Most Qataris—nearly nine in 10—say news media in their country are credible. This represents a 26 percentage-point increase in perceived credibility in just one year, and is well above the average of nationals from other countries (Qatar: 62% in 2017 vs. 88% in 2018; all other nationals: 39% in 2018). Only a minority of Qataris, however, say news media can report news in Qatar without interference from officials.

.png)

The 2017 data were collected in Qatar and all other countries (except Egypt) before the Saudi-led blockade of Qatar began, while 2018 data were collected in Qatar and other countries just over a year after the blockade began. While many factors likely contribute to dramatic changes in Qatar in attitudes about free speech, the Saudi blockade (in which the UAE and Egypt are also participating), is likely among those factors, if not the primary indicator.

At the same time, more Qataris also say they feel comfortable speaking out about politics. In 2018, about four times as many Qataris say it is safe for people to discuss politics online as said so in 2017. Qataris are now far more likely than nationals from other Arab countries to say they feel comfortable expressing their views about politics. Additionally, about half of Qataris say people should be free to criticize governments on the internet, which is twice the rate observed for Qatar nationals in 2017.

.png)

Far fewer Qataris than other Arab nationals are worried about governments or companies checking what they do online. Only 16% of Qataris express concerns about either type of surveillance—half to a third of the rates of nationals in other countries (government: 30% Tunisia, 44% Lebanon, 47% UAE, 58% KSA, question not asked in Jordan or Egypt; companies: 29% Tunisia, 41% Jordan, 47% Lebanon, 50% Egypt, 61% UAE, 62% KSA).

Additionally, fewer than half of Qataris and Tunisians want more internet regulation in their country, much lower than the rates in other countries (45% Qatar and 43% Tunisia vs. 60% KSA, 62% Egypt, 66% UAE, 84% Lebanon; question not asked in Jordan).

Qataris and Egyptians, though, more than other nationals, support censorship of entertainment content. Most Qataris say deleting scenes from films or TV programs is appropriate if some people find them offensive (84% Qatar, 89% Egypt, 78% KSA, 75% Jordan, 75% UAE, 65% Lebanon, 45% Tunisia) and a majority also says that government oversight helps production of quality entertainment (84% Qatar, 83% UAE, 76% Egypt, 74% KSA, 67% Lebanon, 35% Tunisia, question not asked in Jordan).

Compared to 2016, however, Qataris are more evenly divided concerning who is responsible for blocking or avoiding objectionable content. The percentage of Qataris who think it is mostly the responsibility of government to block objectionable content, rather than mostly the individual’s responsibility to avoid such content, dropped by 8 percentage points since 2016, while those who think the individual bears primary responsibility rose by 13 points (2016: 54% government’s responsibility, 40% individual’s responsibility; 2018: 46% government’s responsibility, 53% individual’s responsibility).

Qataris reported changing attitudes about culture between 2016 and 2018. Fewer Qataris now than in 2016 say more should be done to preserve cultural traditions—62%, down from 81%. While most Qataris say their culture should do more to integrate with modern society, that figure nonetheless dropped from 79% to 65% between 2016 and 2018.

That said, most Qataris have consistently said that more entertainment should be based on their culture and history (83% in 2014, 80% in 2016, 82% in 2018), larger percentages than those among other Arab nationals—though a sentiment that is shared by Egyptians (83%).

Perhaps as a show of national pride, Qataris are significantly more likely than in 2017 to say films and TV programs from their country are good for morality—a 22 percentage-point increase—while at the same time they are less likely to say films and TV content from the Arab world in general are good for morality—10 points less than 2017. Qataris and Tunisians are the only nationals who were less likely in 2018 than 2017 to say Arab world films are good for morality, and to put the Arab world and Hollywood/US films and TV programming at parity with regard to morality.

.png)

The month of Ramadan is a time when some daily schedules and behaviors in Muslim countries change, and this is also the case in Qatar. Many Qataris say that during Ramadan they spend more time consuming religious media and more time consuming entertainment content with family (do more during Ramadan: 81% consume religious content, 61% consume entertainment with family). This appears to come at the expense of other activities, most of which Qataris do less of during Ramadan (do less during Ramadan: 74% listen to music offline, 73% listen to music online, 73% watch films on TV, 73% watch films online, 70% watch films at the cinema).

The proportion of Qataris who use the internet grew from eight in 10 in 2014 to nearly everyone in 2018 (78% vs. 99%, respectively). This is consistent with internet use in other Arab Gulf countries under study, though multiple middle-income countries studied also have internet penetration above 85%.

Online streaming is common in Qatar, as well as Saudi Arabia and the UAE. However, both Netflix and Shahid are used by nearly equivalent numbers of Qataris, whereas Shahid holds a significant advantage over Netflix in other countries studied.

