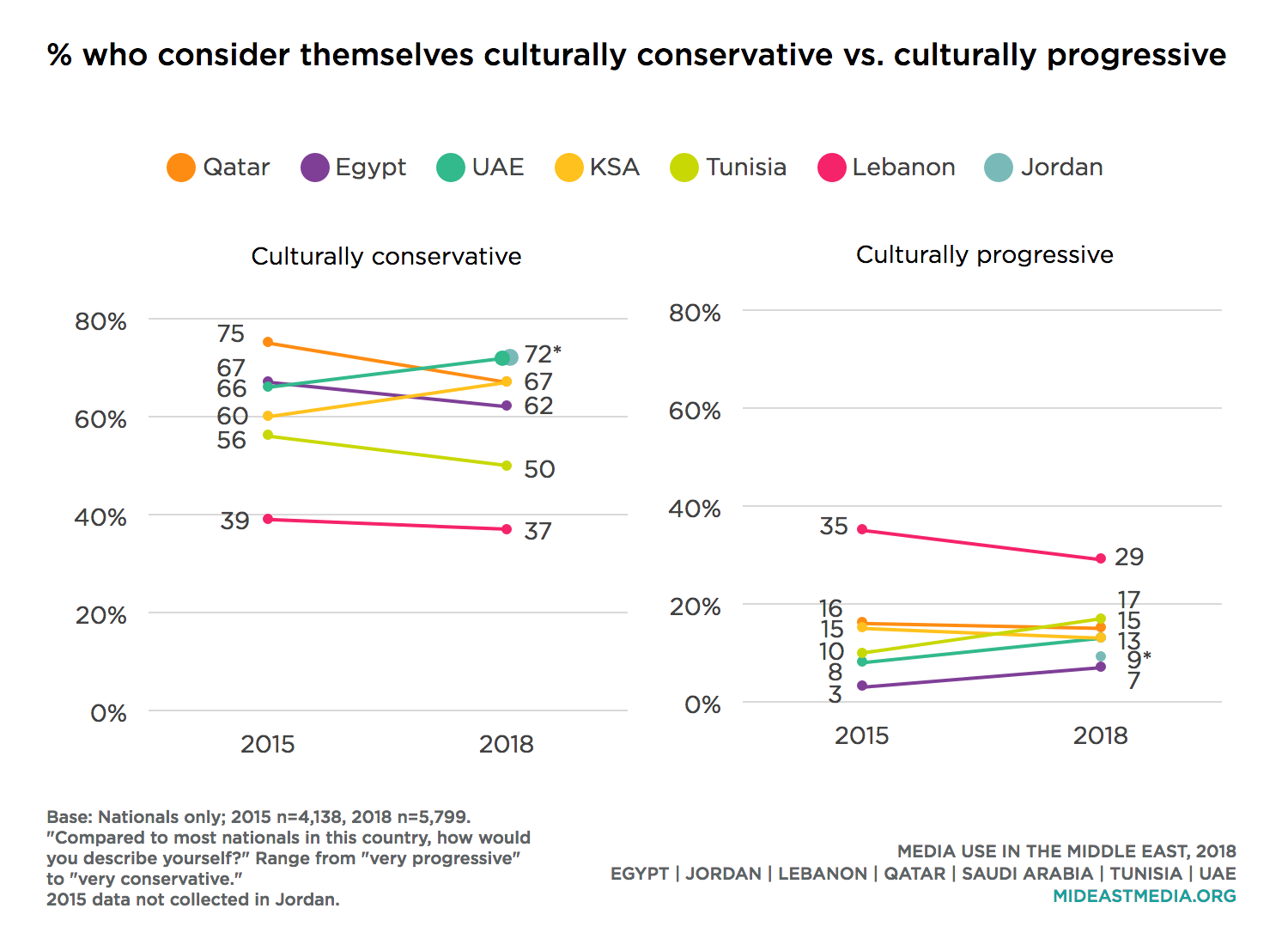

Most nationals in all countries except Lebanon self-identify as culturally conservative. Seven in 10 Jordanians, Qataris, and Saudis—and six in 10 Egyptians—say they are either somewhat or very culturally conservative compared to other nationals in their country. Lebanese self-identify as culturally conservative, progressive, or neither with near equivalent frequency.

From 2017 to 2018 the proportion of cultural conservatives grew in five of the seven surveyed countries. This proportion grew somewhat in Jordan and by 20 percentage points or more in Egypt, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. This could indicate that nationals in these countries are either becoming more conservative or nationals feel their compatriots are more comparatively liberal, or some combination of both.

Older Arab nationals are more likely to consider themselves culturally conservative than younger Arab nationals, but even half of the youngest respondents describe themselves as conservative (52% 18-24 years old, 56% 25-34, 59% 35-44, 66% 45+). That said, nearly three times as many of the youngest cohort as the oldest age group identify as progressive (21% 18-24 years old, 18% 25-34, 12% 35-44, 8% 45+).

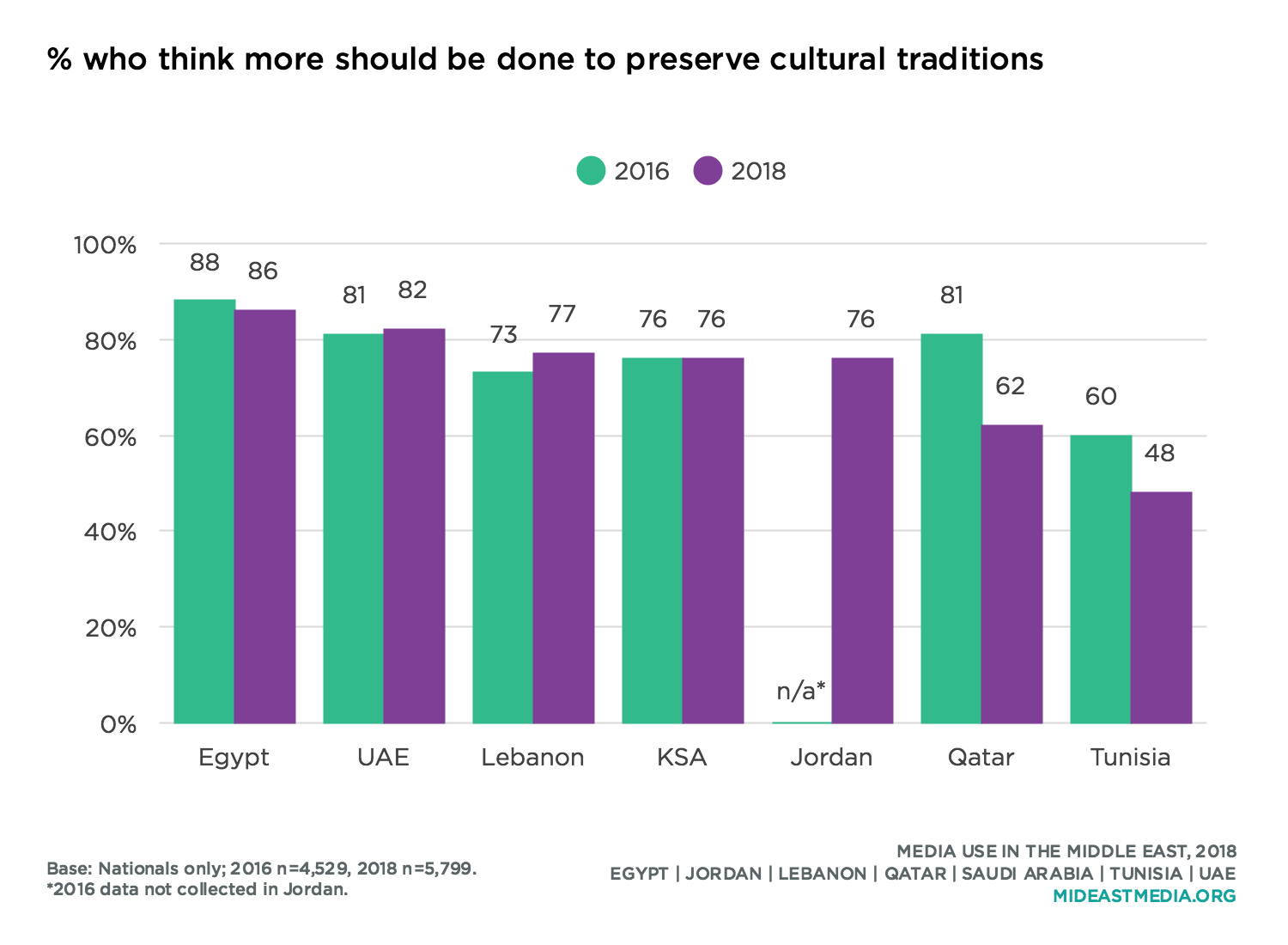

At once, Arab nationals want greater preservation of their own culture while also saying their culture should do more to embrace modernity. Large majorities of nationals in five countries, at least three-fourths, say more should be done to preserve cultural traditions.

