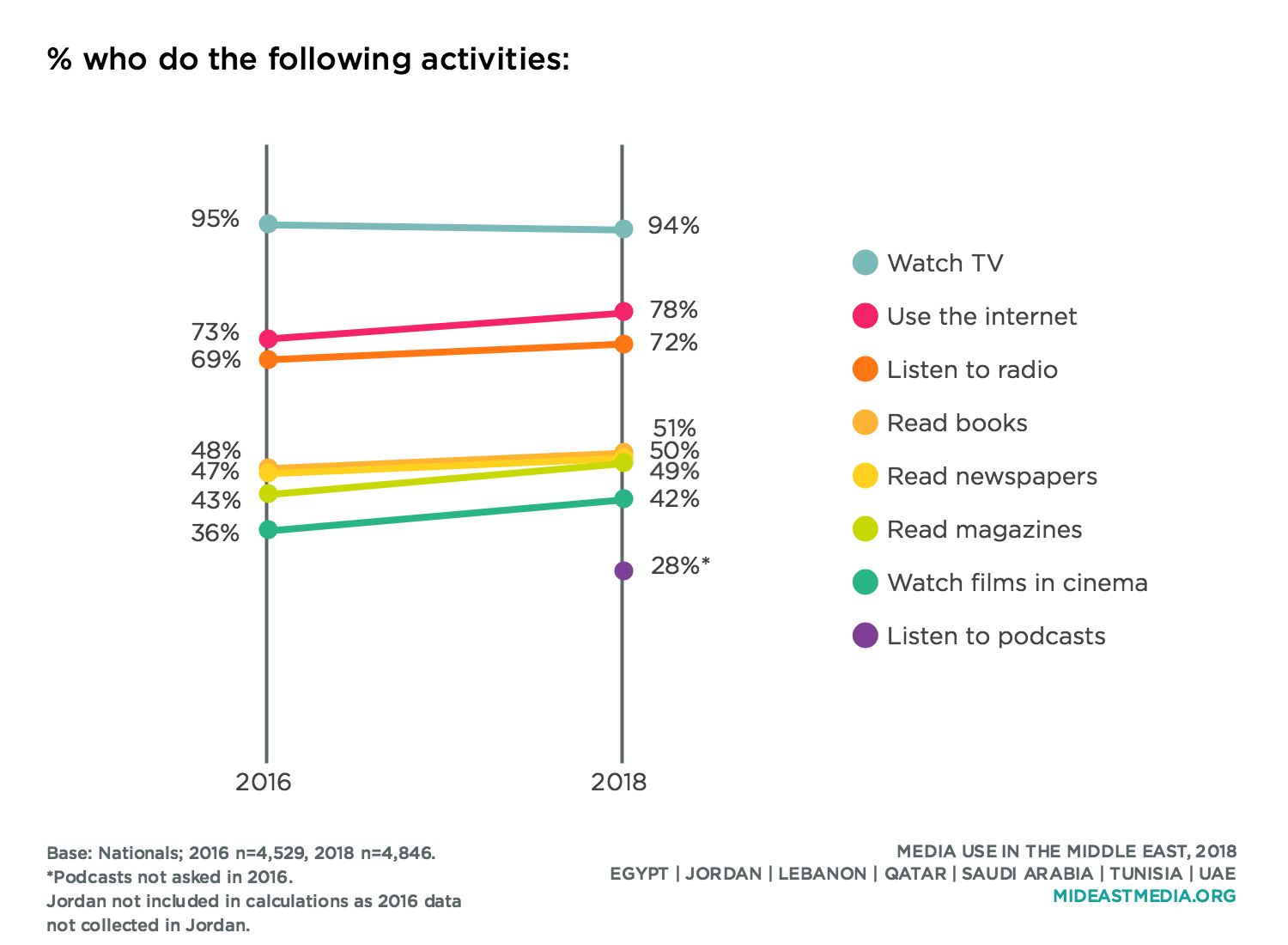

The proportions of Arab nationals who regularly access entertainment on a range of digital and non-digital platforms are increasing, but not for TV. While the share of nationals who watch TV is greater than that for any other medium, and is close to saturation in most countries, daily use of TV fell significantly since 2016 (64% of nationals surveyed in 2016 vs. 54% in 2018), while daily use of certain other platforms rose in the same time period (watch any online video content: 30% in 2016 vs. 40% in 2018; listen to music online: 22% vs. 28%; watch films online: 9% vs. 15%).