.png)

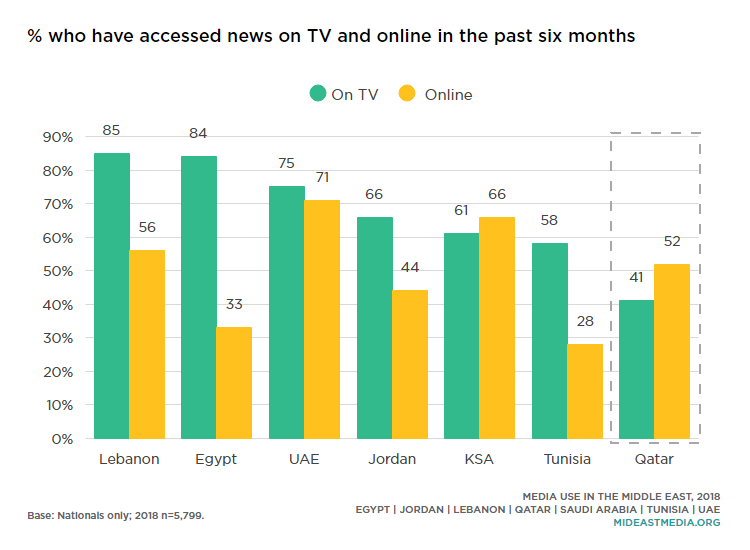

At least half of Qataris accessed news, music, and films online in the past six months, and the increase for music and films since 2016 was sharp (music: 33% in 2016 vs. 58% in 2018: films: 38% vs. 58%, news: 56% vs. 52%). One-third of Qataris have watched TV programs online in the past six months, nearly double the rate in 2016 (14% in 2016 vs. 33% in 2018). Qataris and Saudis are the only nationals who were more likely to have accessed news online than on TV in the previous six months.

Qataris and Saudis are also the nationals most likely to have paid for online sports content in the past year—double or more the rates in UAE, Tunisia, Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon—though the share that paid for sports in either country did not exceed 17%.

.png)

Just one-quarter of Qataris watch TV programs once a day or more—a lower rate than in any other country (26% Qatar vs. 43% Jordan, 43% Lebanon, 49% UAE, 58% Tunisia, 61% Egypt, 63% KSA). Qataris also are the nationals least likely to play games on a phone at least once a day. Less TV viewing and game playing among Qataris may help explain the at-times higher news consumption among that population, or the comparably larger amounts of time Qataris spend communicating with friends and family online and in person..

.png)

A firm majority of Qataris say they exercise or play sports at least once a week—almost six in 10—a figure that is higher only for Emiratis (58% Qatar, 69% UAE, 45% KSA, 37% Tunisia, 32% Lebanon, 24% Jordan, 9% Egypt).

Well over half of Qataris (as well as Emiratis) say they go to the cinema at least once a month, a much higher rate than that among nationals in other countries, one-third of whom or fewer go to the cinema with the same frequency.

.png)

Unlike other Arab nationals, most of whom watch films from their own country, Qataris and Jordanians are twice as likely to watch films from other Arab countries as from their own country (own country: 26% Qatar, 25% Jordan vs. 51% Tunisia, 55% UAE, 68% KSA, 70% Lebanon, 96% Egypt; other Arab countries: 55% Qatar, 66% KSA, 66% UAE, 64% Lebanon, 49% Jordan, 31% Tunisia, 14% Egypt). Qataris are, however, increasingly likely to watch films in Arabic (68% in 2014 vs. 82% in 2018).

Qataris spend significant amounts of time each week with family and friends, both online and in person: 29 hours each week in person and 15 hours a week online with family. Qataris also spend an average of 15 hours in person with friends each week and 22 hours online with friends. No other nationals in the countries studied spend more time online with family or friends.

.png)

About four in 10 Qataris play video games, more than Egyptians, Jordanians and Lebanese, but less than Saudis and Emiratis (43% Qatar, 72% KSA, 62% UAE, 42% Tunisia, 35% Lebanon, 21% Jordan, 19% Egypt). Among those who play video games, Qataris are equally like to play with others as alone, while other nationals spend more of their gaming time playing alone.

.png)

Qataris estimate that more of the online video they consume is news rather than entertainment (48% news/information, 38% entertainment), and are the only nationals who so estimate that a plurality of the online video they consume is news.

.png)

Qataris, along with Jordanians, are more likely than other Arab nationals to identify news as a favorite genre of both TV and online video (news is a top three favorite TV genre: 42% Qatar, 44% Jordan, 32% Egypt, 30% Tunisia, 29% UAE, 27% Lebanon, 25% KSA; top three favorite online genres: 30% Qatar, 36% Jordan, 31% UAE. 27% KSA, 24% Egypt, 21% Lebanon, 19% Tunisia).

While seven in 10 Arab nationals surveyed check news online at all, the rate in Qatar is much higher, nine in 10, similar to rates in Saudi Arabia and the UAE and much higher than in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia (90% Qatar, 95% UAE, 85% KSA, 72% Lebanon, 70% Jordan, 66% Tunisia, 45% Egypt).