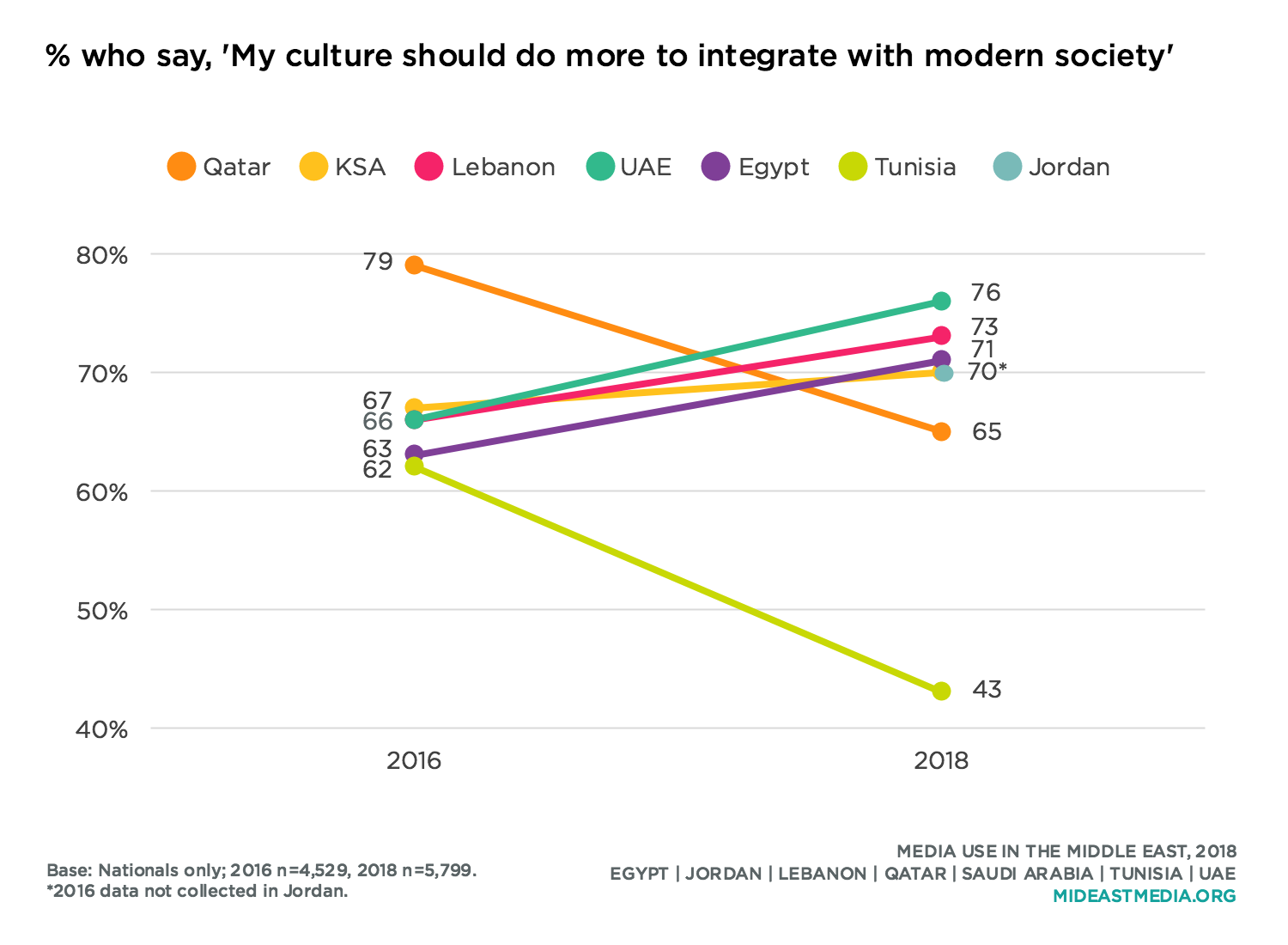

At least two-thirds of nationals in all countries except Tunisia say their culture should do more to integrate with modern society. Still, agreement with this statement dropped significantly since 2016 among Qataris and Tunisians, while increasing among Egyptians, Lebanese, and Emiratis.

Conservatives and progressives do not differ much in attitudes about preserving cultural traditions or increasing integrating with modernity. Between six and seven in 10 of both conservatives and progressives say more should be done to preserve cultural traditions, and also that their culture should do more to integrate with modern society (preserve cultural traditions: conservative 74%, progressive 64%; integrate with modern society: conservative 64%, progressive 67%). Fewer of the least educated nationals (primary school or less) favor more cultural integration with modernity, but still more than half agree (55%).

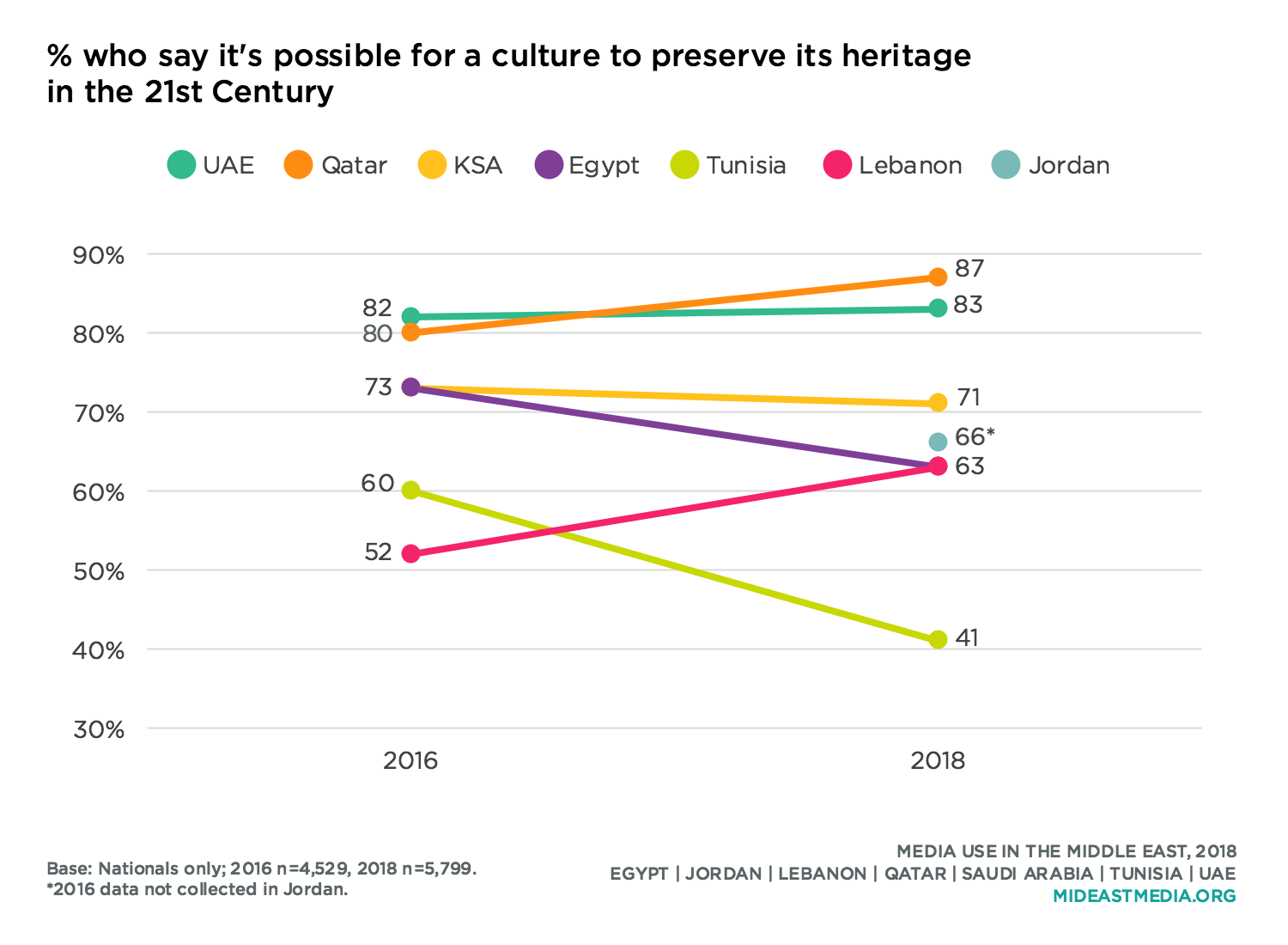

More than half of nationals in all countries say preserving culture in modern times is possible, and agreement is highest in Qatar and the UAE. Tunisia is a lone outlier, as just four in 10 agree—a significant decline since 2016.

