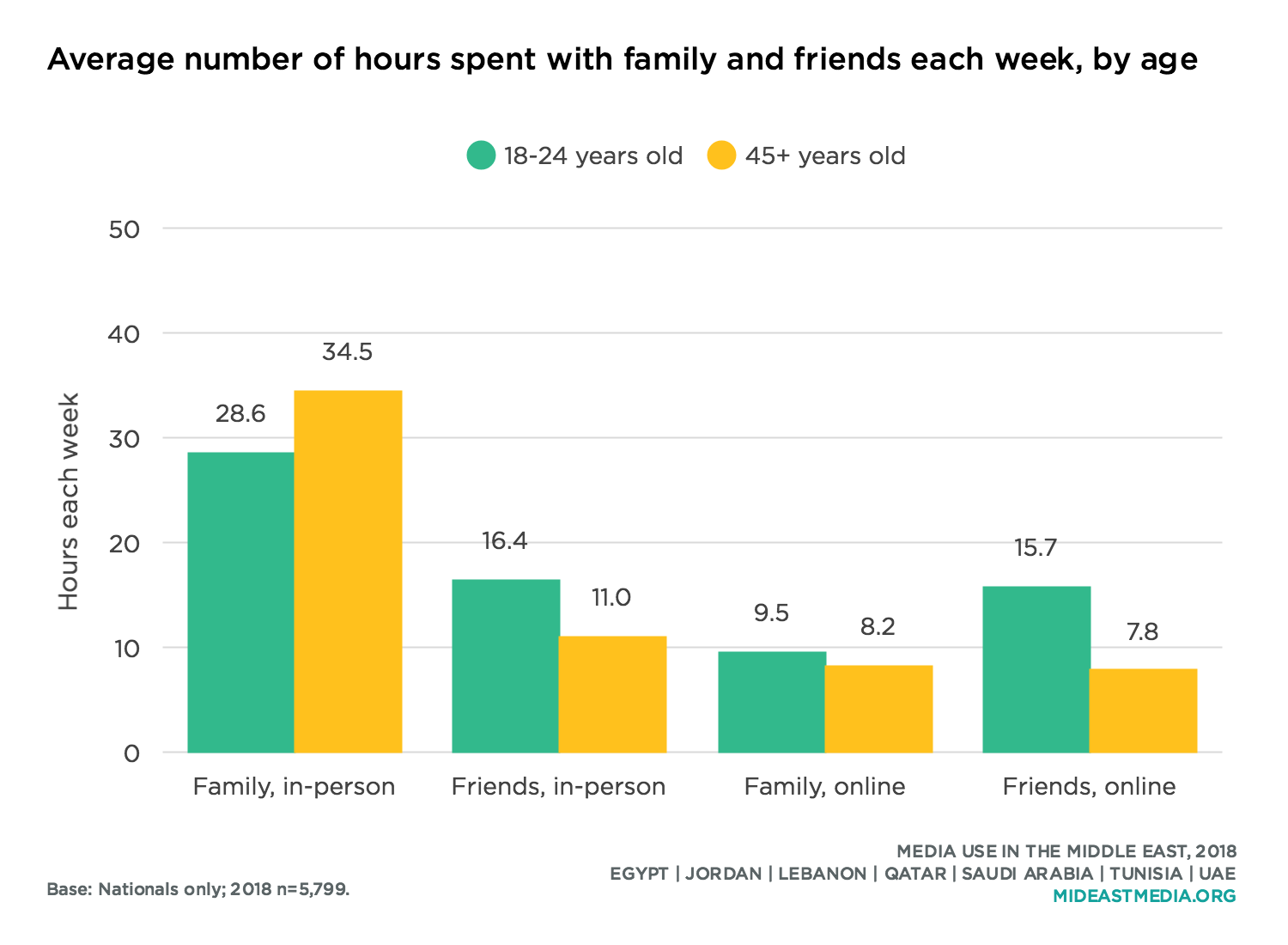

While all age groups spend majorities of their in-person time with family, younger nationals spend more overall time with friends both in-person and online than do older nationals. In contrast, nationals 45 years and older spend six more hours per week in-person with family than do those under 25 years-old, on average.