Moreover, the percent of nationals who watch specific types of TV—series, films, news, and music on a TV set—dropped by about 10 percentage points each since 2016. At the same time, the percentages of nationals who access these same media genres online, and also on a phone specifically, grew by about five to 10 percentage points.

.png)

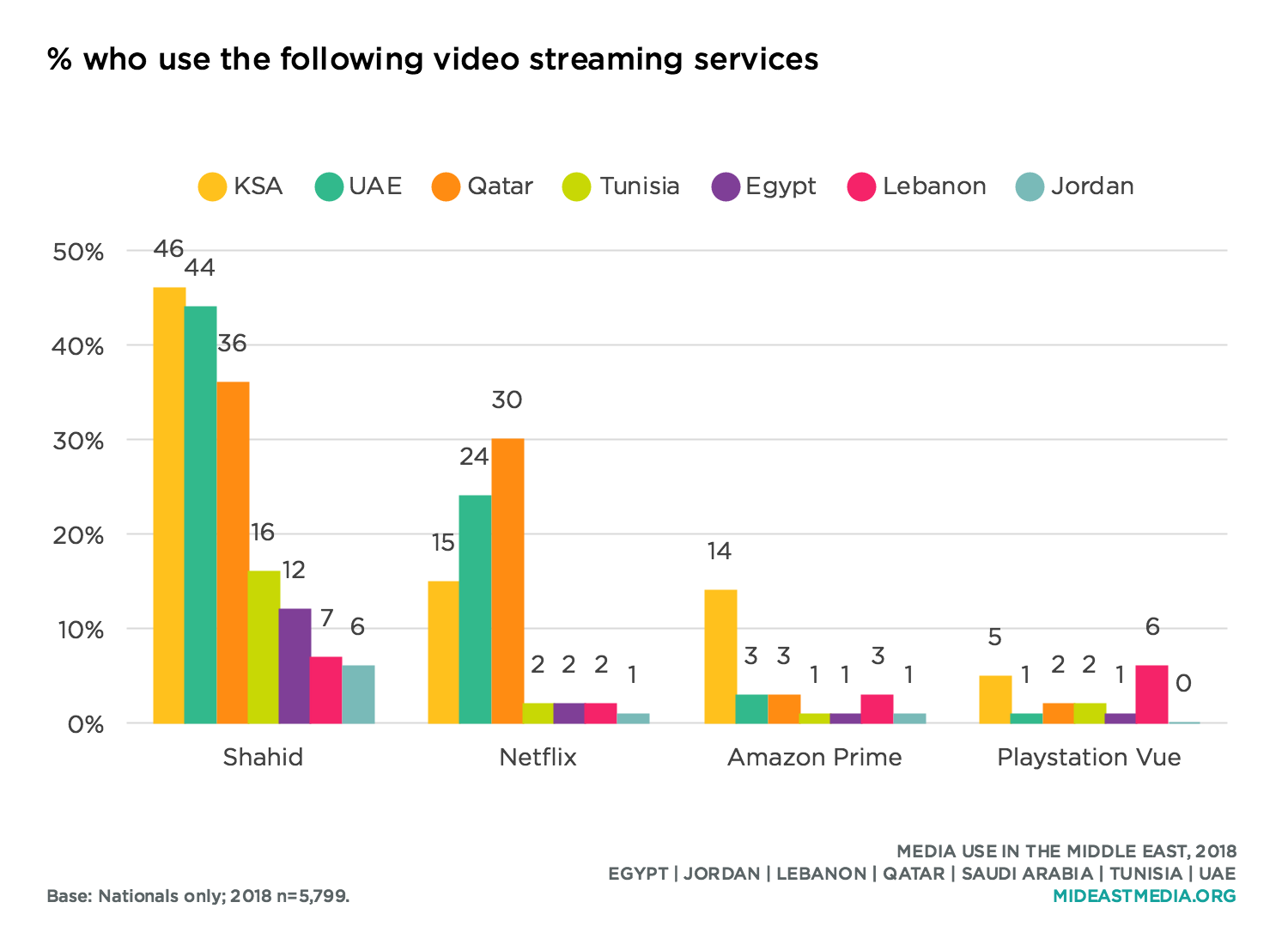

Nationals in Arab Gulf countries are much more likely to use streaming services than nationals in middle-income countries in the survey. More nationals use Shahid than any other service, while Netflix is a distant second—except in Qatar, where both are used by about one-third of

nationals.