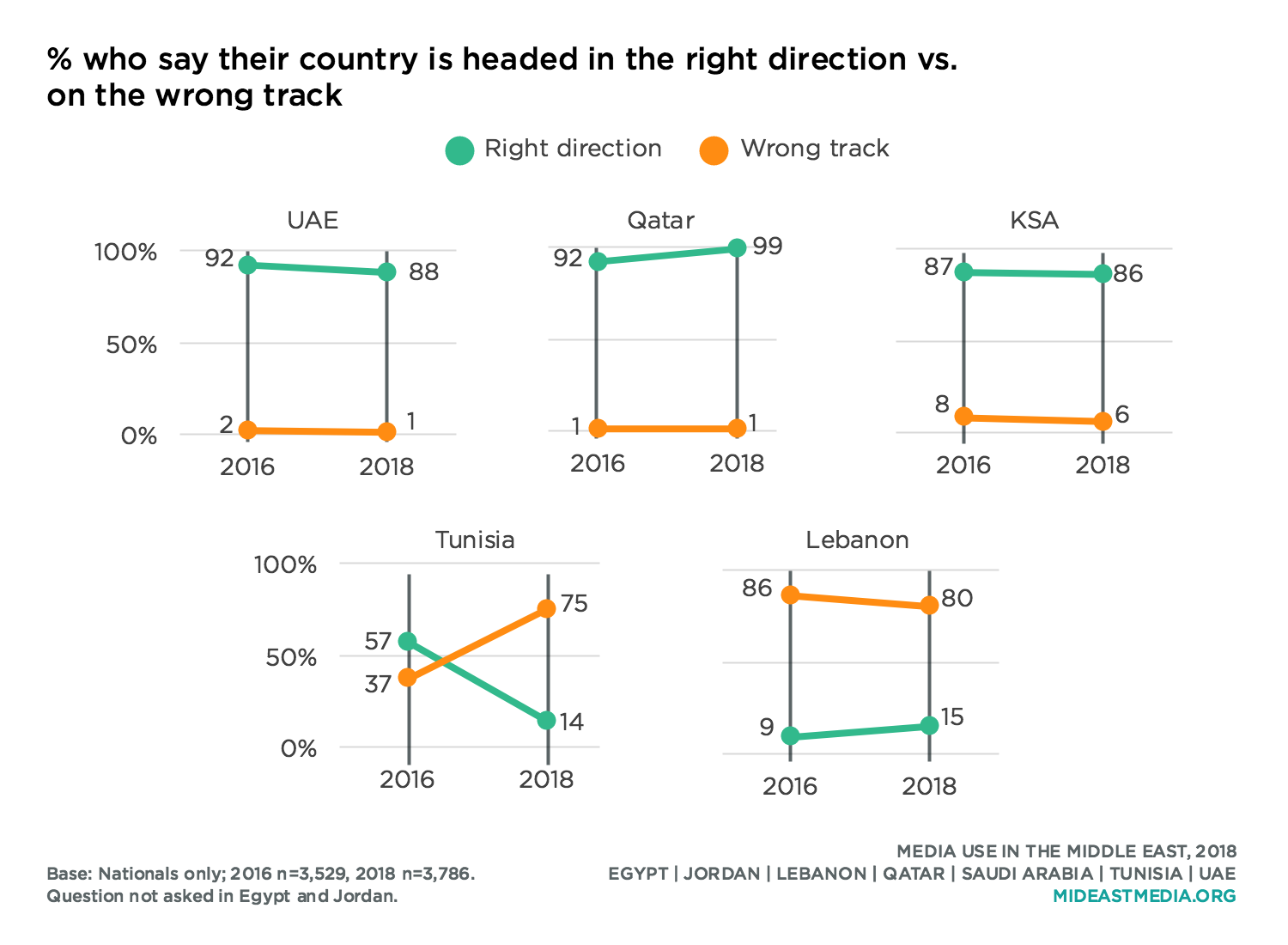

Clear majorities of Emiratis, Saudis, and Qataris say their respective country is headed in the right direction, figures that have changed little in each country since 2013. Conversely, approximately eight in 10 Lebanese and Tunisians say their country is on the wrong track. This question was not permitted by officials in Egypt or Jordan.

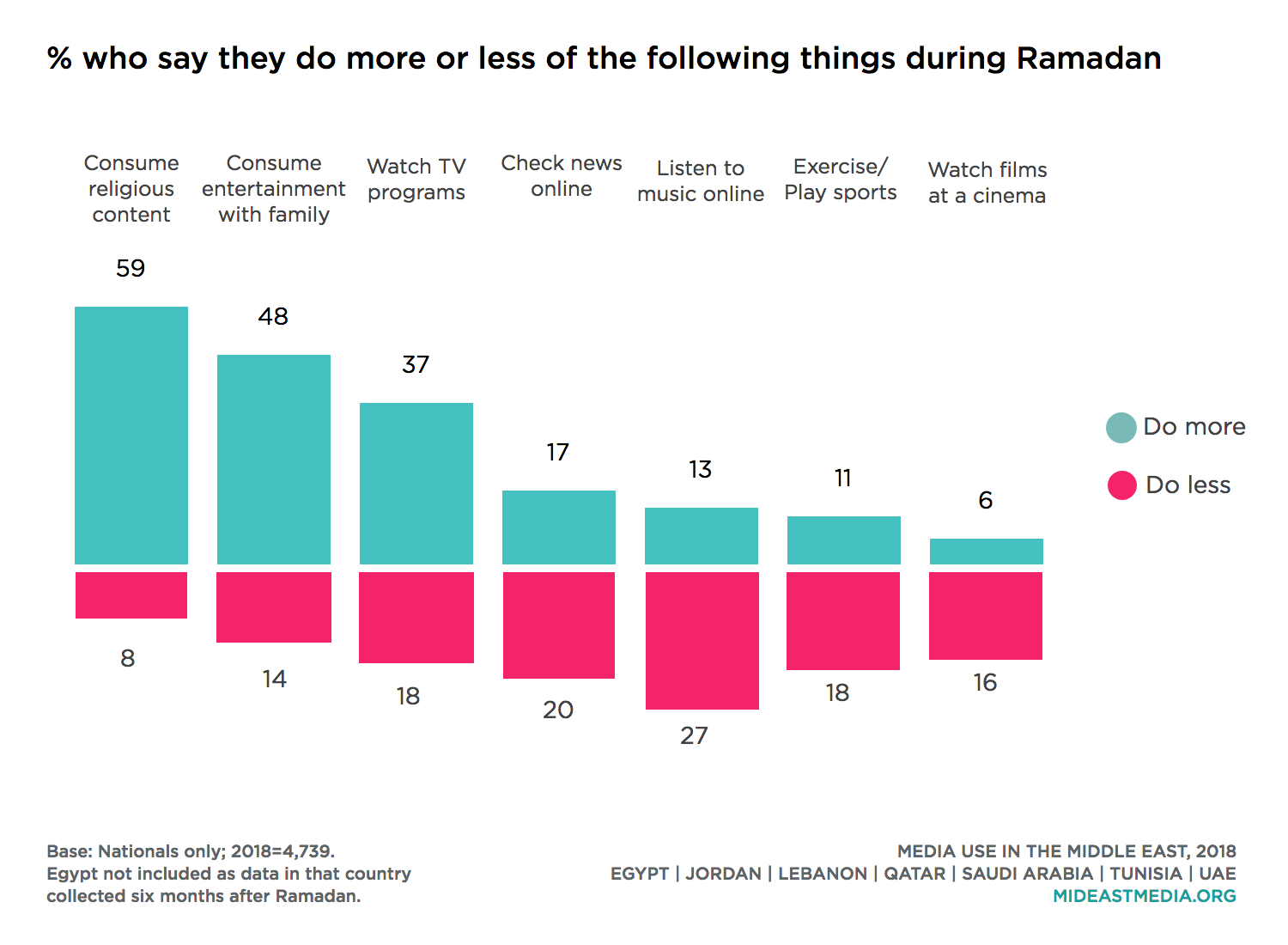

During Ramadan, content preferences shift, as a majority of Arab nationals report accessing more religious content, and close to half consume more entertainment content with family. Nearly four in 10 Arab nationals increase their TV use.