Social Media Use in a Post-Blockade Middle East

Leah Harding, Al Jazeera English

Arabs are some of the most social people on the planet. Weddings and funerals last for days and social gatherings are the lifeblood in keeping culture alive. Family is first and decisions are made as if in a tribe: you consult one another and accept the majority rule. The same is especially true in the Gulf States, with tribalism only decades removed from modern society. Family is still king and the importance of each individual and how they interact has not changed. However, what has morphed over the years is the means with which these members communicate. Enter: social media.

In June 2017, Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates led a blockade against Qatar. As a result, families were split, students were forced to withdraw from school, and travel times between the countries increased as airfare prices skyrocketed. With this divide, the need to communicate online increased. It is not surprising then to see an increase (even slightly) in social media use in Qatar and the UAE, perhaps as family members from both countries try to stay in touch despite their governments’ disagreements.

At the beginning of the blockade, I was tasked with interviewing dozens of Qataris to ask them how life would change if the blockade continued. I used Instagram and Twitter to find individuals to speak to, though most of them felt most comfortable texting directly via WhatsApp. I did not use Facebook to reach interview subjects, as the platform’s popularity in Qatar is rather low, but instead, Snapchat and Instagram are my go-to apps.

And across the region, women are more likely to decline interviews via social media, which is understandable as they are not as active on social media as their male counterparts. When women are active on social media, they gravitate toward apps like Snapchat and Instagram (specifically the Story feature) because of the time limits to posts, and the increased privacy features that allow them to maintain a level of secrecy in their online accounts. Snapchat specifically appeals to women who do not want to show their faces, because of the filters they can choose to cover their faces or otherwise enhance different features on their face to hide their actual appearance.

WhatsApp is the most popular social media app among the countries surveyed. For one, it’s encrypted, ensuring your government is not listening in on your conversation. Even after encrypted calls were blocked in Qatar after the blockade, the usage of these tools still went up, as did the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). Interestingly, Qatar and the UAE both saw an increase in WhatsApp use, likely because of the platform speed, increased privacy options, and not needing to update a profile.

When it comes to sports, the blockade and 2018 FIFA World Cup seemed to play a role in media consumption in Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Qatar-based beIN Sports channel was the sole rightsholder for the FIFA World Cup in the region (including Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia, and the UAE) but in 2017, Saudi Arabia blocked access to it from within the Kingdom. Following this move, a spin-off network called ‘beoutQ’ started airing matches within Saudi Arabia. beIN called on Saudi Arabia to stop airing the pirate network, but Saudi Arabia maintains its innocence. Regardless, the demand for football clearly superseded politics and piracy in 2018, illustrated by the growing demand for paid sport subscriptions.

Economically it makes sense that Egypt and Saudi Arabia are the only two countries in this study that show a decline in internet and smartphone usage. Both countries have struggling economies and are experiencing tightening freedom of expression. According to the Freedom of Thought and Expression Law Firm, at least 496 websites were blocked between May 2017 and February 2018 in Egypt. Yehia Ghanem, an exiled Egyptian journalist, told Al Jazeera that Egypt’s government now owns 95 percent of its TV channels.

The language Arabs choose to use online is also fascinating. The rise in Arabic and the decline in English is perhaps the opposite of what these countries want to see, especially for Qatar who invest an incredible amount into Western world-class education for their citizens. The UAE’s rise in English on the internet perhaps makes it more marketable on a global stage. That being said, there is also a growing amount of Arabic content online that wasn’t there before, as the Arabic language saturates more of the internet.

A sad growing statistic is the amount of time Qataris, Saudis, and Tunisians are spending online instead of with their families. It is common across the Middle East to have group gatherings in parking lots, front porches, and at the majlis, and such daily social events are really the core of Arab culture in many ways. This is the time when families and friends bond and the ties between the units are strengthened. Arabs (as a whole) tend to wake up late and stay up late with many friends and family around. What has become more common, however, is to see groups together, but on their phones. I will often drive by Land Cruisers with Qataris inside while everyone (including the driver) is on their electronic device.

Social media has clearly shaped one of the most ancient civilizations on the planet, but will technology ever be able to replace social interactions for a culture that thrives on community living?