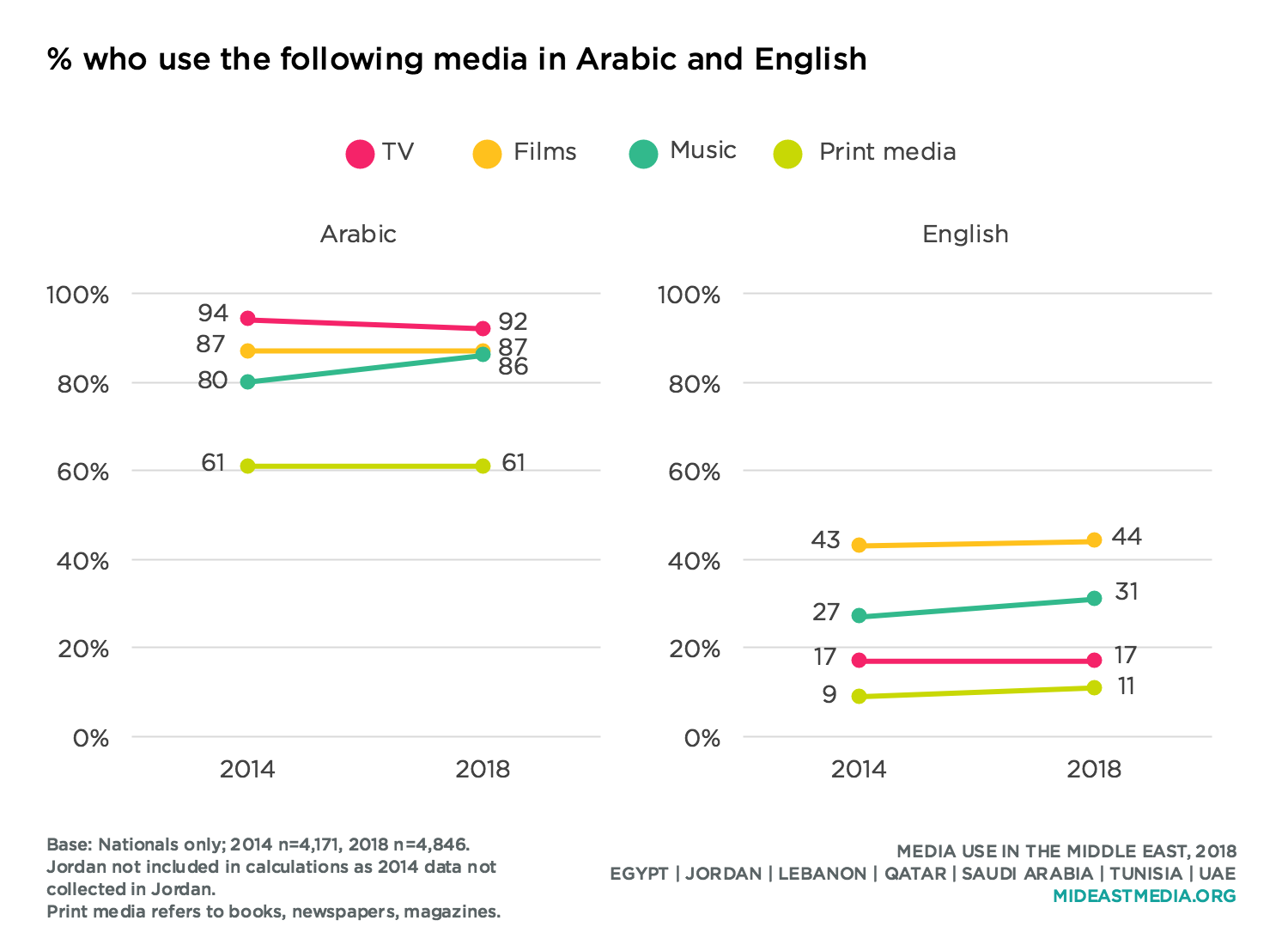

While media platform preferences are changing, the languages Arab nationals use to access media have not changed much. Between eight and nine in 10 nationals access Arabic-language TV, music, and film content—roughly the same proportion as in 2014. Around four in 10 nationals watch films in English, a third listen to music in English, and nearly one in five watch English-language TV, fractions all roughly the same as in 2014.