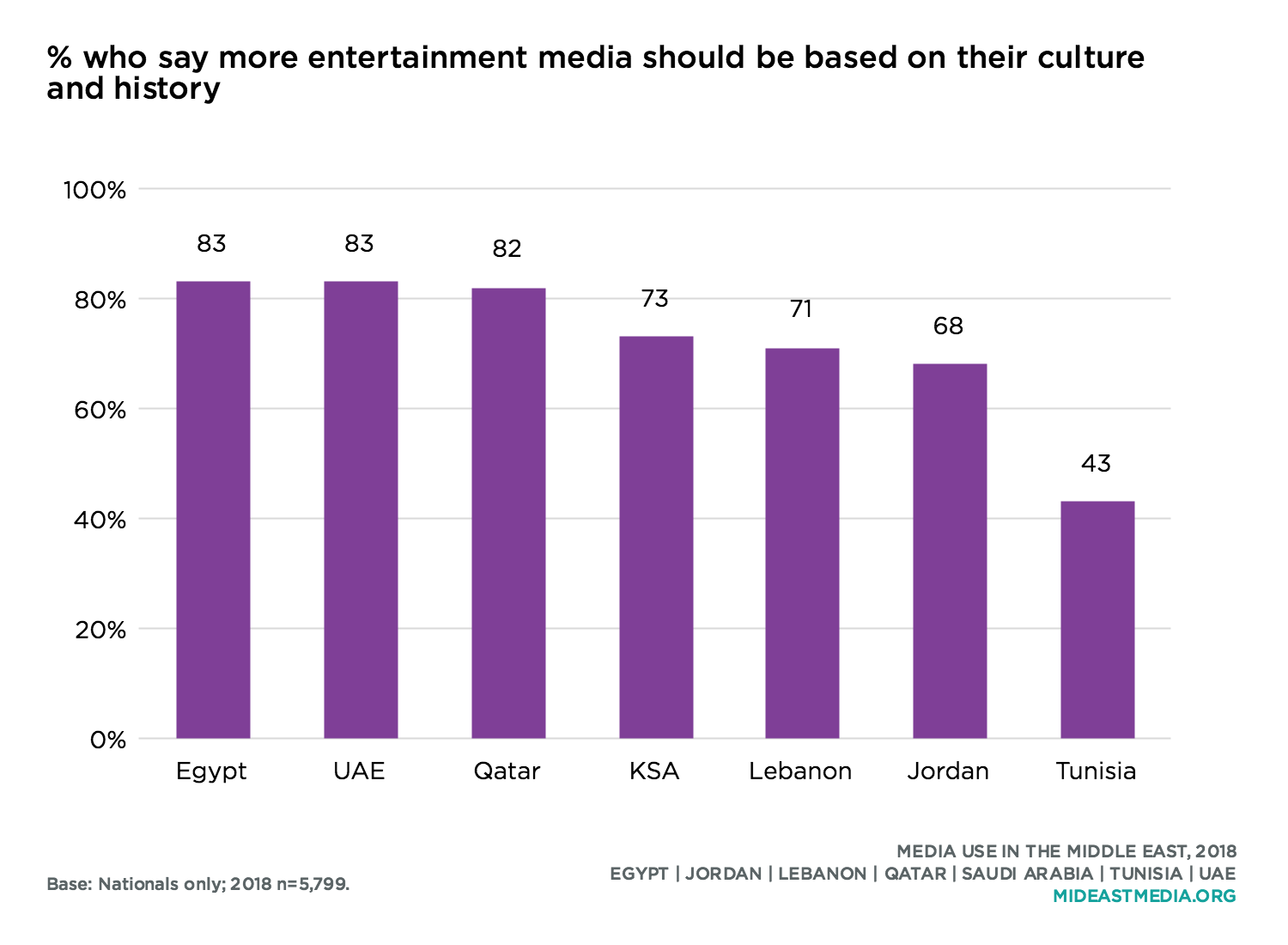

Concerning entertainment attitudes, at least two-thirds of Arab nationals, again except for Tunisia, say more entertainment media should be based on their history and culture. Egyptians, Emiratis, and Qataris are the most likely to agree.

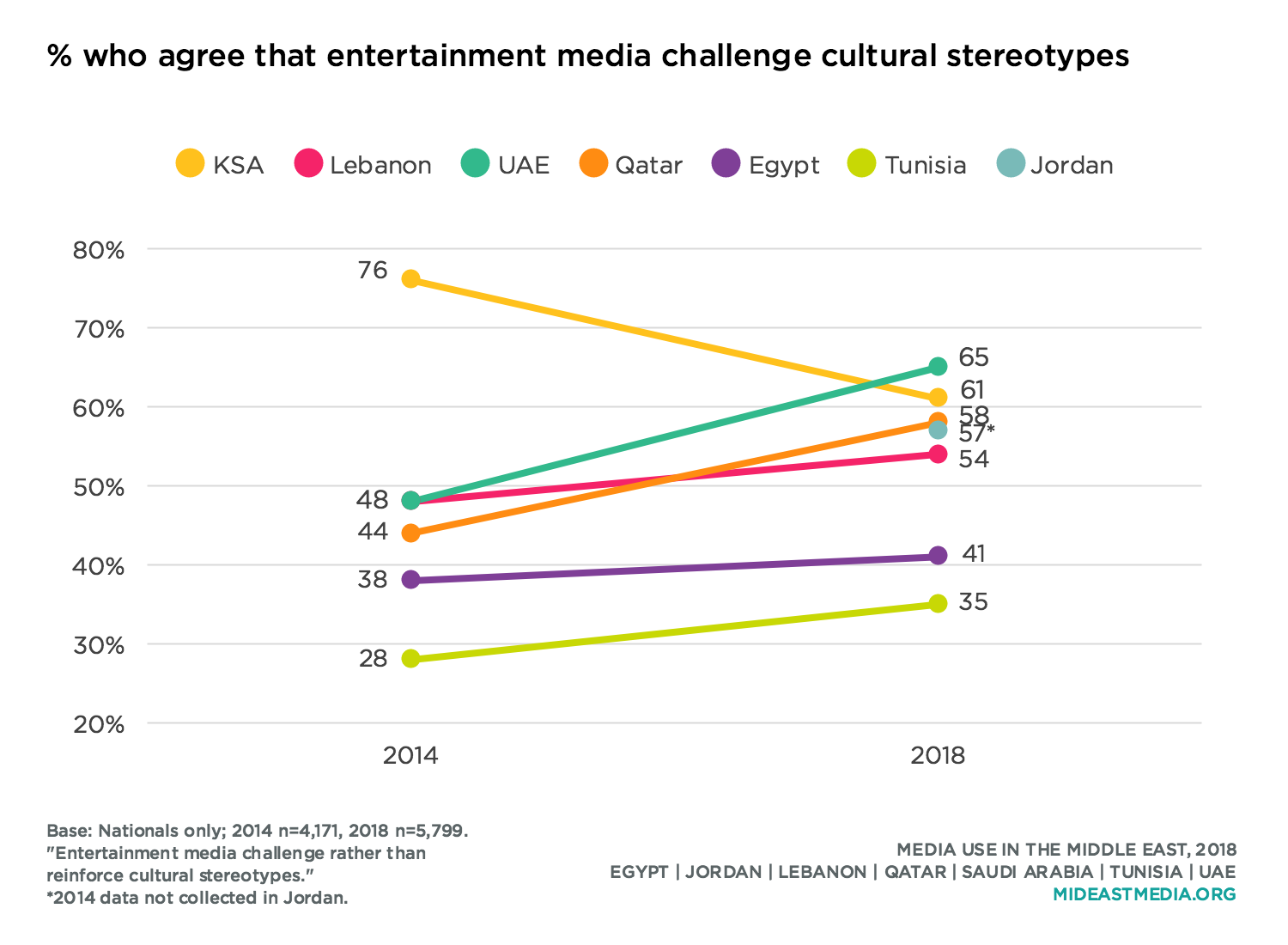

Additionally, majorities of nationals in most countries think entertainment media challenge cultural stereotypes, a more common sentiment in all countries over the past two years except Egypt and Tunisia, where fewer than half of nationals agree, a decline in agreement between 2016 and 2018.

About half of both conservatives and progressives say entertainment media challenge cultural stereotypes (50% conservative vs. 48% progressive).