Qataris, along with Emiratis, lead countries surveyed in the percentage of the population that has earned a college degree, and significantly more Qataris now than in 2014 say they finished a four-year degree program. The figure for Qataris is second to the UAE, but close to or more than double the rates in the other countries.

.png)

Freedom of Expression Behind the Blockade

Mehran Kamrava, Georgetown University in Qatar

Close to two years after the eruption of what is commonly referred to in Qatar as “the crisis” with its three neighbors, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE, along with Egypt, the consequences of the diplomatic dispute are clearly reflected in this and other similar public opinion surveys. In particular, Qatari attitudes about two politically salient issues – freedom of expression and the health of Qatari culture – appear to be profoundly impacted by the diplomatic and geopolitical predicament in which the country has found itself since June 2017, when the quartet broke off diplomatic relations with Qatar, accused it of sponsoring terrorism and interfering in their domestic affairs, and imposed sanctions on trade and other exchanges with the country. In the ensuing months, the political animosity between the parties involved has only become more intense and in-depth. Not surprisingly, there have been significant changes in Qatari politics as a result, and, more consequentially, to Qataris’ relationship with their political leaders and their assumptions about state policies.

Popular assumptions about censorship and the scope of permissible expression are especially revealing in this regard. Most notably, there has been a noticeable rise in Qatari perceptions of freedom of speech and a commensurate decrease of concern about online surveillance. An astounding percentage of Qataris – no less than 88 percent – believe that the news media in their country is credible. This is despite the fact that a significant majority of the country’s expatriate population, 61 percent, continues to remain skeptical about the veracity of the news they hear.

Interestingly, whereas in other Arab countries people feel generally less secure to criticize the government or to say whatever is on their mind online, significantly more Qataris felt free to express themselves online in 2018 as compared to 2019 (72% in 2018 as opposed to 23 percent in 2017). Equally telling is the fact that four times as many Qataris feel more comfortable expressing their views online as was the case in 2017. Similarly, there has been a steady increase in Qataris’ perceptions of openness and freedom of expression. In fact, by 2018, far fewer Qataris, 16 percent, worry about online surveillance by the government or by companies than in any of the other countries in the survey.

In the absence of discernible changes to state policy in regards to online surveillance and permissible political expression, this indicates an increasing narrowing of the state-society gap, especially insofar as Qatari political culture is concerned. Especially in comparison to other political leaders in the region, and from among the ruling families, the Al-Thanis have always enjoyed greater popularity among their subjects. Since 2017, however, Qataris feel particularly closer to their political leaders, seeing the state in general and the person of Sheikh Tamim in particular as responsible for carefully navigating Qatar out of what could well have been crushing sanctions by bigger and more powerful neighbors.

Similar changes appear to be occurring in the cultural arena, whereby fewer Qataris as compared to the past worry about preserving cultural traditions (62% in 2018 compared to 81% in 2016). In a small state where the national population comprises around only 12% of the total, assumptions about threats to culture and identity are often rooted in fears of being overwhelmed by foreign expatriates in one’s own country. Since 2017, however, many non-Qataris living in the country have been vocal in their loyalty to and solidarity with the country, therefore narrowing some of the social and cultural chasms that have always existed between the national and non-national populations.

This is not to imply that Qataris have lost interest in their own culture and history. Since 2014, in fact, more than 80% of Qataris have consistently believed that more of the entertainment they consume should be based on Qatari culture and history (82% in 2018). Only Egyptians are similarly concerned about cultural preservation through entertainment.

Perceptions of freedom of expression and lack of online surveillance do not necessarily translate to support for unrestricted expression in the entertainment field. In line with many others in the survey, an overwhelming majority of Qataris, 84 percent, support the censorship of entertainment content and the deletion of objectionable scenes and content from films or TV programs. Slightly more than half of Qataris believe it is the responsibility of individuals instead of the government to regulate entertainment content.

The June 2017 diplomatic dispute between Qatar and its neighbors has clearly had multiple consequences for political and social life in Qatar, as well as for the country’s economy. In the economic realm, Qatari policymakers made up for their overnight loss of the country’s overwhelming reliance on imports from the UAE’s Jebel Ali port by quickly reestablishing alternative suppliers and supply chains for essential goods and exports. By any standard what Qatar has accomplished economically has been impressive.

But perhaps even more noteworthy, and most likely longer lasting, have been developments in Qatari politics and culture. Qataris nationals have long had a relatively harmonious relationship with their rulers, with most of the political turmoil the country has witnessed having been confined to struggles for power and influence within the ruling family. But, as the data presented here clearly indicates, that relatively harmonious relationship has assumed new dimensions, with deeper levels of popular trust toward the state and greater feelings of freedom of expression. How long these sentiments will last if and when Qatar’s dispute with its neighbors is settled, and in what direction assumptions about politics and culture are likely to develop in the post-dispute era, are questions that only time can answer.