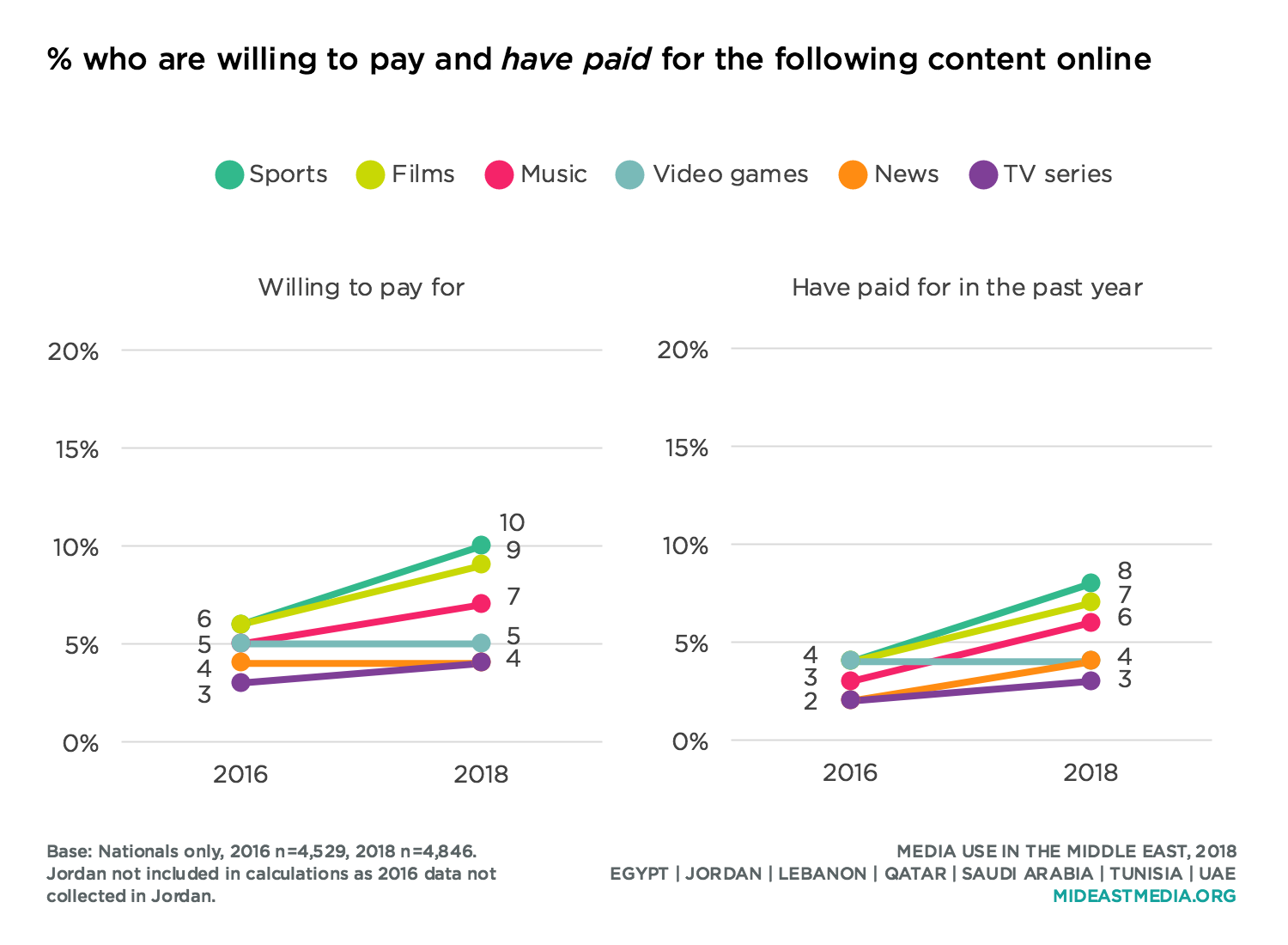

A small but growing portion of nationals are either willing to pay or have paid for online content in the past year, but figures depend on the type of content. Close to 10% of nationals in 2018 said they are willing to pay or have paid for sports, films, and to a lesser degree music content online; willingness to pay for video games, news, and TV series have remained low since 2016.

Most nationals have shared or commented online about some topic in the past month, and this figure has increased sharply since 2014 (any content: 28% in 2014 vs. 54% in 2016 vs. 62% in 2018). Nationals are most likely to share or comment on online videos—one third say they have done so in the past month—and about one in five or more have posted about music, news, and sports (34% online videos, 24% music, 19% news, 19% sports). Fewer nationals posted about films, ads, or TV programs in the past month (10% films, 9% ads, 6% TV programs).