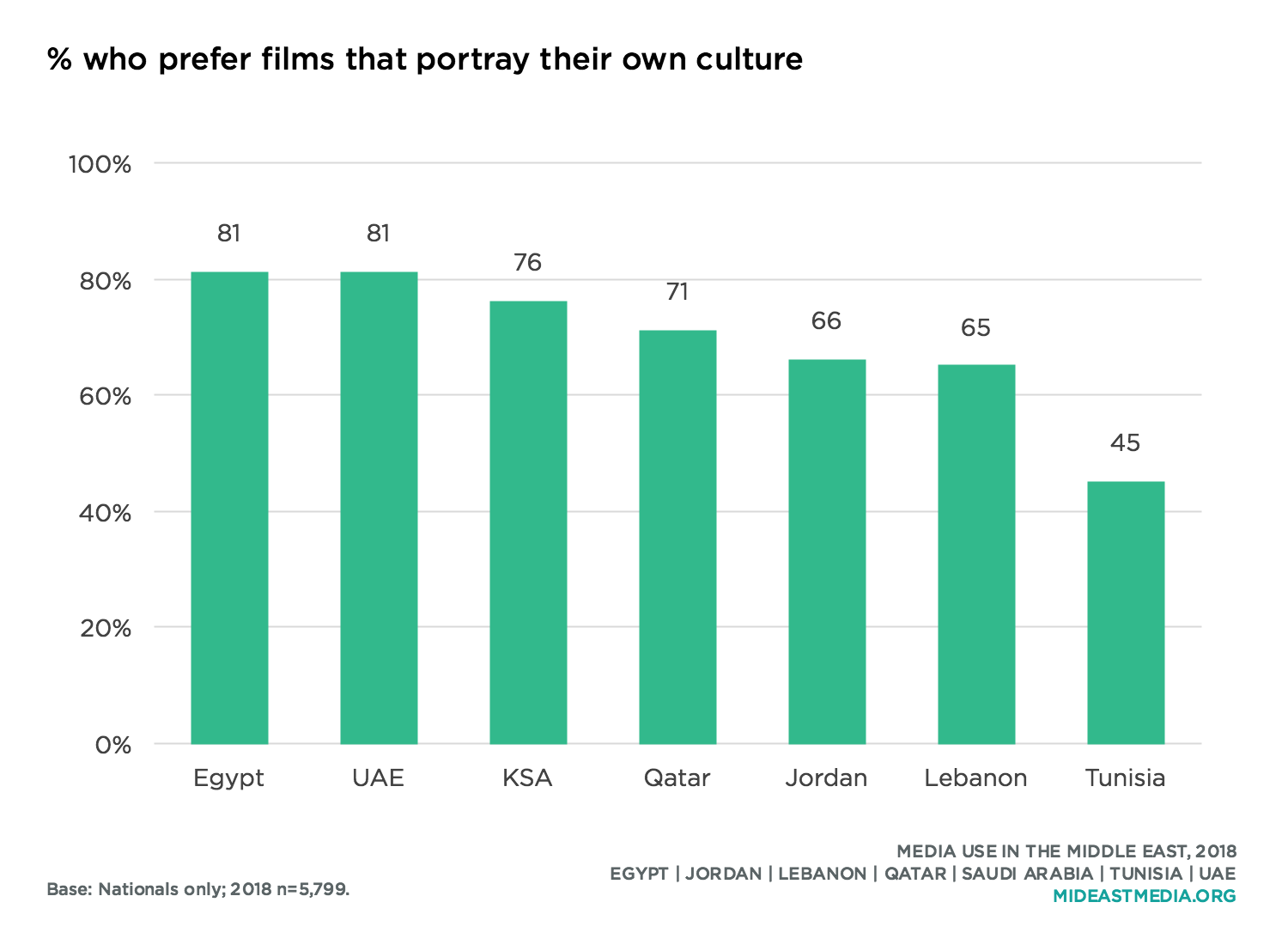

Most nationals in all countries except Tunisia say they prefer watching films about their own culture, and that films are an important source of information about one’s own culture.

While progressives are a bit less likely than conservatives to prefer films about their own culture, more progressives than conservatives say films are an important source of information about one’s culture (I prefer to watch films that portray my own culture: 70% conservative vs. 57% progressive; films are an important source of information about one’s own culture: 58% conservative vs. 64% progressive).

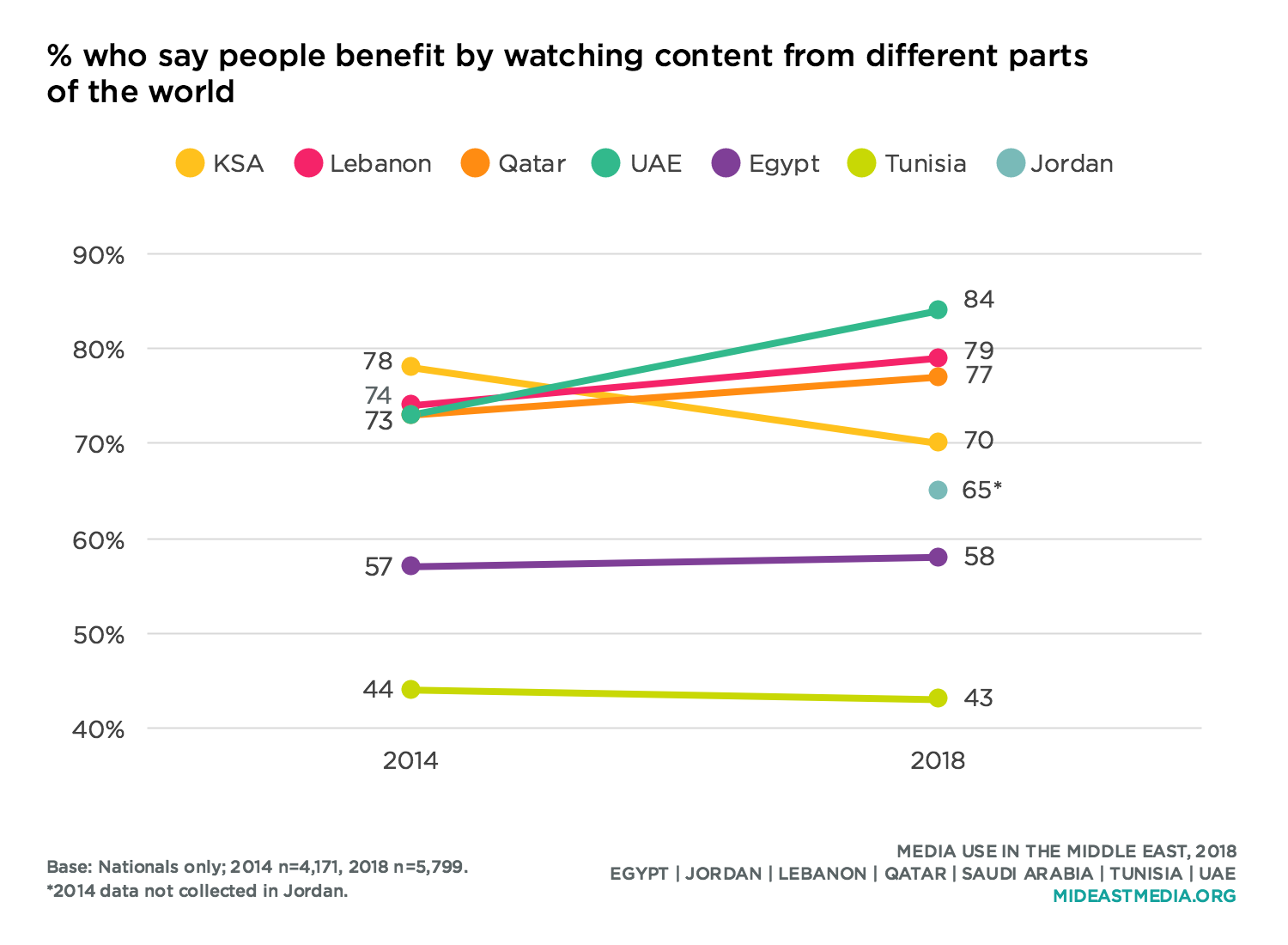

While Arab nationals prefer entertainment content about their own culture, most nationals in all countries also say people benefit from watching entertainment content from other parts of the world, including at least seven in 10 Emiratis, Lebanese, Saudis, and Qataris (Tunisia, at 43% agreement, is again the lone holdout).

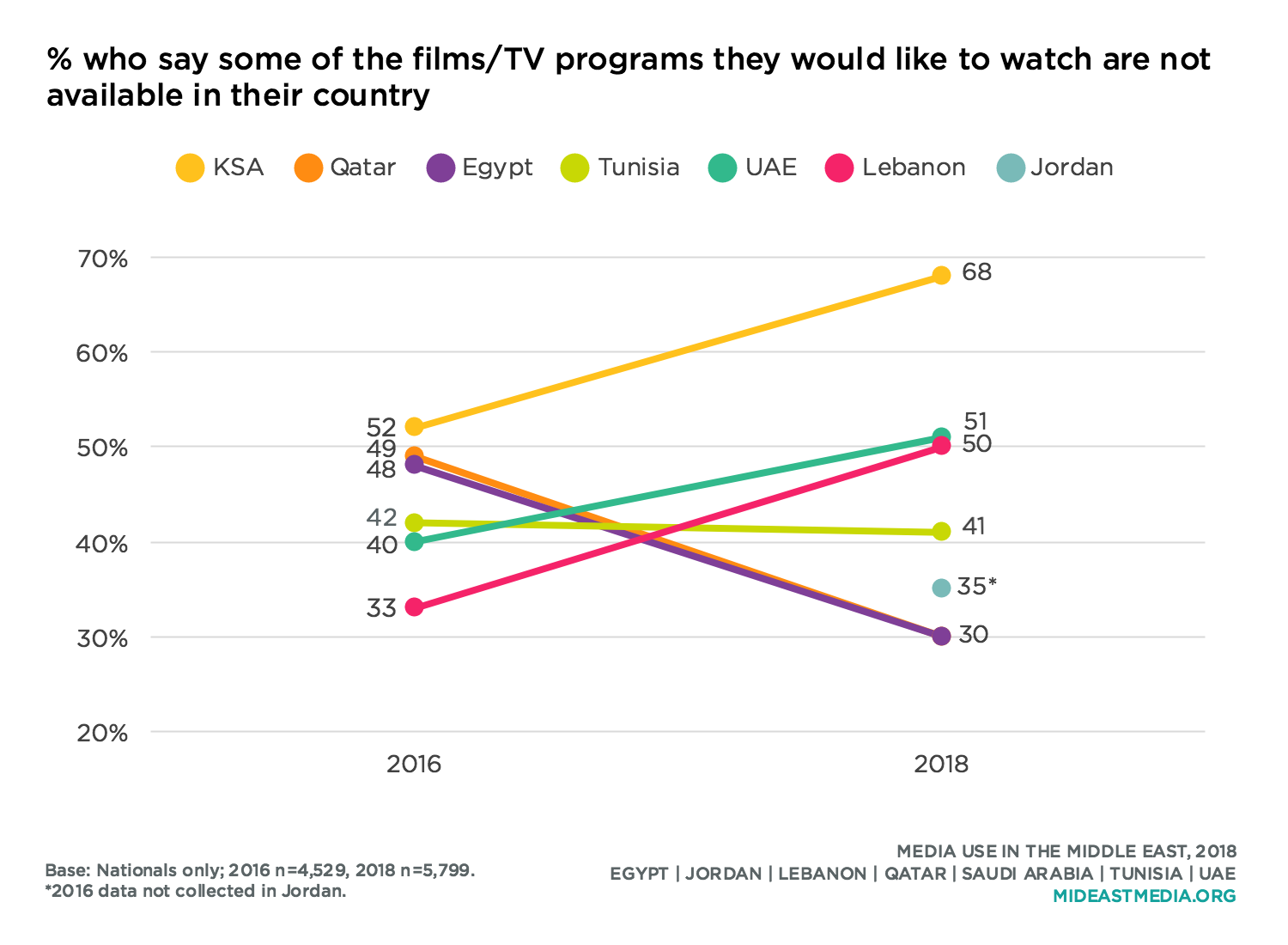

Growing percentages of Lebanese, Emiratis, and Saudis say some of the films and TV programs they would like to watch are not available in their country. The proportion of Qataris and Egyptians who agree with this statement dropped sharply since 2016.

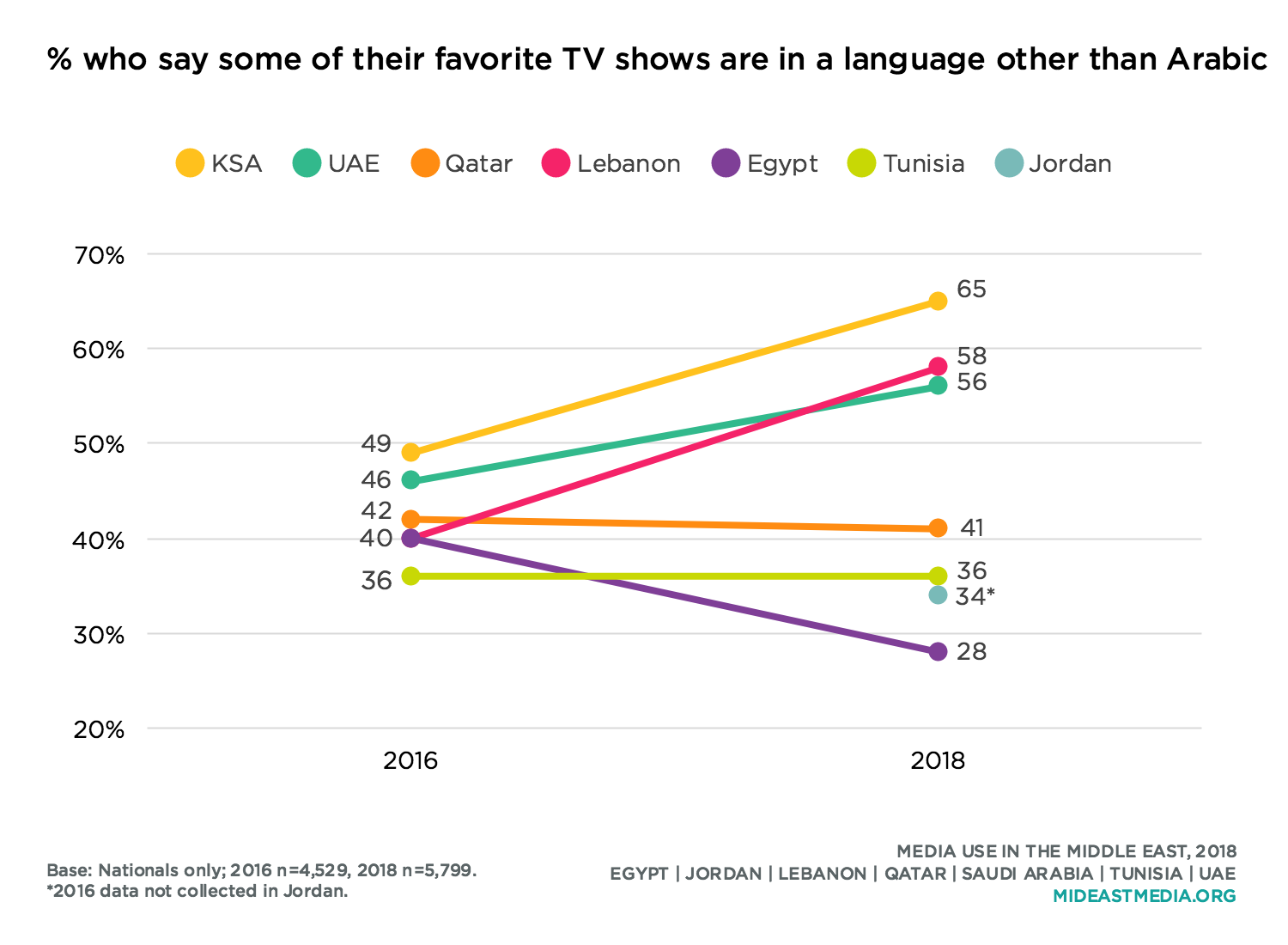

At least a third of nationals in each country say some of their favorite TV shows are in a language other than Arabic.This figure grew to over half of Emiratis and Lebanese, and to nearly two-thirds of Saudis, between 2016 and 2018. The one exception is Egypt, where fewer than three in 10 agree—a sharp decline from 2016.

Cultural progressives are more likely than cultural conservatives to say some of their favorite TV programming is in a language other than Arabic (54% progressive vs. 41% conservative).

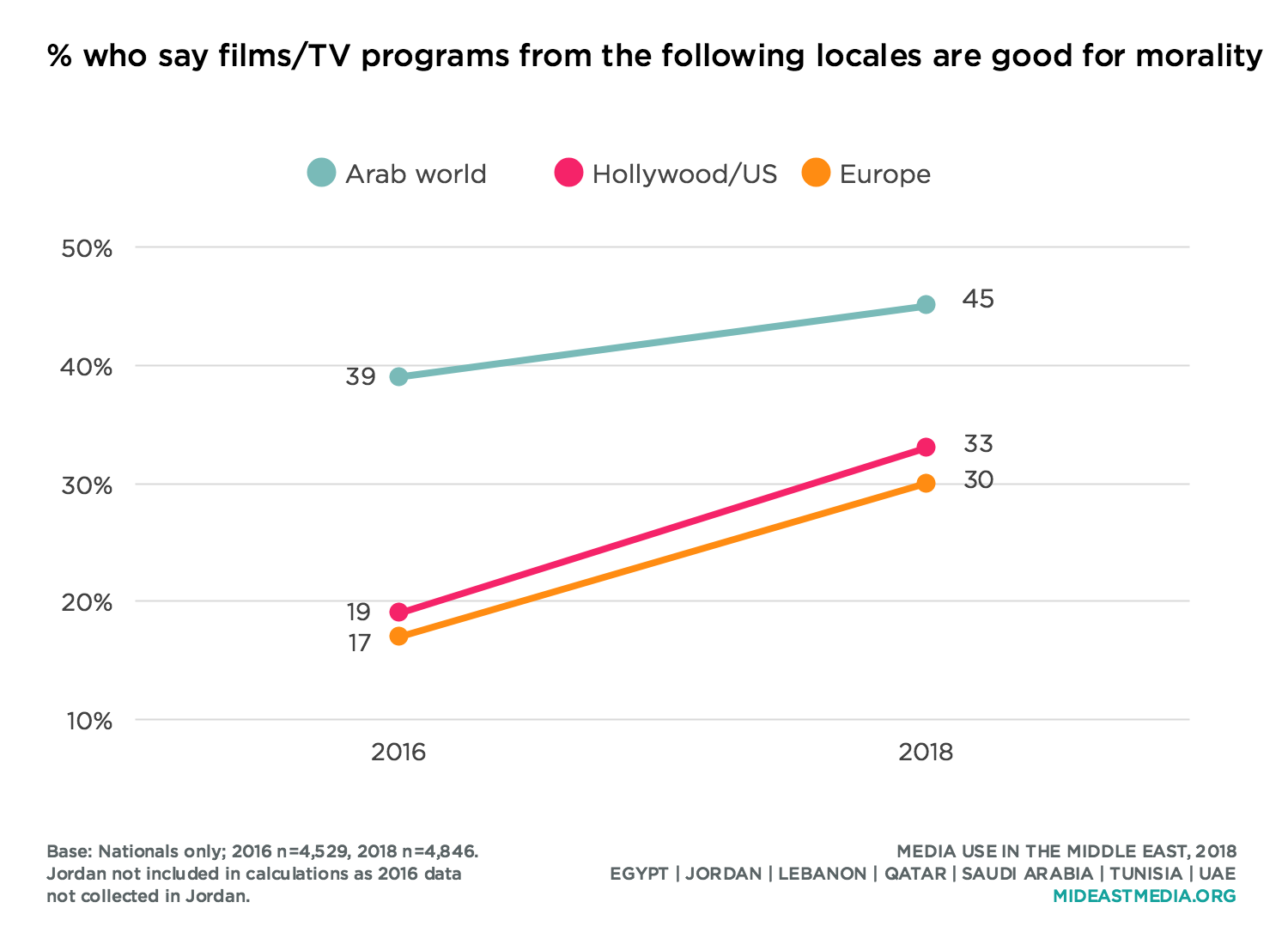

Arab nationals were significantly more likely in 2018 than in 2016 to say that films and TV from the U.S. and Europe are good for morality, while they only marginally more likely to say films and TV from Arab countries are good for morality. Still, in 2018, more nationals overall say that entertainment content from Arab countries is good for morality than say entertainment content from the U.S. bolsters morality. Egyptians stand out as being far more likely—three times more—to say entertainment from the U.S. and Europe are bad for morality that good for morality, representing a significant increase since 2016 in the number of Egyptians who say film and TV from these countries are bad for morality,

Cultural conservatives are as likely as cultural progressives to say Arab entertainment content is good for morality, but are less likely than progressives to say content from the U.S. and Europe are good for morality (films and TV from the Arab world in general are good for morality: 46% progressive vs. 46% conservative; from Hollywood/US: 42% progressive vs. 30% conservative; from Europe: 39% progressive vs. 27% conservative).