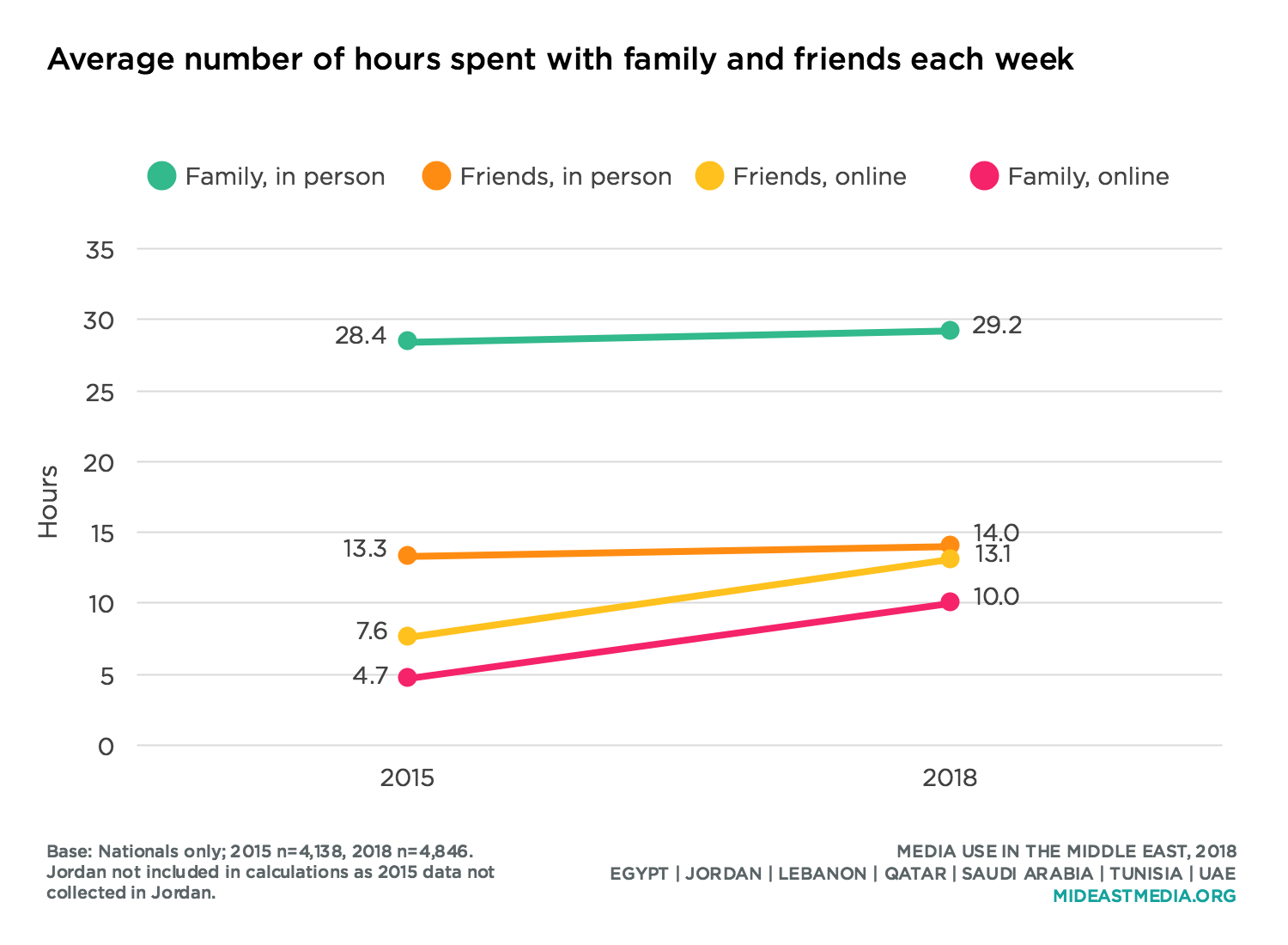

Even as both smartphone and internet penetration have soared in Arab countries in the last several years, the amounts of time Arab nationals say they spend with family and friends in-person each week has changed little since 2015 (29 hours family, 14 hours friends). Still, Arab nationals are communicating more with both friends and relatives online. The average amount of time spent each week online with friends and family each rose by five hours since 2015 (online friends: 8 hours 2015 vs. 13 hours 2018; online family: 5 hours vs. 10 hours).