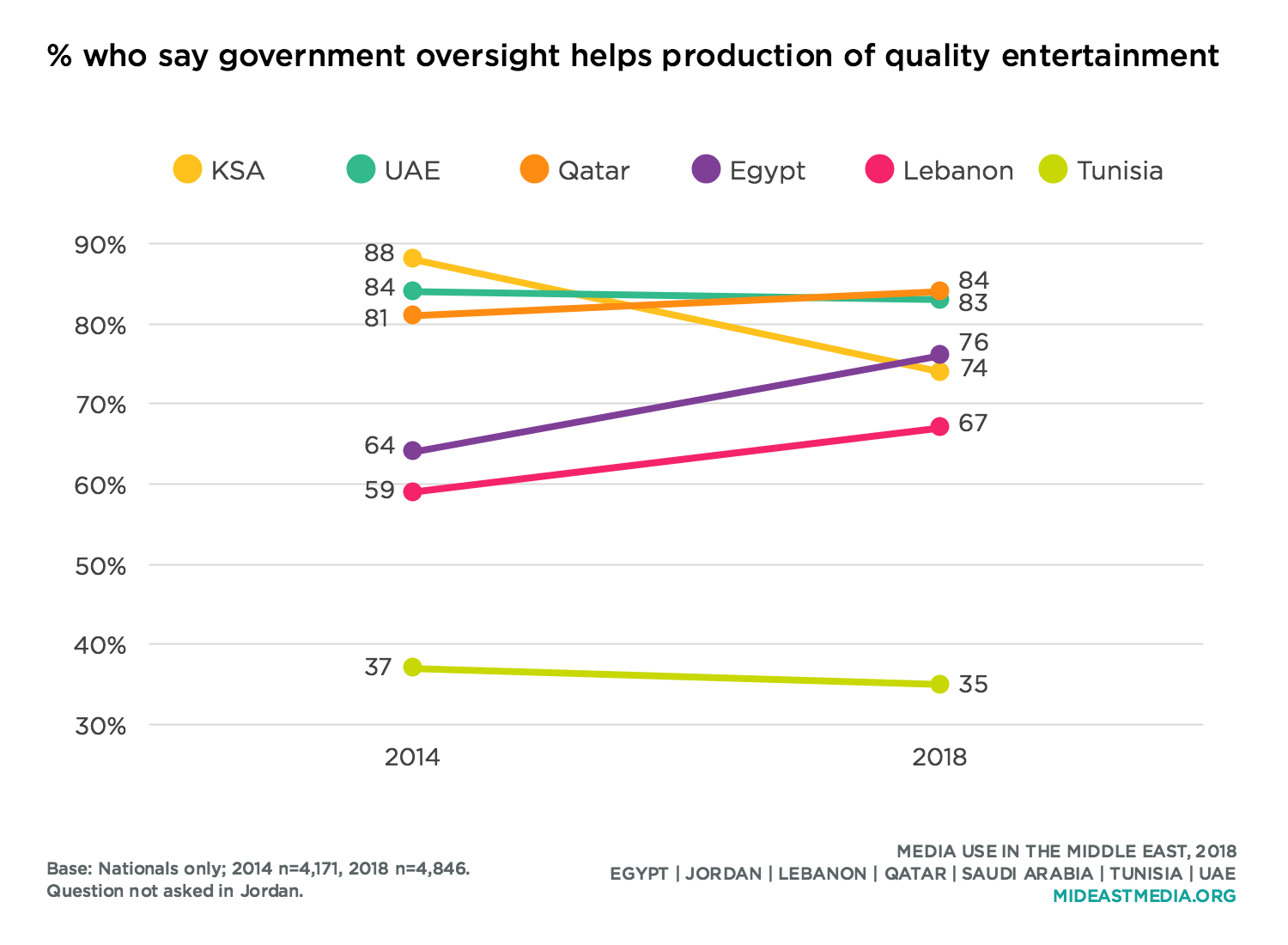

At the same time, nationals in all countries except Tunisia tend to agree that government oversight improves the quality of entertainment. Similar numbers of cultural conservatives and progressives agree (52% conservative, 53% progressive).