Men and women spend equal time online with friends and family: about 12 hours per week online with friends and 9 to 10 hours online with family. Men, however, average five more hours per week in-person with friends, and women spend six to seven more hours each week in-person with family (face-to-face—friends: 16 hours men vs. 12 hours women; family: 28 hours men vs. 35 hours women).

Perhaps not surprisingly, younger Arab nationals on average spend more time with friends, both in-person and online, than the oldest nationals (45+), who spend more time in-person with family. The youngest nationals (18-24) average five more hours face-to-face and eight more hours each week online with friends than those over 45 years old (face-to-face: 17 hours 18-24 year-olds vs. 12 hours 45+ year-olds; online: 16 hours 18-24 year-olds vs. 8 hours 45+ year-olds). The oldest nationals, however, spend more time in-person with family each week than do nationals under 25, by five hours, but spend about the same amount of time online each week with family (34 hours 45+ year-olds vs. 29 hours 18-24 year-olds; online: 8 hours 45+ year-olds vs. 9 hours 18-24 year-olds).

Media Use Goes Digital

Mohamed Zayani, Georgetown University in Qatar

Although TV remains a dominant mass medium and an important source of entertainment for Arabs, TV viewership continues to decline in the Middle East as other forms of media engagement are gaining ground. This decline means that more people are spending more time on the internet as it becomes more integrated into their daily lives. These changes are due not just to internet penetration and mobile adoption trends, but also to the introduction of international streaming platforms, which constitute a growing threat to TV’s ability to maintain its market share. Online streaming is booming as it offers more choice in programming to wired Arab consumers at competitive prices. Emerging partnerships between international media companies and regional Arab media entertainment companies have further enhanced the ability of streaming services to attract niche audiences and to tailor media products to Middle East market needs and expectations.

Notably, the data here also reveal that changes in media consumption habits have not affected the users’ language preferences—Arabic remains the preferred language for national Arabs in their media consumption. However, it is useful to closely consider these socially favorable answers regarding language preferences. While the preference for Arabic-language use may not have changed much, media and entertainment products increasingly defy the binary distinction between Arabic and English. For example, if we consider some music genres that are being widely consumed by Arab youth, content often consists of a blend of cultures, such that popular Western tunes are incorporated into Arabic songs. The popularity of these hybrid music genres suggests that while Arabic is consistently the preferred language when it comes to entertainment media, the Arabic language content that is being accessed is changing. The above-noted increase in accessing entertainment media on digital platforms rather than TV will likely lead to an increase in the consumption of hybrid-language content, as well. In other words, media platform preferences may have more substantial cultural effects than the year-over-year consistency of Arabic language preferences suggested by the data.

By and large, digitization has had a larger effect on the platforms people use to access content than on the actual demand for Arabic content. This is evident in the greater demand for regional Arabic language streaming services than for global ones. For example, Shahid, which specifically targets Arab users with its rich repertoire of Arabic entertainment content, is far more widely used than international streaming services like Netflix. That said, international content is increasingly finding its way to regional streaming services through agreements and partnerships with industry players who are eying a market share in the Middle East’s growing subscription video market.

These findings need to be qualified by taking into consideration issues that go beyond content. For example, socioeconomic variables are important to note as demand for video streaming services in the Gulf region, with its superior ICT infrastructure capability and higher per capita income, is substantially higher than it is in other Arab countries covered by the survey. Equally noteworthy are widespread piracy issues as the number of users streaming videos illegally is rife and growing at an increasing rate. Significantly, while the apparent aversion to paid content the survey reveals accentuates the disruptive effect of piracy, it also tells us much about the disposition of telecommunication companies to adapt to shifting user needs and adjust to evolving consumer trends that are altered by digitality. Increasingly, telecom companies are offering bundles at competitive prices that cater to the growing demand for data and content consumption.

The survey data also suggest that ICT-induced changes are unfolding within a continuum of cultural practices. Better access to the internet and widespread use of smartphones have dramatically increased online activities and virtual communication in the Middle East and North Africa region, but have not necessarily undermined traditional forms of communication or modes of sociality. Online interactions are not making real-world interactions obsolete, which is tantamount to saying that online socialization is no substitute for real life socialization. The consistency of the survey findings tells us much about the ways in which people in the region have not only adapted fast-changing technological developments to social values and cultural practices, but also how users negotiate relationships in the digital era—though it is important to highlight that the real and the virtual world are not two separate spheres, as online and offline communication tend to overlap.