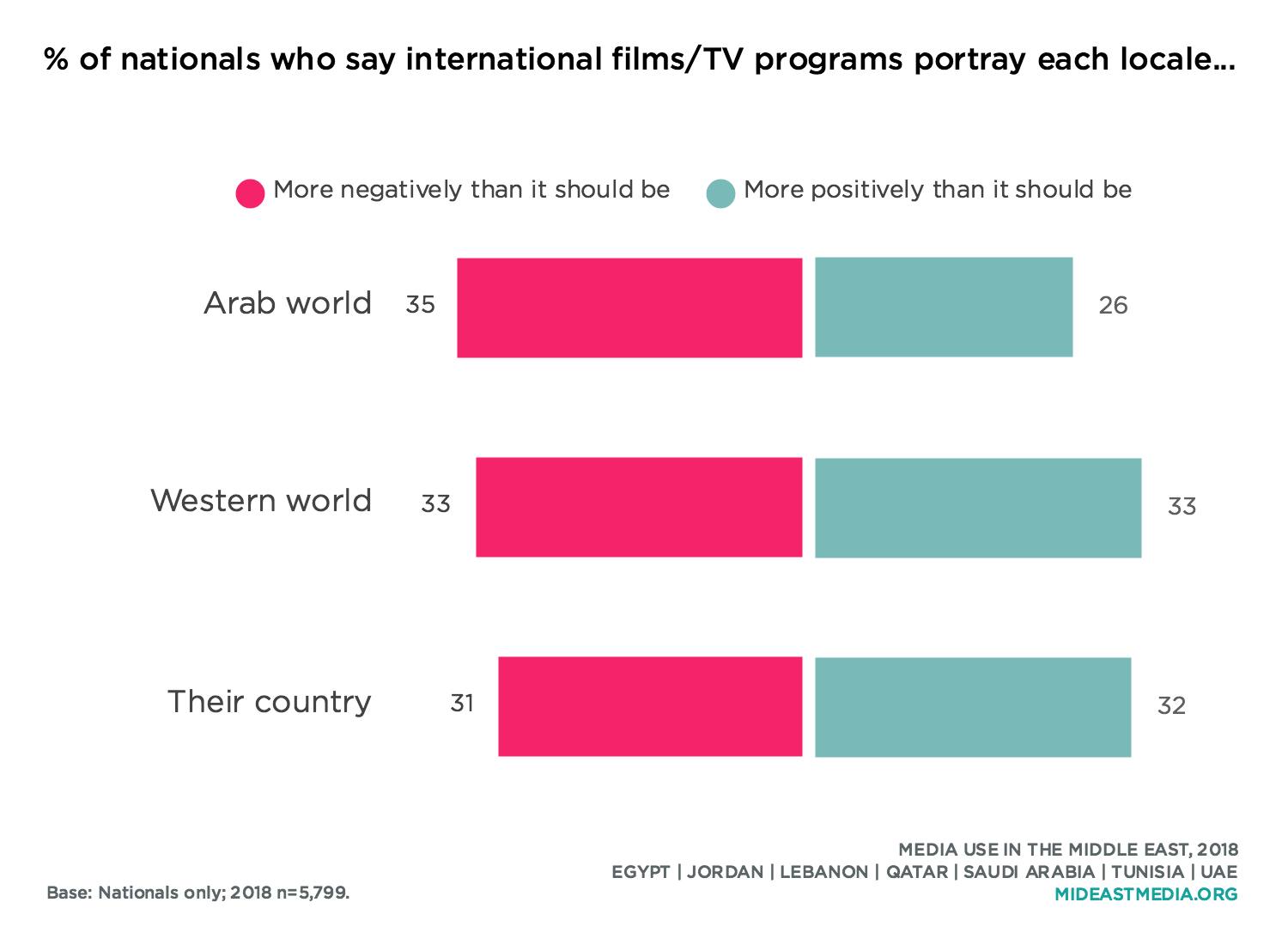

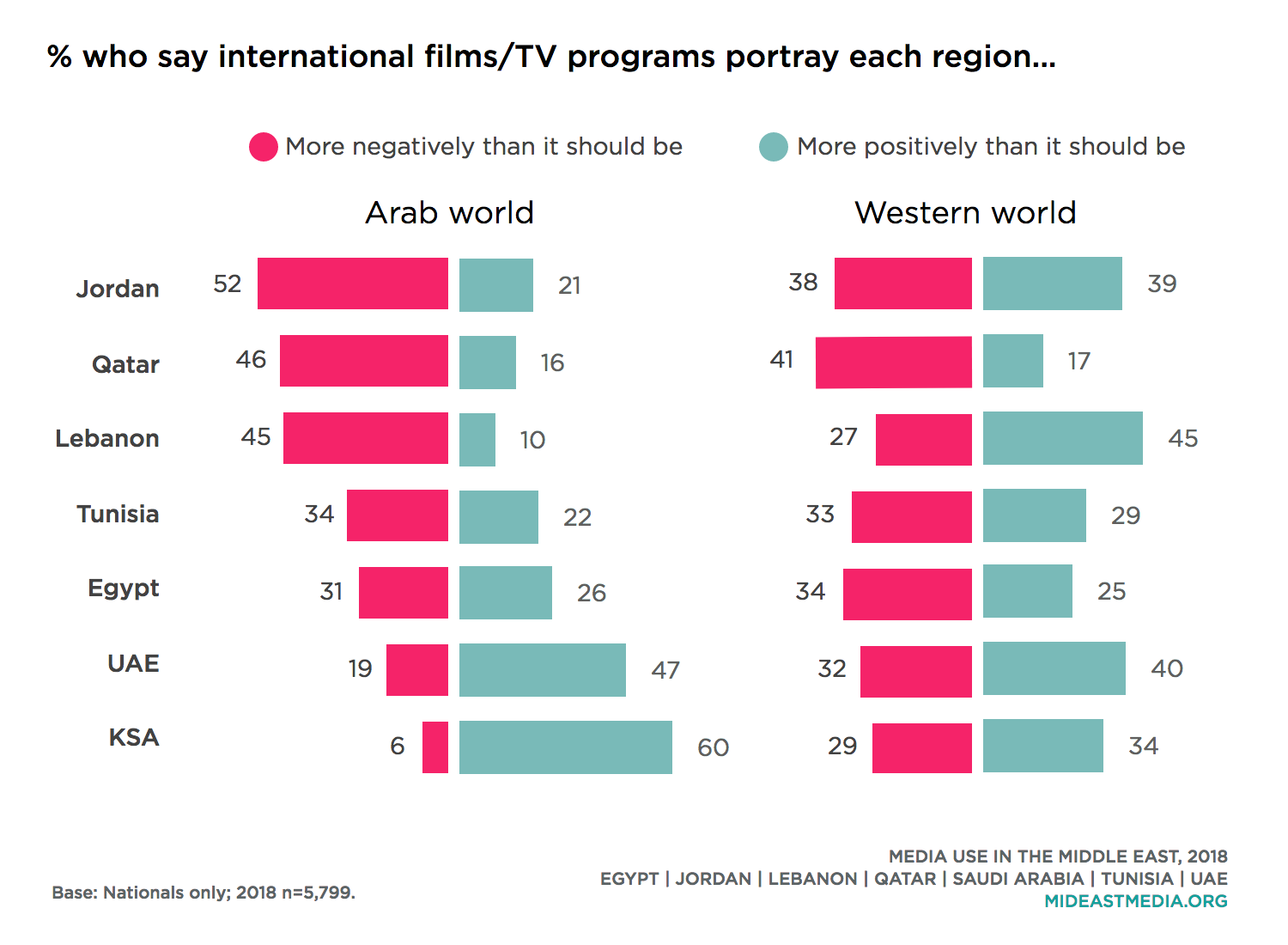

When asked about the portrayal of various locales in international film and TV, there is some variation across countries. Nationals in Arab Gulf countries are more likely to say their country is portrayed too positively than to say it it is represented too negatively, while the opposite is true for nationals from the middle income countries—Lebanon, Tunisia, Egypt—who are more likely to say their country is portrayed too negatively.

Saudis and Emiratis are more likely than other nationals to say international TV and film portray the Arab world positively, rather than negatively, by more than two to one. Perceptions of how they portray the Western world are fairly evenly split in all countries except in Qatar and Egypt, where nationals more often say the Western world is portrayed too negatively, and in Lebanon, more nationals say the Western world is portrayed too positively.

Nationals with more education are more likely than less-educated nationals to say both their own country and the Western world are portrayed more positively than they should be (country of residence: 24% primary or less, 28% intermediate, 33% secondary, 34% university or more; Western world: 18% primary or less, 30% intermediate, 35% secondary, 39% university or more).

Entertainment Media in an Era of Media Crackdowns

Shibley Telhami, University of Maryland

A counter-revolution has been in full force in many parts of the Arab world in the past few years. Nowhere is this more visible than in the push back against free media, both traditional and digital. It’s true of course that media has always been either a political instrument or a target of rulers. But the push back that followed the Arab uprisings was more deliberate than ever: Rulers and the elites around them, who have survived or recovered from the revolutionary popular revolts that began in 2010, have concluded, not incorrectly, that the information revolution – a mixture of transnational satellite television stations, the internet, and social media – has been a key factor in unleashing the masses. Sure, the public grievances had deeper economic, political, and social roots of discontent, but nothing that had not been experienced in the past; the information revolution thus explains at least the timing of the uprisings, and why rulers were taken by surprise, unable to react quickly enough to mass protests. Not only has this revolution led to Arab public empowerment, but it was also instrumental in getting people out into the streets in threatening numbers, without the need to rely on traditional political and social organizations. Thus, given this common conclusion about the role of media, when it comes to news and to sharing political opinions freely, many parts of the Arab world are in the middle of a dark chapter that’s even darker than during the period preceding the Arab uprisings.

This, however, does not apply to entertainment, including Western entertainment. In part, entertainment has always been seen by rulers as something that distracted from politics and was thus less threatening. Moreover, many of the ruling elites in much of the Arab world see Islamists as a threat, at the same time that the latter tend to be more traditional and less welcoming of some forms of entertainment, including Western entertainment. The public has generally been receptive to more entertainment choices, including from the West. In this regard, the data here shed new light on this issue, particularly in mapping out change over time.

Broadly, even as most Arabs prefer watching films about their own culture, majorities in most countries say people benefit from watching entertainment content from other parts of the world; despite the finding that in all countries but Lebanon, majorities consider themselves culturally conservative. Strikingly, Arab nationals are more likely now than in 2016 to say films and Western TV programs are ‘good’ for morality. Still, there are results that require explanation.

Majorities in all but one country (Tunisia) say that people benefit from watching content from different parts of the world, but the biggest drop from 2014 to 2018 was in Saudi Arabia (from 78% to 70%). This period coincides with the rise of cultural and social liberalization steps undertaken by the Saudi government, which emphasized these dimensions of reform, even as it clamped down on political opposition and free speech. Some of these high-profile steps included opening movie theaters and hosting musical performances by international artists. One might thus expect that there would be some push back from conservatives, which may explain the drop. Similarly, Saudi Arabia is the only country with a noticeable drop in the number of people who say government oversight helps production of quality entertainment, from 88% in 2014 to 74% in 2018.

Asking if one’s country is headed in the right or wrong direction is a tough question, as this poses a potential challenge to authoritarian governments’ narratives, so public responses may be guarded. In Egypt and Jordan, this question was not even permitted. Overall, there has been little change from 2016 to 2018 in the perceptions of the direction that the country is moving, except in one case, Tunisia, where there was a sizable drop in the number of people who said their country is moving in the right direction, from 57% in 2016 to 14% in 2018. This is a striking finding.

Tunisia is where the Arab uprisings began and it has been seen by many, especially in the West, as the most successful case of the Arab uprisings. It has avoided large-scale violence, undergone open elections, put in place a constitution with liberal elements, and has had a more permissive environment for free speech and media than most other Arab countries. But a lot has changed in recent months. The internal political balance has shifted, and the government’s failure to improve the economy – especially for the very young people who spearheaded the initial uprisings – has led to new, widespread protests.

A month after former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled Tunisia, in February 2011, I flew to Tunis to participate in a special episode of the Doha Debates, even as public demonstrations continued. The motion on the table was this: "This House believes that Arab revolutions will just produce different dictators." In the debate, I took the opposite position of the motion, arguing that the information revolution has ushered in a new era of public empowerment that is difficult for rulers to reverse. A large Tunisian audience was polled at the end of the debate on whether they agreed with the pessimistic motion. A majority opposed the motion, reflecting a sense of optimism that was sensed well beyond Tunisia’s borders. That Tunisia today is the place where the public is especially pessimistic about the direction of the country – where 75% of those polled say the country is on the wrong track – is very telling indeed. And not in a good way.